Financial returns for pig producers are low across Europe and are forcing many businesses to consider their future. The situation is particularly bad in The Netherlands, where figures suggest the number of pig farms will fall by about 8% this year, and as

Jos Thelosen reports, that’s in a country that has already lost half of its producers in the past decade.

The lack of business succession and the high investment required for too limited an income are the main reasons for the decline in the number of Dutch pig producers. Figures from the country’s National Central Bureau for Statistics (CBS) also show that in 2014, 72% of pig farmers aged 50 or more had no successor to take over the business. These days, there are few eager young pig farmers willing to take over from their parents.

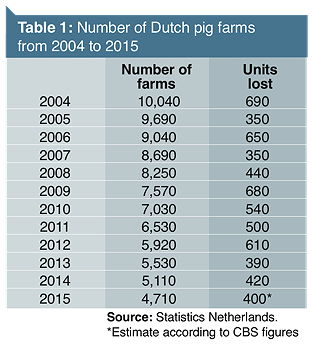

The declining number of pig farms in The Netherlands is a trend that began decades ago. The percentage of producers leaving the industry annually fluctuates between 5% and 9% of the number of pig farms, and according to CBS, almost half of the more than 10,000 businesses keeping pigs in 2004 had exited the sector by 2014 (see Table 1) – that’s an average of 500 businesses each year no longer keeping pigs.

Compounding the problem for those leaving the industry is the fact that pig farms offered for sale are proving hard to sell. According to Arjan van Heerebeek of estate agency ZLTO Vastgoed, the supply is many times greater than the number of buyers.

“Actually, there’s currently no market,” he said. “Only large pig units or locations with potential to develop a business are still finding buyers. Those buyers would tend to be entrepreneurs who market their pigs well, but in the current extremely difficult period, even they have put buying somewhat on hold.”

This picture of a very difficult market for pig farms is confirmed by estate agent Ard Klijsen, of Klijsen Makelaardij, who’s chairman of the Agriculture & Rural Real Estate section of the Dutch Association of Real Estate Agents, Appraisers and Real Estate Experts (NVM).

“The marketability of pig farms has long been under pressure due to the high investment needed in animal welfare and the environment since 2013,” he said. “In 2008 there were only 20 pig businesses for sale across all NVM’s offices in The Netherlands, compared to 106 at the peak in 2012 (the year before new environmental and welfare legislation came into force). At the moment, we have 78 pig farms in our sales portfolio, including four that aren’t publicly listed.”

The financial position of many Dutch pig farms is currently weak and profits are low to negative. The miserable financial situation is due to low selling prices, with bacon pigs averaging 98p/kg and weaners selling at £22/head. The high cost of removing pig muck, at £14/t, makes the situation even more acute.

Where farms are selling is in circumstances where the banks are brokering deals for customers that have viable pig units, but who’re experiencing financial difficulties. Like NVM and ZLTO Vastgoed, the banks have entrepreneurs in their networks who want to invest in pig businesses, and they will approach them directly. This results in so-called “silent sales” of pig farms, and the prices achieved often remain undisclosed.

While the banks are brokering, most farms on the open market are remaining unsold.

“Buyers are scarce,” Arjan van Heerebeek said. “Some large and well-equipped pig farms have changed hands, but at low prices because of the difficult financial situation.”

And, according to Ard Klijsen, there’s been little interest in pig farms since the beginning of last year: “Since then, sales have almost completely stalled.”