Glässer’s disease (GD) is an example of a health problem that’s actually become more widespread and damaging in recent years. Here, Dr Dan Tucker of the University of Cambridge considers GD and why has it become more of an issue

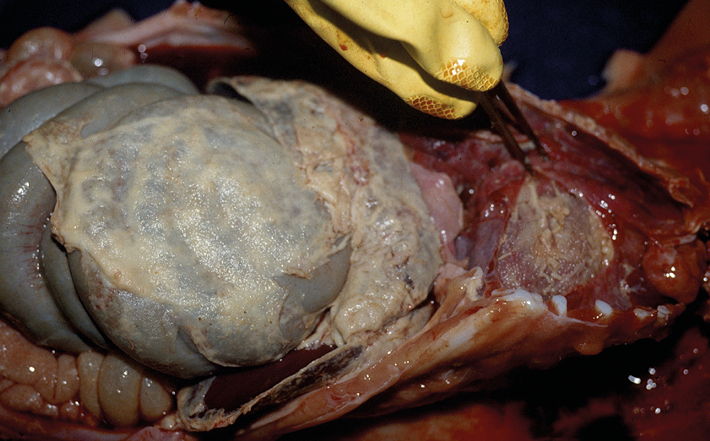

Caused by the bacterium Haemophilus parasuis (HPS), the clinical signs of GD are reduced appetite, depression, arthritis (lameness,) peritonitis (abdominal pain and scrotal swelling) and meningitis.

In acute cases, the first signs may be sudden deaths. The introduction of modern production systems has seen larger outbreaks of GD with increased mortality occurring at almost any stage of production – even including breeding animals. GD can also contribute to other respiratory diseases on a unit, for example by worsening the consequences of enzootic pneumonia. Chronic GD often follows an acute outbreak, with affected batches showing widespread lameness, poor growth and coughing.

Producers need to be concerned about GD because the economic impact is significant. It’s estimated that acute GD, together with the chronic consequences, could cost up to £5/pig at batch level.

Risk factors

Piglets actually become colonised with HPS at a very early stage in life, either from the sow during suckling or from litter-mates in the first few weeks of life. Under normal, healthy, circumstances, the suckling pigs all become colonised with HPS while under protection of the sows’ milk-derived antibodies.

Gradually, the piglets develop their own active immune protection against colonisation of their upper airways with HPS so that, by the time the milk-derived sow antibodies have declined after weaning, they’re fully and actively protected. Outbreaks of GD occur where there’s a failure in this balance between natural colonisation and immunity.

A three-pronged approach can help minimise the losses associated with an outbreak of GD. First, a thorough veterinary diagnostic investigation is needed to rule out other diseases that may have a similar appearance to GD. These can include nutritional deficiencies such as Mulberry Heart disease, or other infections including Salmonella and Streptococcus suis. Confirmation of GD is achieved by growing the HPS organism from the affected tissues of recently dead pigs.

The second step involves rapid group-level antibiotic treatment of the affected and in-contact pigs. Recent studies in the UK show that HPS remains susceptible to a wide range of antibiotics. Although in-feed and in-water medication using penicillin-based products can have labour-saving attractions, there are limitations to these methods including delays to introducing therapy and ensuring all pigs take in a sufficient dose. Individual injection with single-dose, prolonged-duration antibiotic products is a more certain way of ensuring that all sick and susceptible animals have sustained therapy with a rapid onset.

The third response to an outbreak of GD is to use vaccination to build immunity at herd level. Bearing in mind that immunity against HPS can be strain specific, it is important to select a vaccine that gives the broadest range of protection possible. One product, Suvaxyn M hyo-Parasuis (Zoetis), gives protection against two widespread virulent strains of HPS – serotypes 4 and 5.

Vaccination can be introduced from seven days of age, with a second dose two to three weeks later. However, in the face of an acute outbreak of GD, older pigs can be vaccinated providing the onset of immunity can be achieved before the age of expected challenge.

Preventive plan

Although vaccination is a crucial component of any preventive programme for GD, it’s always worthwhile reviewing management-based steps since these can also make a significant contribution. Managing the sow herd to ensure the quantity, quality and accessibility of colostrum is a key step – consider the parity structure, acclimatisation, optimum body condition at farrowing, feed management and so on.

At weaning, avoid segregation from the sows too early (for example less than 21 days), and take steps to avoid mixing of piglets from different breeding sources. At all stages of production, ensure steps are taken to minimise environmental stress. Finally, always plan new stock introductions carefully, being sure to obtain data on the known health status of the source unit, with planning for robust isolation and acclimatisation programmes, in particular where high-value replacement breeding stock are to be introduced.

GD is likely to remain present in the industry for the long-term. However, by remaining vigilant for clinical signs, taking rapid steps to confirm its presence and to implement proven control and prevention measures, it’s possible to reduce the impact of this significant challenge.

Risk situations for Glässer’s disease

Early weaning: This can result in incomplete colonisation by HPS from the sow before the decline of protective milk-based immunity. Pigs have not developed active immunity and are highly vulnerable to GD when they meet HPS after weaning.

Multi-sourced weaner grow-outs: Different breeding herds have different strains of HPS in the sows. Immunity to HPS is strain specific and outbreaks of GD occur where different sources of piglets are mixed at weaning, allowing exchange of new HPS strains to occur before active immunity has developed.

Outbreaks following introduction of new stock: The worst cases of GD occur where new ‘hot’ strains of HPS arrive with bought-in replacement breeders, with rapid spread through the susceptible herd.

Sporadic deaths in bought-in boars and gilts: Here the newly arrived, immunologically naïve pigs meet the local hot strains of HPS resulting in severe disease.