Pig World editor Graeme Kirk visits a European farrow-to-finish unit that’s using the boar taint vaccine Improvac and wouldn’t consider moving back to surgical castration

As far as Belgian pig producers Luc and Monique Stinkens are concerned, there’s no downside to using Zoetis’ boar taint vaccine, Improvac. Not only are their finishers classifying better at the abattoir, but they eat less because they’re so much more efficient converters of feedstuffs than castrates. They’ve also been able to cut antibiotic use.

“It’s a much better thing to do,” Monique says. “It’s a decision we made from the heart, and we took it because we thought it was right.

“Castration was time-consuming and endangered the pigs’ health,” she adds. “And we’ve been able to cut down on antibiotics use as a result, which fits in nicely with our Government’s plans to reduce antimicrobial use.”

The couple run 310 Topigs 20 sows on an indoor weekly batch system based near Grote-Brogel in north-east Belgium. They inseminate with an elite Belgian Pietrain sire line, and aim to finish their pigs at a deadweight of 83kg. All their production goes to the Belgian supermarket chain Colruyt, which stopped selling pork from castrates in 2010. In fact, it now only takes meat from gilts or Improvac-treated boars after consumer trials showed this produced the best pork.

The farm features in a video that runs on screens above the supermarket’s meat shelves and shows and describes the production system. Unusually for the Continent, the gestating sows are loose housed on straw. And possibly even more unusually, they get classical music played to them through a system of speakers; something Monique is convinced helps keep them calm.

The sow shed was built in 2006, and features electronic sow feeders. These are also used to separate the sows ready to move to the farrowing rooms.

The farrowing set-up is much less hi-tech in that each room, which hold 12 crates, has a manual feeding system to ensure the sows are fed to appetite and can be closely monitored. Another interesting feature here is that there’s a piglet safety system that means the floor drops when the sow stands up – rather than the sow bed rising – to reduce the risk of piglets getting crushed.

That said, piglet mortality on the unit still runs at 16%, with the averages showing 15 born alive from each litter and an output of 30 pigs/sow/year. Barring any breeding failures or health problems, the sows are culled after eight litters.

Weaning takes place at 23/24 days, and the sows are moved to service crates where they’re confined for a further week before heading back to the straw yards.

Minimum mixing

The weaned piglets move to small grower pens, and as far as possible are kept with their littermates, with mixing kept to a minimum. The boars get their first Improvac injection at between 10 and 12 weeks of age. This is a 2ml dose given intramuscularly by Luc using a specially designed system to keep the process as safe as possible. The needle is protected to prevent the operator being injected by accident, and the dosing gun needs to be applied as straight as possible to operate correctly. To make this process as straightforward as possible, the boars and gilts get different colours of ear tags so they can be easily distinguished.

A second 2ml dose of Improvac is required at about 20 weeks to keep boar taint and sexual behaviour at bay as the vaccine isn’t permanent and will wear off in time.

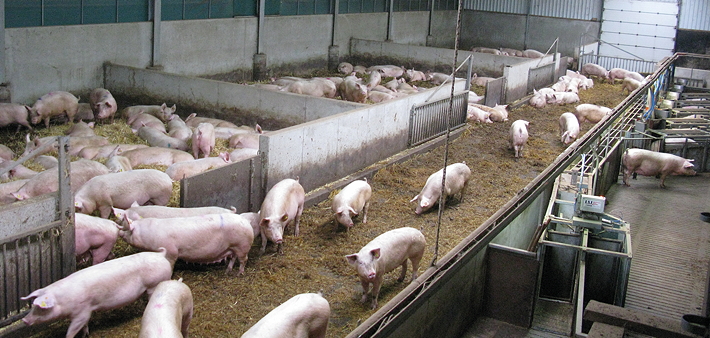

At Monique and Luc’s farm, the pigs are moved to one of four large finishing rooms that each hold 275 pigs. An Optisort system, that uses a camera to estimate each pig’s weight, is used to both divert the pigs to a choice of finisher diets when necessary, and will also filter the pigs that are ready to go into a separate pen ready for loading for the abattoir.

Despite such a large number of pigs being kept together, the finishing rooms are very quiet because there’s none of the riding normally associated with boars and gilts being housed together. Clearly this is also a great benefit as the injuries that can occur from such behaviour can be very costly.

No going back

As far as Monique is concerned, she wouldn’t go back to surgical castration, although she also acknowledges that entires are unsaleable in many markets.

“As far as I’m concerned, surgical castration is not needed,” she says. “There are people who say it should be allowed to continue because there’s no alternative, but they’re lying to the public – it’s a practice that’s no longer acceptable.”

* * * * *

Improvac’s mode of action

Improvac isn’t a hormone and has no direct hormonal or drug activity. The European Medicines Agency states “Improvac is an immunological product, which has a mode of action similar to that of a vaccine”. This is because it stimulates the pig’s immune system to produce antibodies that ultimately block and reverse the accumulation of androstenone and skatole, the compounds responsible for boar taint.

The antigen in Improvac is a synthetic, incomplete analogue of gonadotropin-releasing factor (GnRF) linked to a carrier protein to make it immunogenic; that is, to help trigger the immunological response. The combination is slightly different to natural GnRF and thus triggers antibodies that neutralise the natural GnRF. The difference also means that it has no hormonal activity. The carrier protein is one that’s used widely in many human vaccines.

Improvac has no direct effect in eliminating boar taint. Instead, it inhibits testicular activity, preventing the production of androstenone, and also allows the liver to more effectively metabolise and eliminate skatole.

The first dose of Improvac that’s administered at about 10 weeks of age (minimum eight weeks) has no effect on testicular function or on boar taint; it simply “primes” the pig’s immune system so that it’s ready to respond quickly to the second dose that’s given at about 20-weeks old (four-to-six weeks before slaughter, and a minimum of four weeks after the first dose). It then takes another four-to-six weeks for the androstenone and skatole to be eliminated from the boar.