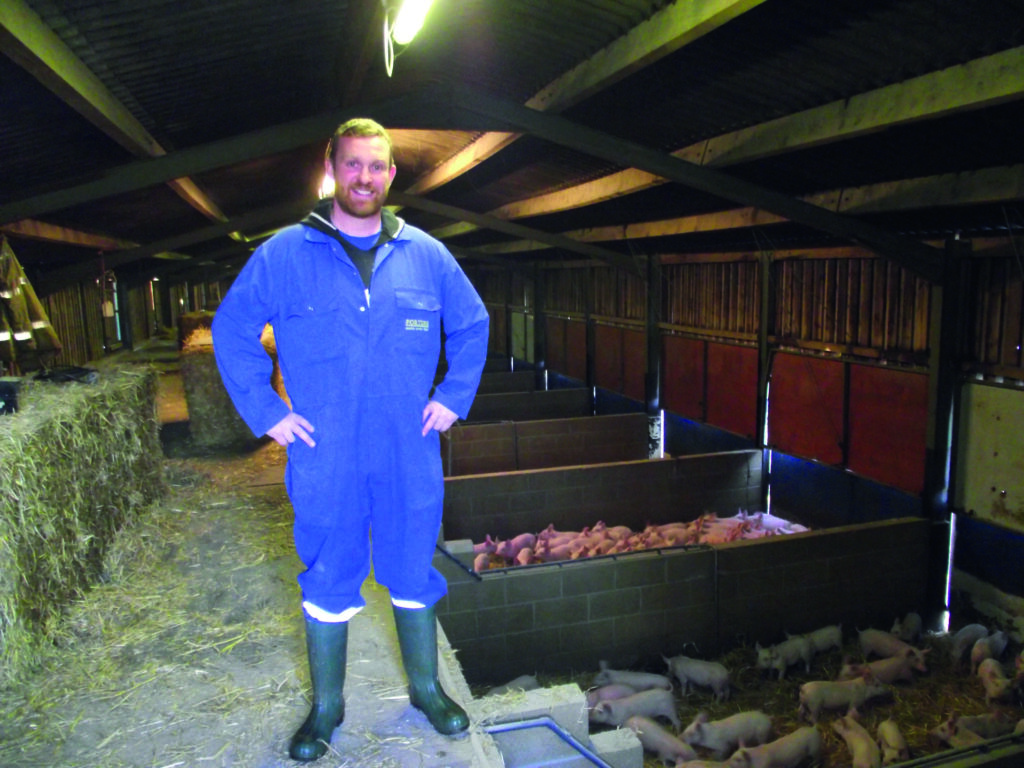

It’s four years since Gareth Virgo joined JE Porter, and fuelled by his dedication, drive and a determination to do the ‘basics best’, the 620-sow breed-to-finish operation has subsequently thrived to achieve outstanding results.

Gareth, the 2016 National Pig Awards Unit Manager of the Year, is modest, but his aspiration to build a herd capable of achieving its genetic potential has turned this Lincolnshire business around.

The unit staff and his employer, Graham Porter, have been inspired by his passion.

Porters, a family-owned farming company, employs 55 staff, cultivates 3,000 arable acres, mills 5,000 tonnes of feed a week and produces around 8 million broilers and more than 17,000 pigs a year. Pig farming has been part of this operation since 1968.

The closed herd produces lean, high-conformation slaughter progeny and sells 300 pigs a week at 90 kgs (lwt) to Woodheads, with a further 100, at 60 to 120 kgs, through a local wholesaler. Current performance shows an average daily gain (ADG) of 900 to 1,000 grams for growing and finishing pigs, with a feed conversion ratio (FCR) of 2.3. And with sow productivity booming, more finishers are now being sold to independent butchers, specialist retail outlets and for hog roasts.

“There is a strong market for this kind of pig production with good opportunities for efficient herds,” said Gareth.

Pigs are on straw throughout their lives. It’s labour intensive, but the staff don’t baulk at mucking out. “It’s a time when you can observe your pigs as individuals,” said Craig Brown, farrowing house assistant manager.

Although the business is founded on good health and proven genetics, the herd’s outstanding results are due to good stockmanship, Gareth said.

Welfare-oriented systems, such as this one, rely on a high level of technical aptitude. Gareth believes the lack of skilled, motivated staff in the UK pig sector will limit market share.

“If this industry can’t find capable, skilled technicians and reward them so they stay, then it won’t be able to build on its current success with high welfare pork,” he added.

Productive principles

Gareth’s principal aim has been to drive sow productivity. Conception rates have improved significantly since he joined the team in 2012.

The herd average was 74.1 per cent – it’s now 93 per cent. Gilt conception was 65.3 per cent and is currently 95.5 per cent, while empty days are now down to 9.9 days per sow. Proactive culling, good oestrus detection and improvements to semen quality have been instrumental in driving better results.

“We collect our own AI and I’ve invested in our lab and semen preparation. I took advice from Bob Gornall of Rotech/Schippers and Paul Ibbotson of Flawborough Pig Services, and focused on improving hygiene and temperature control. We’ve standardised semen processing to reduce contamination risks, and installing a water filtration unit has improved water quality, and helped boost numbers born,” said Gareth.

Litter size has responded positively, too. Sows are now weaning 29.31 pigs on a 12-month average and achieved 30.8 during the summer. Unfortunately, pre-weaning mortality has increased from 10 per cent to 11.9 per cent. A re-assessment of farrowing management has included a move to chopped straw, which is easier for piglets to walk over. Craig is also providing additional creep lamps behind sows as they farrow and is considering heated mats.

Stringent selection

With sow productivity now on track, the herd’s 50 per cent replacement rate and its population of GGPs and GPs are under review.

“Having a large gilt pool has allowed me to get the quality standard I want in my GPs and F1s. We’ve advanced genetically and our replacements are now exceptional, but we’re still keeping proven females up to parity 8, which needs attention.

“Reducing the proportion of damline-derived progeny in the finishing herd would also offer opportunities to improve efficiency,” Craig added

The Rattlerow genetics produce plenty of easy-to-manage progeny, with born alive numbers up by three pigs per litter during the past two years. Sows now have an average 14 live births/farrowing, while gilts yield 13.2.

All lactating females are fed an energy-rich ration individually, to promote milk production and control weight loss. The dry sow diet has a lower digestible energy (DE) level, and is balanced to support body condition and promote foetal development.

Only cereal-based ingredients that meet defined quality standards are used, and manufacturing mirrors the purity of a home mill and mixing process, helping ensure diets are of a consistently good quality.

Herd health. Profiles and surveillance – key constituents for effective disease management

A number of well-established vaccination programmes are used on the unit, although rising productivity has created pressure points, and PRRS, EP and APP control strategies have been reviewed in the last two years.

Gemma Thwaites, of the Garth Pig Practice, has worked with Gareth and his team to establish a clinical herd profile. She implemented whole-herd clinical investigations to find out what pathogens were circulating and when.

Rigorous blood sampling, using ELISA and PCR tests provided by MSD Animal Health’s Vetcheck and Respicheck services, confirmed that PRRS was circulating throughout the herd. It was particularly active from two to three weeks post-weaning and was interacting with other disease issues to weaken pigs’ immunity.

“We were confident no new diseases had arrived here. It was more that the situation had evolved and the control strategies in place were just not providing enough protection,” Gemma said.

Once the maternal PRRS sow vaccination waned, pigs became vulnerable, and consequently more susceptible, to other disease challenges. Gareth felt the rearing herd was being held back and abattoir reports also indicated some APP challenge.

So, a PRRS piglet vaccination programme, using MSD Animal Health’s Porcilis PRRS vaccine, was introduced at two to three weeks of age. To minimise stress, Gareth also chose to use the needle-free IDAL intradermal (ID) vaccination system.

“We’ve successfully cut out one intervention at weaning by using the combined Porcilis PCV MHyo vaccine for EP and PCV2, so we didn’t want to add another jab at weaning. But previous experience with PRRS vaccination at two weeks of age had shown me it could be tough on young piglets. You really want to minimise stress when you’re dealing with this virus, so a needle-free approach seemed sensible,” he said.

Vet Gemma agreed that needleless vaccination has key advantages, as the virulent PRRS virus can be easily transferred though tissue and body fluids.

“Even when needles are changed between litters, the risk of spreading this disease can still exist. Injecting one viraemic piglet, then subsequently injecting its litter mates, can readily transfer infection. These carrier pigs can then go on to become reservoirs of infection, capable of mounting a perpetual challenge to your herd. Intradermal vaccination is non-invasive and eliminates such risks,” she added.

Simplicity and stability

The IDAL system is also stockman and pig-friendly, said Craig, as it offers considerable time savings, when compared with conventional injecting methods. It’s easy to use, less stressful for the piglets and safer than using hypodermics. The gun also logs the number of doses administered – valid data that is simply transferred to the medicine book.

Achieving a stable status is the key to controlling PRRS, and once it’s under control, other health issues often improve.

By building a clinical profile, the business has identified the disease complexes in its herd, what influences activity and when pigs are most vulnerable to infection.

This has helped Gareth break the infection cycle and build herd immunity through strategic vaccination programmes.

Regular blood tests and serology confirm that PRRS is now under control. There are fewer sick pigs, the number of medications and interventions has fallen, production has become more uniform and no pleurisy (APP) has been reported in abattoir data for months.

Going forward, disease surveillance will continue with blood samples taken every three months, then every six to nine months, providing there are no disease indications or outbreaks. Long-term, the aim is to carry out a whole-herd clinical evaluation every year, supported by frequent, random saliva samples.