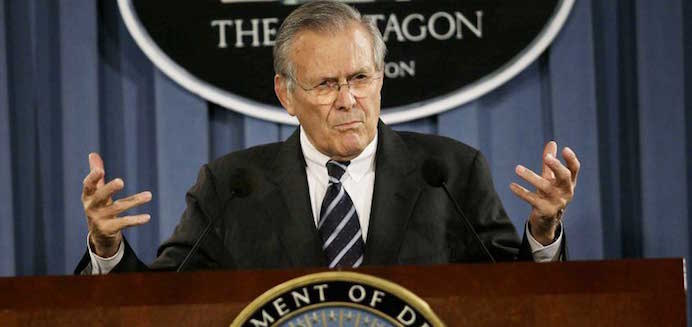

Never has Donald Rumsfeld’s legendary summary of our limited understanding of an uncertain world been more apt.

As the then US Secretary of State for Defence said: “There are known knowns. There are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we now know we don’t know.”

With Brexit negotiations finally under way, it is fair to say the ‘known unknowns’ outnumber the ‘knowns’ by a fair margin. Take, for example, the pig sector’s two biggest concerns about post-Brexit trade – the threat of lower standard imports and EU access.

Some of our potential future trading partners operate very different farming systems, with very different values, to ours. Farming Minister George Eustice has quite rightly highlighted, for example, the contrast between the ‘low-cost’ US approach and the UK’s emphasis on provenance, welfare and food safety.

The Brazilian meat scandal, engulfing some of the biggest meat exporters in the world, has indicated the differences in some cases are even greater than we ever imagined.

Prime Minister Theresa May and Defra ministers have been at pains, whenever questioned on the issue, to insist the Government will not allow the UK’s high health and welfare standards to be compromised in any new trade deal.

And yet the reality, as Mr Eustice acknowledged under close questioning from EFRA chair Neil Parish, is that we are likely to be powerless, legally, under WTO rules, to exclude imports on the basis of welfare standards alone. The Farming Minister highlighted the role consumers could play in resisting lower standards.

But in the cold political reality, will consumer power trump a Trump-driven US trade deal with so many other interests at stake? We may well be restricted to trying to manage and mitigate low-cost, lower standard imports, rather than trying to stop them.

And what of access to the EU market? Of course we want free access with zero tariff and non-tariff barriers. Why wouldn’t we?

It is absolutely right that this should be the starting point for our trade negotiations with the remaining 27 member states.

But we also want control over immigration and regulation. Among those 27 member states will be plenty with reasons not to grant us this ‘best-of-all-worlds’ approach.

We might well end up, as major negotiations like this tend to, with a deal full of compromises forged at the 11th hour. Or we might leave with no deal, an outcome Brexit Secretary David Davis acknowledged would be bad for everyone, including farmers, who would face tariffs of ‘30-40%’ on exports to the EU. Equally worryingly, he signalled that the Government had not yet studied the economic impact of a ‘no deal’.

Where will it all end? Nobody knows.