African swine fever (ASF) looms large over the EU pig farming sector as a clear and present danger.

So far it has affected the fringes of the EU pig industry but is now too close for comfort to its heartland. Denmark’s plans for a 44-mile fence along its German border to keep wild boar out highlight the current nervousness.

The official risk status of incursion to the UK remains ‘low’. But, as the NPA points out, this does not take into account the devastation that would be wreaked if the virus did reach these shores. What makes the situation particularly worthy of attention is that, as with foot-and-mouth in 2001 and classical swine fever (CSF) in 2000, it only takes a single incident to bring the industry to a standstill. And that is likely to be down to human error.

“I invite, once again, all member states free from African swine fever, to scale up their preventive measures in line with the EU strategy,” EU health & food safety commissioner Vytenis Andriukaitis told EU ministers in February, stressing, ‘once again, the crucial importance of the human factor’.

What is ASF?

ASF is a highly contagious viral disease of pigs, warthogs, European wild boar and American wild pigs.

The clinical signs include:

- Fever

- Loss of appetite

- Lack of energy

- Sudden death with few signs beforehand

- Vomiting and diarrhoea

- Red or dark skin on the ears and snout

- Swollen red eyes

- Laboured breathing and coughing

- Abortions, stillbirths and weak litters

- Weakness.

There are several different strains. Severe strains are generally fatal, with mortality rates as high as 100%. It doesn’t affect humans and there is no vaccine.

The virus can be spread by:

- Pigs eating infectious meat or meat products

- Contact with infected pigs or wild boar or their faeces or body fluids

- Contact with anything contaminated with the virus, including people and their clothing and vehicles and other equipment.

The history of ASF

ASF was first documented in Kenya in 1921, but was retrospectively identified as having affected pigs as far back as 1906, according to an article in Veterinary Pathology.

It remained restricted to Africa until it was discovered in Portugal in 1957, causing nearly 100% mortality. The virus made its way into various other countries beyond Africa in the 1970s and ’80s, but was eradicated from all of them, except Sardinia, where it remains.

Then in 2007, the virus arrived in Georgia, probably via the port of Poti in ship waste containing contaminated pork products disposed of in local dumps. Molecular analysis linked the strain to Madagascar.

This was the furthest north it had ever been discovered – and from that moment its spread in wild boar, backyard pigs and commercial farms across Europe has been relentless.

Within two months, 52 of Georgia’s 65 districts had been affected and more than 30,000 pigs had died. Neighbouring Armenia, Azerbaijan, and then Russia, in November 2007, were soon affected. Ukraine recorded its first outbreak in 2012, followed by Belarus (2013), and – marking its entry into the EU – Lithuania, Poland and Latvia (all 2014) and Estonia (2015). Moldova followed in 2016.

Russian perspective

An estimated two million pigs have been killed in Russia alone as a result of ASF. Sergey Yushin, chairman of Russia’s National Meat Association, told Pig World the disease had been allowed to spread out of control because the Russian Federal Government and the veterinary authorities had initially underestimated the problem.

Wild animals have been the main cause of ASF’s spread. Yet, even recently, plans to cull wild boar in Russia were thwarted by animal welfare campaigners, he said.

Wild animals have been the main cause of ASF’s spread. Yet, even recently, plans to cull wild boar in Russia were thwarted by animal welfare campaigners, he said.

The virus is proving very costly. Large commercial pig farms, up to 6,000 sows, can be forced to spend $1 million on ‘unprecedented and extremely expensive measures to keep the disease out,’ for example on high fences and disinfection posts, Mr Yushin said.

They are also buying up pig populations from backyard farmers, with a promise they will never breed pigs again, while workers are being paid more to remain on farms for at least two weeks as a bioscurity measure. Farmers are also paying hunters to kill wild boar.

This is on top of the blow it is dealing to Russia’s export plans. For years, ASF was largely contained in its European regions, prompting big pork companies to invest further east with a view to securing regionalised exports to the likes of China and Japan. That plan appears to have been thwarted after the virus made its way thousands of miles east into Siberia in 2017.

Last year, it also gained a foothold in Belgorod Oblast – Russia’s densest pig area – in the west of the country, hitting large commercial farms owned by the country’s biggest pig producer Miratorg. A few weeks ago, 10,000 pigs were culled in Kaliningrad Oblast, another part of the Russian Federation.

Rapid EU spread in 2017

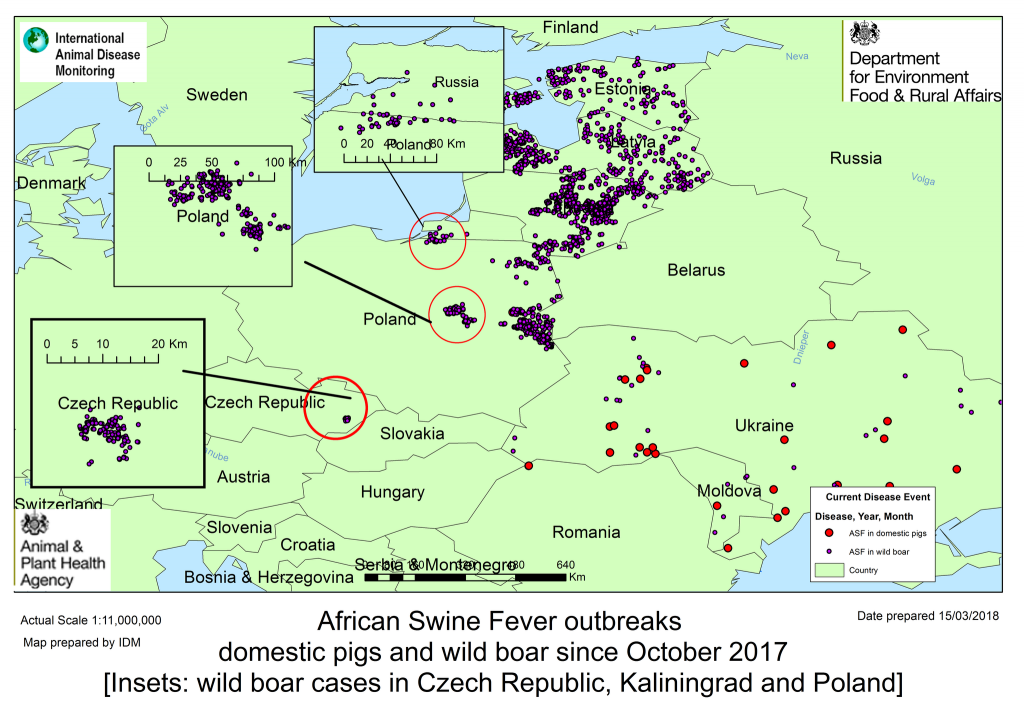

In June ASF made a big geographic leap into the Czech Republic for the first time, where it was found in wild boar. Soon after, Romania’s first case was discovered in backyard pigs near an infected part of Ukraine.

In June ASF made a big geographic leap into the Czech Republic for the first time, where it was found in wild boar. Soon after, Romania’s first case was discovered in backyard pigs near an infected part of Ukraine.

In the autumn Poland recorded cases in wild boar near Warsaw, 100km further west than previously. This is of particular concern, according to the Animal Plant and Health Agency (APHA), because of the high density of domestic pig production in north-west Poland and the proximity to the pig industry in neighbouring Germany and Denmark.

In February, Polish farm leaders said ASF had already ruined ‘thousands of farms’. From January to March 2018 local vets registered 511 infected wild boars, compared with 741 in all of 2017, including 388 cases reported in the last quarter. This data suggests the flow of infected wild boar coming to Poland is growing fast and it is causing new outbreaks among domestic pigs.

Taken together with the Russian situation and new outbreaks in Lithuania, this ‘signifies a spread in geographic distribution of ASF, a possible drop in biosecurity awareness and therefore a further increase in the weight of infection in East Europe’, APHA said.

Generally, these jumps have arisen because wild boar have been illegally fed contaminated meat, it added. Polish farmers were blamed, for example, for grazing cattle in areas where wild boar had access.

Worryingly, there is evidence that some wild boar have tested positive for antibodies, suggesting they survive initial infection and may be acting as a reservoir host.

Much of what has happened tallies with modelling by Russian veterinary body Rosselkhoznadzor, which estimated that ASF was travelling at an average speed of 20km per month, east and west. This would see western Europe becoming vulnerable in the not-too-distant future.

EU containment measures

The EU has laid down prevention and control measures that regionalise areas where ASF is suspected or confirmed on holdings or in wild boar. Measures in place to control ASF within the EU include:

- Restricted ASF areas preventing movement of pigs and pork products outside infected areas. This includes border checks.

- Wild boar culling and safe disposal of dead wild boar carcases, which are tested for ASF. Feeding of wild boar is banned in some places.

- Enhanced wild boar surveillance for ASF in EU countries bordering Ukraine, Russia and Belarus.

- Moves to prevent spill-over of infection into domestic pigs.

- Increased awareness of pig keepers of the signs of ASF and more rapid detection and removal of infected pigs.

The Commission is providing financial and other support in some areas, including managing wild boar populations, awareness campaigns, surveillance, veterinary advice and research in diagnostics and the development of a vaccine. It has also provided funding for small farmers in infected areas of Poland on the condition they stay out of pig production.

Affected member states often adopt additional measures. Current evidence indicates that the Czech Republic has contained its outbreak in wild boar using a combination of strict measures, including fencing off a 40sq.km high risk zone, intense wild boar culling and testing within and outside this zone, and heightened biosecurity.

Denmark’s plans for a fence and wild boar culling hit the headlines last week. Although no cases of ASF have yet been detected in Denmark, the country’s Minister for Food and the Environment Esben Lunde Larsen said the country did not want to take any risks.

“If African swine fever virus broke out in Denmark, all exports to third countries would immediately stop,” Mr Larsen said. Denmark’s pig exports amount to 33 billion Danish krone (£3.85bn) per year. An outbreak of the disease in Denmark would shut down the entire industry.

Poland plans to build a 1,200-km fence, costing around £48 million, on its border with Russia, Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania to protect it against wild boar. It wants EU funding but the Commission is reportedly not keen, fearing it will do little to stem the flow of wild boar across the border. In Russia, wild boar have been know to enter farms by burrowing under fences.

‘Not out of control’

In his February address to EU Ministers, Mr Andriukaitis refuted suggestions ASF was ‘out of control’, pointing out that, thanks to the EU’s regionalised and regularly updated ASF programme, it has ‘advanced less than few hundred kilometres in four years’. This compares favourably with the spread witnessed in countries to the east, he added.

Calling for an ‘interdisciplinary collaborative approach to combatting and preventing ASF in the EU’, he stressed ‘the seriousness that the Commission attaches to the threat of ASF’.

The recent public pronouncements and actions seen in countries like Denmark and Poland in recent weeks suggest that, despite his assurances, concern over the virus is growing across much of the continent.

Additional reporting by Vladislav Vorotnikov