Commercial pig production is all about efficiencies – and building design plays a key role in bringing together incremental gains, which can add up to huge savings. Olivia Cooper visited Stephen Tuer Farms in Yorkshire to find out more

Maximising pork production from the sow to the finished pig takes great attention to detail at every stage. You need the right genetics, the right feed and the right management. But underpinning everything is the environment: temperature, air quality, cleanliness, space, light and the ability to express natural behaviour.

If you get the building design wrong, pig health, welfare and productivity will suffer. Get it right and you will have happy, healthy, productive pigs and optimum labour efficiencies.

Steve Tuer keeps 1,200 sows at Hutton Grange, Northallerton, from which he breeds and finishes 600 pigs a week. He keeps a close eye on the latest products – and is steadily replacing pig buildings to allow for continued improvement and expansion.

The farm is split into two units – one for farrowing and the other for finishing. Recent investments include new farrowing and dry sow accommodation in 2015; a 1,600-place nursery building in 2016 and a 2,000-place finishing house in 2017.

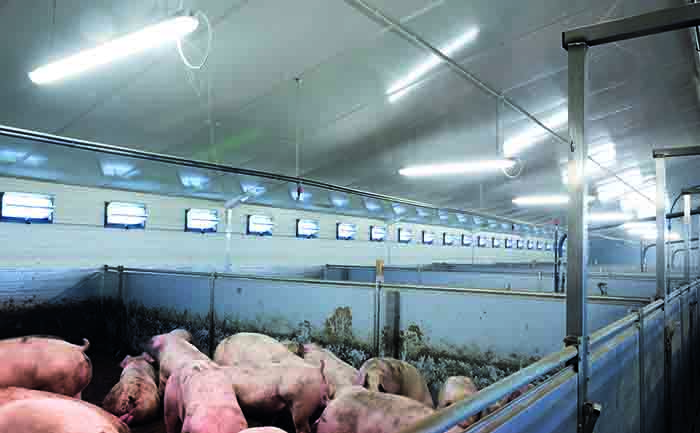

All the pigs – bar dry sows – are housed on slats, with forced insulation using fans and louvred inlets in the walls. “Because of this there are only a few different ways you can design the building,” said Mr Tuer.

But he knew what he wanted and enlisted the expertise of IDS Pigs to build the most recent finishing house. “We wanted five rooms and slatted floors. We also wanted a Skov ventilation system, insulated walls and roof, and washable fixtures and fittings.”

The new steel-framed building is 120m x 14m with the eaves at 2.4m and a 15-degree roof pitch. It has insulated panel walls and a fibre cement roof, with fans running along the length of the building in the roofline. These create negative pressure in the building, bringing fresh air in through louvred windows, with the whole system controlled by computer.

“We have thermostats in the building and temperature sensors outside, and programme the computer according to pig numbers and weight – it then calculates the minimum and optimal ventilation level,” said Mr Tuer.

With slatted floors, it’s essential that buildings are well insulated, to keep the pigs warm in the winter and cool in the summer – as well as reducing heating costs. “It amazes me that people are still building pig housing without insulation – I think it’s mad,” Mr Tuer observed.

He opted for Recticel’s polyurethane Cronus insulation in the roof, as it has an extremely high insulation value so is thinner and lighter than other alternatives. It also has a reinforced fibreglass and polyester lining, which means it can be pressure- washed at up to 180 bar.

“Having a building you can wash down thoroughly is vital. The industry is under pressure to reduce antibiotic use, so it’s increasingly important to design buildings with hygiene in mind,” he said.

At turnaround, as each room in the finishing shed is emptied, automatic sprinklers come on, covering everything in hot water. The room is then fully pressure washed, dried and disinfected before the next batch arrives, with the farm’s AD plant used to pre-heat the shed.

Another benefit of the Cronus insulation is that it is white, reflecting light down into the shed, and it sits beneath the purlins, creating a smooth underside to the roof. “You don’t want anything to upset the air flow around the building,” said Mr Tuer.

Air comes in through the windows, rises to the ceiling towards the middle of the room before dropping down to pig height to soak up moisture and heat, rising again to exit through the roof. If that flow is disrupted by purlins, air will drop down in the wrong place, upsetting the dynamics of the shed.

Mr Tuer added: “There is a noticeable improvement in insulation value – all of the dedicated pig buildings have some version of insulation, but it’s gotten better and better over the years. There is definitely less temperature fluctuation in the building with Recticel insulation, even compared to the other new builds. On the coldest days it’s always the warmest building, and on the hottest days it’s always the coolest.”

This has a direct impact on the pigs, too.

“The pigs have better feed intakes in the summer when they’re cooler, and we’ve also got virtually no tail biting.”

Pigs in the new buildings also have far fewer health problems – with less pneumonia and infectious diseases in particular – due to improved ventilation and hygiene, he added.

Mr Tuer feeds all of the pigs a liquid diet of whey, wheat distiller’s syrup and a yeast product, to keep costs down. From his 1,200 acres of arable land he also mixes in home-grown wheat and barley, plus soya, wheat feed and minerals, making up 45% of the ration.

Feed conversion efficiencies are marginally lower than with a solid ration, but cheaper costs mean the finances stack up.

The sows are Large White crossed with Landrace, and Mr Tuer uses a Danish Duroc sire line. He heats the farrowing house to a target temperature of 20 degrees Celsius for birthing, dropping down to 17 degrees Celsius at weaning.

The piglets also have a heated creep area. The nursery shed – heated with warm air blowers from the AD plant – is kept at 28 degrees Celsius when initially stocked with four-week-old weaners, dropping to 25 degrees Celsius. The finishing accommodation starts at 25 degrees Celsius when the pigs are 11-12 weeks old, and is reduced gradually to 20 degrees Celsius as they grow.

“Pigs are very much like people – they are relatively hairless and can’t control their body temperature as well as cattle or sheep, so we have to keep them warm in the winter and cool in the summer,” Mr Tuer said.

He finishes the grown pigs at 88kg deadweight – at around 26 weeks of age – for Karro, on contract through Yorkshire Farmers.

He expects all his buildings to pay for themselves within eight years, through higher productivity and reduced running costs. “In the old buildings, we have much poorer temperature control and feed conversion efficiencies, more heat demand, and more vices. The pigs just don’t do as well,” he said.

With 10 full-time staff and two part-time workers across the whole farm, what’s the next investment for this forward-thinking producer?

“If I could find more staff, I would put in another finishing building – but it’s difficult sourcing and keeping good workers, particularly in light of Brexit.”

But the design would remain much the same as the latest building, bar a few tweaks for ease of labour.

“The staff prefer one gate system over another as it’s easier to use, but I’d do everything else the same,” he added.

It all ties into the farms’ ethos: Using genetics, technology and efficiency to produce the most efficient kg of pig meat possible.

KEY POINTS

- Housing environments underpin whole herd efficiencies

- New, well-designed buildings will improve health and productivity

- Use insulation to keep cool in the summer, warm in winter, and reduce heating costs

- Smooth ceilings improve air flow and ventilation

- Consider ease of cleaning for hygiene and biosecurity