In the December issue of Pig World, renowned industry analyst Mick Sloyan took an in-depth look at recent global pork market trends and explains what this tells us about UK market prospects heading into 2024.

In the December issue of Pig World, renowned industry analyst Mick Sloyan took an in-depth look at recent global pork market trends and explains what this tells us about UK market prospects heading into 2024.

Many things have changed since this country left the EU, but many things have remained the same.

In the pork market, most arrangements were rolled over, including trade protection measures that reflect our higher welfare, environmental and other costs imposed on the industry through legislation.

As a result, virtually all our import requirements come from the EU and hardly anything comes from outside Europe. While we are insulated from the world market, we are not isolated from it. What is happening in Iowa and Mato Grosso is having a direct impact on Catalonia, Brittany, Saxony and, ultimately, the UK.

In the last few months, the market has turned and pig prices in most major markets are in decline. It is sometimes difficult to pinpoint the exact time that this happens, but this year has been the exception.

Declining prices

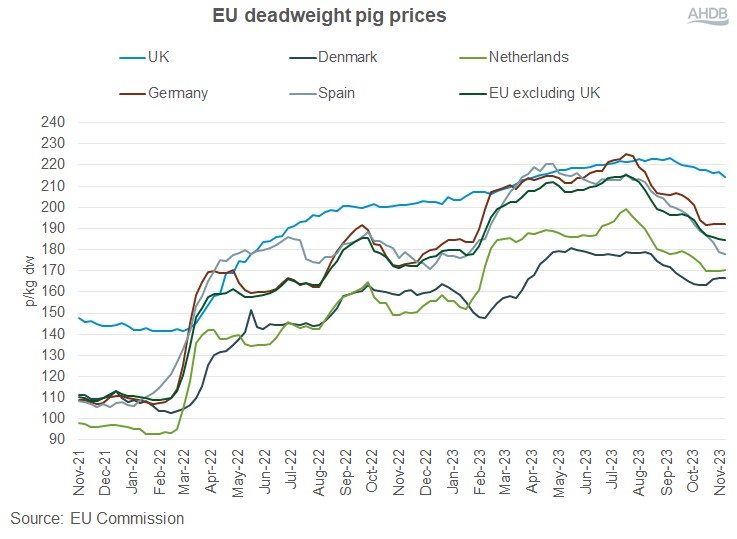

In the middle of July, pig prices reached a peak in Germany, Spain, France and the Netherlands, since when they have been declining steadily. This is perhaps not surprising given how closely linked these markets are, with both live slaughter pigs and pork moving across national borders in very large amounts.

However, average prices in the US and Canada also peaked in mid-July and have since weakened.

The market in Brazil has been relatively weak this year, but it, too, saw a small fall in mid-July, although it has been stable since then.

Market prices in China have also been struggling this year with the recent peak in prices coming a few weeks later in August, since when there has been a steady decline.

This greater alignment of world markets is being influenced through international trade. In recent years, the EU was exporting about one fifth of production to non-EU markets. While the focus in 2019 was on China and Hong Kong as they struggled with ASF, it has looked to diversify exports since then.

By 2022 China/Hong Kong accounted for only 30% of total exports, with the remainder going to a broad range of countries in Asia, Africa and North America.

Spain has been a major player in driving this expansion in exports and now claims to be the second largest pork exporter in the world behind the US.

The US exports about a quarter of its production. Its main markets are closer to home in Mexico and Canada, but it also exports substantial volumes to China/Hong Kong and the rest of Asia, where it competes directly with EU exporters.

Brazil is becoming a more significant player on the world market, with approaching one third of production exported.

As the market in China continues to be volatile, with production recovery leading to very low prices, all the major exporting countries have looked to diversify. This has brought them all into closer competition.

In 2022, prices in North America were strong relative to other exporters. However, in 2023 prices in the Americas trended downwards and, in recent weeks, average market prices in the US, Canada and Brazil were 35-65% lower than the EU average.

The results of this more intense price competition can be seen in export market performance. In 2021, the EU accounted for 41% of global exports. This year, USDA estimates that this will have fallen to 32%.

In contrast, the US has moved from 26% to 30%, while Brazil has gone from 11% to 14% of total global trade.

British market

So, what does all this mean for British pig producers? The British market continues to rely on imports for about half of all the pork and pork products consumed in this country. And all that comes from the EU.

The UK is also the EU’s second largest export market after China. When life gets tougher on global markets, then exporters tend to look closer to home. And as prices fall across the EU, then British wholesalers, retailers and food service companies look to reduce their costs to compete in a market where food inflation continues to outstrip the general rise in the cost of living.

UK exporters are also being directly affected. For example, in September this year, the average value per tonne of frozen pork was 10% lower than a year ago and offal was down by 20%. With lower volumes being exported at lower prices, this has reduced the total value in the market, which will ultimately impact the pig price.

In contrast with many EU countries, pig prices in Great Britain tend to be slower to react. The way in which weekly prices are set in many EU countries lends itself to volatility, especially in the very finely balanced market that we have at present.

For example, in France the national price is determined at a twice weekly virtual auction. In Germany the weekly recommended price is set by a group of farmers cooperatives, and in Spain by a negotiating committee of producers and processors.

However, in this country, the vast majority of pigs are traded on the basis of supply agreements that are linked to some form of pricing formula. The elements that go into the formulae vary widely, but will make some reference to prices in the recent past.

Some supply arrangements also fix prices for longer than a week. While these arrangements don’t stop the market price moving each week, it tends to result in British prices moving up and down more slowly than would be typically seen in the EU.

Challenging outlook

The immediate outlook for British producers looks challenging. US prices are continuing to fall and are fast approaching the equivalent of £1/kg dw, which makes them very price competitive on world markets.

Prices are also very low in China, having dropped below the industry benchmark of 15 RMB (£1.68)/kg. This is having a detrimental impact on global import demand and causing exporters such as Spain to look increasingly at selling more within Europe.

In recent months, a significant gap (as measured by the EU Reference Price) has opened up between British prices and EU prices. At the time of writing, this stood at about 28p/kg dw, which will undoubtedly put considerable pressure on the British market.

There are some signs that the fall in EU prices is slowing, however, and, with the Christmas trade building, there could be some short-term pick in demand. However, the real pressure will come in the New Year.

In the medium term, there is a glimmer of hope, despite a challenging global market for EU exporters. The latest forecast from the USDA indicates that US production will increase in 2024 and that exports will also increase due to higher demand from Canada, the Philippines and South Korea, as well as gaining market share from the EU.

They expect US pig prices to fall in the first half of next year before recovering somewhat in the second half. They are also forecasting that Brazilian production and exports will increase compared to this year.

While all this doesn’t sound very encouraging, their view on the EU is that production will continue to decline in 2024, but that export volumes will stabilise. This seems reasonable, assuming EU prices continue to move back more in line with competitors.

This is already happening in Spain, the EU’s largest exporter, where weekly prices are 50p/kg lower than the peak in July.

The big question is how much further the EU market will fall before it is price competitive enough to sustain a modest volume of exports and stimulate consumption within the EU.

The early months of 2024 will be crucial before, hopefully, the seasonal increase in demand kicks in across Europe in the spring.

The current price differential between Britain and the EU is probably close to a manageable level, especially given very tight supplies. However, further falls in the EU market next year are likely to be reflected eventually in prices in this country.

We all like to keep an eye on the market each week. This used to be a simple matter of looking the SPP. In future, we will all need to take a much broader view of the world.