It is fair to say a far-reaching set of Defra proposals to make the labelling of British food more transparent represent a very mixed bag for the pig sector, including the return of controversial method of production labelling plans. ALISTAIR DRIVER delves into the detail

New Defra proposals aimed at improving transparency and consistency around food labelling would, if implemented, help address one eternal source of frustration for farmers, while, unwittingly, potentially creating a much bigger set of problems.

The 68-page document, launched for consultation by Defra Secretary Steve Barclay in March, backing up a commitment he made at January’s Oxford Farming Conference, lays out a dual-pronged set of proposals.

There are some clear steps to improve country of origin (COO) labelling to help ensure British products produced to higher standards are clearly differentiated against lower standard imports, an aspiration shared by many in the pig sector.

The second part, however, marks the formal return of method of production (MOP) labelling, seen by many as a potential minefield for the pig sector.

Defra dropped plans to consult on a tiered labelling system linked to method of production last year, in response to concerted opposition from within the supply chain over the cost and complexity of the plans and fears they could mislead consumers over welfare claims. But they have now returned with a bang and another tussle likely lies ahead, albeit with the looming General Election adding another layer of uncertainty to the equation.

Mr Barclay said the proposals will ‘ensure greater transparency around the origin of food and methods of production, helping consumers make decisions that align with their values’.

Defra said the proposals also aim to:

- Ensure UK baseline and higher welfare products are accessible, available and affordable.

- Support farmers meeting or exceeding baseline UK welfare regulations by ensuring they are rewarded by the market.

- Improve animal welfare by unlocking untapped market demand for higher welfare products.

Country of Origin proposals

Country of origin information is currently required for all pre-packed food, ‘where its omission would be misleading to consumers’ and for fresh and frozen meat, uncut fresh fruit and vegetables, honey, olive oil and some fish products.

For processed food, it is complicated – where the origin of the primary ingredient is different to that of the food itself and the origin of the food is given, an indication that the origin of the primary ingredient is different must be provided.

But the consultation adds: “Despite these rules, there is a perception that some foods are labelled in a way that is not fully transparent about their origins.”

It gave the example of pigmeat imported into the UK and cured here to produce bacon that can legitimately be labelled as ‘British’ and carry a Union Jack. The labelling rules state that if this bacon is voluntarily declared as British, there must be an additional visible statement that the pork is of a different origin. “However, this may not always be very obvious from the label,” the document states.

And where origin information is mandatory, it can be anywhere on the pack, including on the back in the midst of lots of other information, in a text font that is just 1.2mm high (see the Tesco example on p17).

Defra said it wants to address this situation by exploring ways to make it more obvious to consumers that the pig was reared abroad. It is seeking views on the following options:

- Mandatory origin labelling for ‘minimally processed’ meat products, such as bacon. Over 75% of UK household pork expenditure goes on processed products and minimally processed products, such as sausages, bacon and ham, account for over 90% of all processed pork.

- Increased visibility of origin labelling – the consultation asks for views on requiring additional mandatory origin information on the front of the pack and in larger font sizes than the current minimum of 1.2mm.

- Mandatory origin labelling for certain foods in the out-of-home sector, for example restaurants.

- Greater control of the use of national flags on labels – the consultation asks for views, for example, on whether the written origin of food should be accompanied by a national flag.

While some UK supermarkets already do a good job in differentiating UK from imported products, those who have campaigned for better labelling for a long time believe the proposals could address some of the glaring gaps in retail COO transparency, including the so-called ‘fake farm brands’.

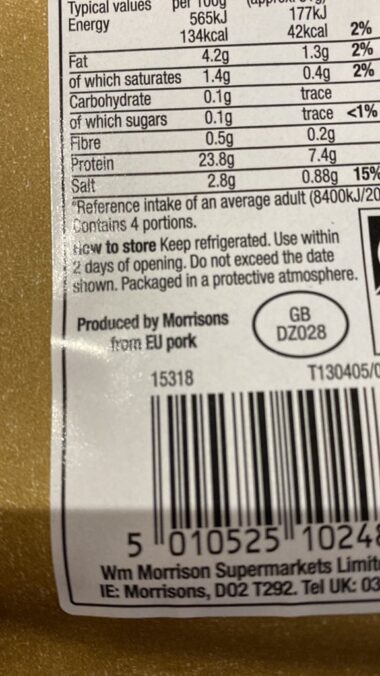

Below is another, more recent example highlighted on ‘X’ in March by Yorkshire pig proudcer Kate Morgan showing ‘Wiltshire cured ham, with no indication of origin on the front but, on the back next to the GB designation, it shows the ham was ‘Produced from EU pork’

Yorkshire producer Anna Longthorp, a key figure behind the #BiteIntoBritish campaign, said: “I want prominent country of origin labelling on the front of a pack so a customer can pick it up, and instantly know where it comes from – without being a detective and searching the fine-print on the back.

“Hopefully, this will address these fake farm names that are designed to dupe consumers into thinking products are British, by making it very clear when they are not.”

Anna also welcomed the prospect of COO labelling on restaurant, pub and café menus. “If they put calories on menus, I don’t see why they can’t put country of origin,” she said.

Method of production labelling

Far more controversial – and potentially much less workable – are the plans for MOP labelling.

The consultation notes that existing regulations on providing information on how animals are reared are ‘limited’ outside of the egg sector. While voluntary labelling initiatives, such as Red Tractor, Quality Meat Scotland and RSPCA Assured, provide some information, ‘they place variable emphasis on animal welfare and do not cover imported products’, the document said.

It also cited ‘strong evidence that consumers find welfare information inaccessible and cite a lack of transparency’, while the voluntary nature of existing labelling means labels use ‘inconsistent, complex language or imagery which may be confusing to, or poorly understood by, consumers, or there is no information at all’.

To address these issues, the consultation sets out proposals to require a mandatory label covering pork, chicken and eggs, chosen because they have the greatest difference in systems of production.

It would apply to all unprocessed pork, chicken and eggs and certain pre-packed and loose minimally processed products with pork, chicken or egg. It would apply to imported products, as well.

How it would work

The proposed label would have five tiers – denoted by, for example, numbers, letters or stars – to differentiate between products that fall below, meet and exceed relevant baseline UK animal welfare regulations.

- The lowest tier would have no specific requirements associated with it, indicating products that are not verified as meeting baseline UK welfare regulations.

- The next tier would indicate products which meet baseline UK welfare regulations.

- The three higher tiers would indicate production standards that increasingly exceed baseline UK welfare regulations.

- All requirements for a tier would need to be met for a product to be labelled as meeting that standard.

The draft standards specify how this could look for pigs:

1) Highest: Free-range

2) High: Outdoor-bred

3) Improved: Enhanced indoor

4) Standard: Indoor (baseline UK welfare regulations)

5) Unclassified: Non-UK standard.

For pigs, the ‘priority metrics’ would be: Stocking density, enrichment, outdoor access, assessment and management of welfare outcomes, finishing accommodation, farrowing system, tail docking (and other procedures).

While most of the tiers would build on existing definitions under the voluntary industry-led Pork Provenance code, the biggest new differentiator would be between ‘standard’ and ‘enhanced’ indoor production.

To be in the ‘enhanced’ tier 3, indoor producers would need to have, for example:

- Bedded lying areas, with no slatted floors in finishing accommodation.

- Permanent access to environmental enrichment in sufficient quantities to ‘allow and encourage proper expression of rooting, pawing and chewing behaviours’.

- No conventional farrowing crates. Temporary crating (five days or less) would be allowed.

The draft standards account for pigs moving between different systems by specifying the minimum proportion of time a pig must spend outdoors to meet the highest two tiers.

Defra acknowledges that the standards would be based on inputs, and that ‘whilst welfare outcomes provide a more accurate representation of an animal’s individual welfare, it is not currently feasible to include outcome metrics in the standards’.

To counter this, it proposes that welfare outcomes assessments must be carried out on tier 3 farms and above, which could be conducted as part of a recognised assurance scheme.

Defra also acknowledged that a ‘robust system for monitoring and enforcement’ would be needed. It proposes that the Food Business Operator (FBO) – a supermarket for own-brand products or a manufacturer for branded products – should be responsible for accurate labelling and would need to have suitable traceability systems in place to ensure welfare claims can be ‘evidenced back through their supply chain’.

The consultation also asked whether there should be space on the label for an assurance scheme logo.

Industry reaction

The principle of more transparent labelling was broadly welcomed, but huge concerns remain within the supply chain about the MOP proposals.

James Bailey, executive director of Waitrose, said: “Better information boosts demand for higher standards, as we’ve seen with mandatory egg labelling. Extending this to more products benefits shoppers, farmers, and animals.”

Fidelity Weston, chair of the Consortium of Labelling for the Environment, Animal Welfare and Regenerative Farming (CLEAR) said the UK’s high farming standards need to be recognised in the marketplace.

NFU deputy president David Exwood said there was a clear need for better labelling to enable consumers to make a more informed choice.

“However, labelling on its own is not the answer to safeguarding our own high standards from imports produced under conditions that would be illegal in the UK,” he said, adding that the NFU’s election manifesto calls on the next government to enshrine a set of core environmental and animal welfare standards in law for all agri-food imports.

NPA chief executive Lizzie Wilson welcomed the plans for clearer COO labelling, including broadening this out to the out-of-home market.

But she warned that the MOP plans threaten to add significant cost and disruption within the supply chain without delivering any ‘meaningful’ new information to the consumer.

In January 2023, the heads of key supply chain organisations – NFU, NPA, British Meat Processors Association, the Food and Drink Federation, Dairy UK and the British Poultry Council – set out their concerns about MOP labelling in a letter to Farming Minister Mark Spencer, which led to a halt in proceedings.

But the concerns remain the same today. The need to define and separate supply lines, particularly the standard and enhanced indoor categories, which have never previously been demarked in this way, would be difficult, time-consuming and expensive for processing plants.

The process would be far more complicated than for eggs, where it has been a success, partly because of the various systems a pig can move through during its lifetime, as addressed in the consultation, and also because different parts of the pig carcase go into many different markets. “Individual pork cuts are often downgraded, so that would be difficult to label,” Lizzie said.

But the biggest concern is that the ranking system could mislead consumers about welfare standards on farm. “We need to avoid falling into the trap of claiming one system is automatically better than another, just because it’s environment,”” she added.

“Welfare is a reflection of many things, first and foremost the quality of the stock-keeping and the care and attention given to the animals. Method of production is not an indication of good or poor welfare – a good indoor unit can provide better welfare than a poor outdoor one.”

“There’s also a huge jump between the third and fourth tiers and yet the welfare outcome assessment will only be conducted on the highest three, which makes no sense when their objective is to improve on farm welfare.”

Lizzie pointed out that the current voluntary labelling system already provides consumers with clear information about system of production, giving them choice but without making potentially misleading welfare claims.

Adding an extra label to an already crowded packet, alongside current assurance schemes and nutrition labelling, with carbon/environmental labelling very much on the horizon, risks further confusing consumers, she added.

“It is also very unclear how this could be applied to imports,” she added. “We are certainly not opposed to increasing transparency and providing more information to consumers about how their pork is produced, but it has to be meaningful. We don’t feel these proposals would deliver that.”

Anna Longthorp, as a free-range producer, would, in Defra’s view, be a clear beneficiary of the proposed regime. But she is also opposed to it.

Anna Longthorp, as a free-range producer, would, in Defra’s view, be a clear beneficiary of the proposed regime. But she is also opposed to it.

“I don’t want compulsory MOP labelling because it’s not as simple as free-range good, indoor bad,” she said.

“There’s a lot of nuance in between – sometimes circumstances change, such as keeping pigs indoors for a while during a site move. You can’t just change your label for six weeks – it is very expensive.

“The current definitions already work – there is no need to change it.”

The consultation

- The consultation will run for eight weeks, closing on May 7.

- It is a UK-wide consultation from Defra and the devolved authorities.

- There are 73 questions in the 68-page document.

- You can view it HERE