The effects of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) have changed since it was first found in UK pigs 25 years ago, when it caused devastation through post-weaning multi-systemic wasting syndrome (PMWS), with post-weaning mortality rates of up to 30% in some herds.

Vaccination against PCV2 has been widely effective over the past 17 years and most PCV2 infection of pigs today is subclinical, which means the virus is present in the pig without it showing obvious clinical signs of disease.

In a proportion of such cases, it may cause reduced growth and increased susceptibility to other diseases.

See also: Tackling key viral diseases: a focus on swine influenza

A report by Alarcon P, Rushton J and Wieland B (2013) showed PMWS and subclinical PCV2 infection in England cost up to £8.10 per marketable pig.

Drawing together technical veterinary knowledge from across the pig industry, Zoetis hosts an annual two-day CPD event for younger pig vets, particularly those new to the industry.

The focus at the most recent event was on swine influenza, PCV2 and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS), the ‘big three’ viruses affecting pigs.

Discussing the changing nature of PCV2, Susanna Williamson, of the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), said: “Diagnoses of PCV2-associated disease (PCV2-D) have fallen dramatically since the early 2000s.

“We do still see pigs typical of PMWS, but surveillance data shows the clinical signs are more diverse now, with respiratory disease being another common presentation. Secondary bacterial infections are also common due to the immunosuppressive nature of PCV2-D.”

The age of pigs affected has also broadened and, in recent years, disease has been diagnosed in pigs aged three to 25 weeks, although most disease is still seen in post-weaned pigs aged six to 14 weeks.

A survey by APHA detected PCV2 virus in the serum of 16% of the healthy slaughter pigs sampled in 2019, confirming that PCV2 infection remains active in the national pig population, even where clinical disease is not evident, and remains a threat to unvaccinated pigs.

The virus is considered impossible to totally eliminate from herds, even with thorough cleaning and disinfection, partly because it’s very stable in the environment, is readily transmitted between pigs and can also be passed on in utero.

PCV2 virus has an affinity to fast-replicating cells within the pig, including immune cells, which replicate rapidly in response to infection. Therefore, as the level of disease challenge in a pig increases, it becomes even more susceptible to further challenge by PCV2.

Changing genotypes

“As well as the costs of clinical and subclinical disease, the evolution of the PCV2 virus poses another challenge,” said Zoetis national veterinary manager Dr Laura Hancox.

“PCV2 is a relatively rapidly changing virus – although less rapidly than viruses such as PRRS and swine influenza – as it has a stronger propensity to mutate over time than any other DNA viruses, and also to recombine, where different PCV2 viruses merge to form a new strain.”

PCV2a was the first PCV2 genotype to be identified and the one on which the first vaccines were therefore based. There are now nine genotypes of PCV2 classified from a to i, with the three most prevalent globally being PCV2a, PCV2b and PCV2d.

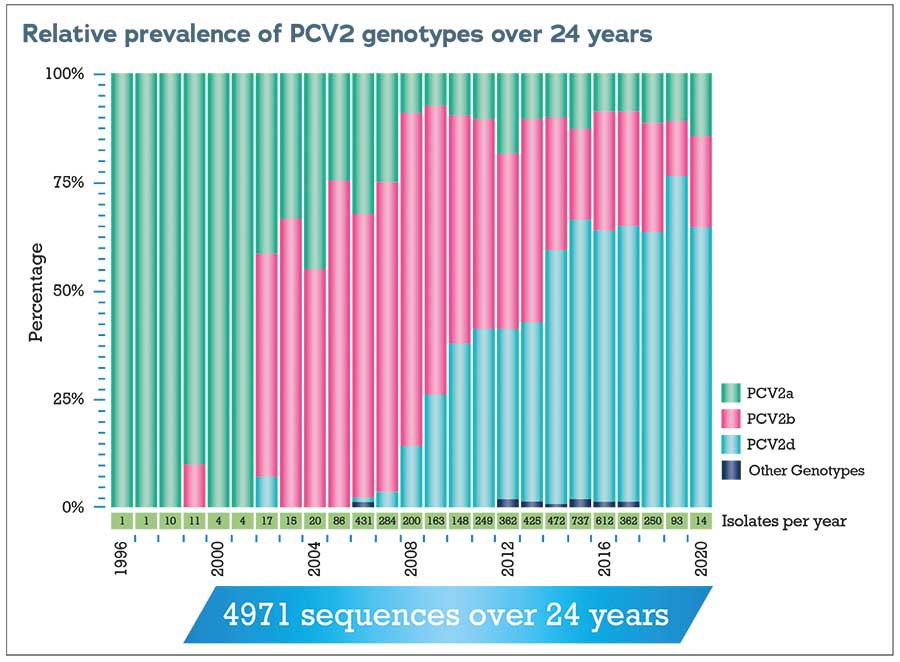

Since 2011, APHA has regularly genotyped the PCV2 involved in diagnoses of PCV2-d in diagnostic submissions from pigs in England and Wales to monitor changes in genotype and the appearance of new genotypes.

Since 2011, APHA has regularly genotyped the PCV2 involved in diagnoses of PCV2-d in diagnostic submissions from pigs in England and Wales to monitor changes in genotype and the appearance of new genotypes.

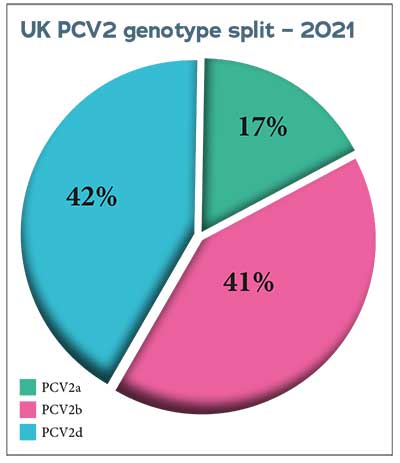

The predominant genotype in disease-associated cases has changed from PCV2b to PCV2d in the past decade.

Compared to swine influenza or PRRS, relatively few diagnoses of PCV2-d are made in Great Britain each year, but continued surveillance and readiness for any changes are vital.

“We need to keep monitoring PCV2 disease incidence and genotypes, and we appreciate all the information, samples and pigs provided to APHA by vets and their pig-keeping clients that help us to do that,” said Dr Williamson.

“Investigation of apparent vaccine failures is also vital, and vets should report any confirmed failure to the Veterinary Medicines Directorate.”

More information

- Pig veterinary professionals can contact Zoetis to request access to more technical information on PCV2 on Zoetis’ CPD portal, or to find out about this year’s Young Pig Vets Conference in November.

- Producers should seek advice from their vet if they have concerns or to review health management planning.

- To report suspected notifiable disease, call the Defra Rural Services Helpline on 03000 200 301 in England, in Wales contact 0300 303 8268 and in Scotland contact your local Field Services Office.

- Find guidance on ASF and reporting suspected disease online as well as images of the signs and pathology of ASF

Diagnosis of PCV2-associated disease

In order to investigate whether PCV2 is involved in disease outbreaks on pig farms, a thorough clinical history and inspection, and post-mortem examination of several affected pigs are all necessary.

Confirmation of a diagnosis of PCV2-D requires submission of pigs or samples to a diagnostic laboratory and detection of both typical microscopic changes in lymphoid tissues and of PCV2 by visualisation of viral inclusions, or immunohistochemistry.

Diagnosing any other diseases concurrent with PCV2-D is also important and helps the attending vet to advise on their treatment and control measures.

PCV2 can also be linked to porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome (PDNS), which can cause clinical signs and pathology resembling African and classical swine fever, such as acute illness, sudden death and red/purple skin lesions, with kidney haemorrhages and enlarged spleen and lymph nodes seen at post-mortems.

Dr Williamson emphasised that vets assessing disease incidents should be alert to the possibility of these notifiable diseases, which, if suspected, must be promptly reported to the Defra Rural Services Helpline. African swine fever (ASF) is, of course, of particular concern due to current outbreaks in Asia, Europe and the Caribbean.

Management and vaccination

Management to prevent or control PCV2 disease depends on the individual farm and is likely to include a combination of biosecurity, optimum environmental conditions, management of pig flow and vaccination.

Each farm’s situation is different, and Zoetis offers a service to identify the PCV2 genotype circulating on the farm to help decide which vaccine is most suitable.

Published research by Bandrick M, Balasch M, Heinz A et al (2022) has shown that the closer the match between the vaccine strain and the field strain, the more effective it is clinically.

It also shows that vaccines of different genotypes can provide some cross-protection – the dual-genotype vaccine CircoMax, containing both PCV2a and PCV2b, provides better protection than a single-genotype vaccine with PCV2a alone, according to Zoetis.

A study by Um H, Yang S, Oh T et al (2021) in a herd with subclinical PCV2d infection showed that vaccination with the dual-genotype vaccine (PCV2a and PCV2b) resulted in significantly greater immune response than a single PCV2a vaccine.

The PCV2d genotype has up to 97.7% genetic similarity to the PCV2b genotype, which is the likely reason why including the PCV2b genotype alongside PCV2a in the vaccine means it offers greater protection against the PCV2d genotype.

PCV2 monitoring – US experience

Routine, population-based monitoring is very useful to track PCV2 infection in a herd and make more informed decisions on its control, according to US vet Clayton Johnson, of Carthage Veterinary Service, in Illinois. He shared his experience of managing PCV2 in US pig herds.

“The fundamental point is that, because PCV2 is endemic, all pigs are very likely to become infected at some point,” he said.

PCV2 can infect pigs of any age and even pigs that are showing no signs of disease can shed the virus in their colostrum, milk and faeces.

In the US, they are most likely to see clinical signs at 10-26 weeks of age, and weight loss, respiratory disease and PDNS-type lesions are the most common signs seen.

“Vaccines play a big part in managing the disease, but we need to differentiate expectations. If pigs have appropriate maternal antibodies, they will have minimal disease, though that’s different to infection. Vaccination reduces viraemia, but does not eliminate infection,” Dr Johnson added.

Vets need to consider the timing of the sow vaccine to make sure that increased maternal antibodies do not adversely affect efficacy of piglet vaccines.

“In gilts, reproductive signs are not common, but can be severe,” he said. “While there are not often abortions, it can look a lot like parvovirus, with mummified piglets and stillbirths. It’s important to watch disease in gilts – generally, not just PCV2 – as issues can rumble on if they are lost in overall multiparous herd figures.”

Routine monitoring

Blood samples offer the opportunity to test for antibodies and, for routine monitoring of breeding herd stability, additional PCR testing can be carried out on samples of processing fluids.

These are fluids from removed tails and testicles (castration is commonplace in the US), also commonly used for PRRS monitoring, which can be regularly collected and stored.

Dr Johnson has found that PCV2 can sometimes be a ‘fallback’ answer for producers who might assume that, because it cannot be treated, it must be the reason for a problem – when there could actually be another issue that needs investigating.

Therefore, routine monitoring to provide baseline data on PCV2 disease stability can help avoid the opportunity for bias.

Defining the timing of infection also helps to remove any weight of bias and point to more effective intervention strategies. Genotype sequencing is now really important, with PCV2d having been the most common genotype on US farms for the past five to six years.

“On one farm we investigated, where problems were noticed in weaned piglets in early autumn, we had stored breeding herd samples available to test retrospectively, including cross-sectional viraemia

testing for the gilt development unit,” Dr Johnson said.

“September breeding herd samples brought back negative PCRs, then the PCRs were positive in samples taken in October, but there were still no clinical signs in the breeding herd – only a couple of positive results in colostrum. These were the early stages of the outbreak, and the farm mass-vaccinated the breeding herd in November.”

By January, mummies had increased across all parities from a target of 0.3 rolling average to between 0.5 and 1.1, and the diagnostic tests were positive.

Viraemia was still present in the gilt development unit 16 weeks after the outbreak began and it was another seven weeks after that, in spring, before the tests were negative – several months after the mass vaccination in November.

“This shows the value of routine, population-based monitoring for PCV2,” said Dr Johnson. “You can see trends and make interventions earlier.”

He warned farmers to beware of hyper-immunisation after mass vaccination of sows; high antibodies in colostrum may mean vaccination at weaning needs to be delayed.

He concluded by emphasising that interpretation of diagnostics needs context. “Quantitative PCR results such as cycle threshold values, along with clinical signs, help provide context beyond a positive PCR result,” he said.