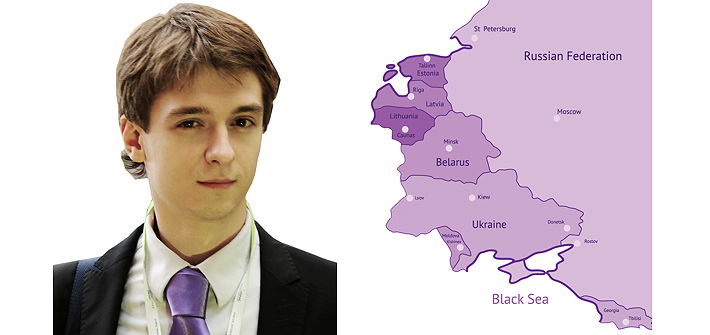

Most pig breeders in post Soviet Union states have had to face very negative market conditions with extremely low purchasing prices. Where efficiency of businesses has been low, this has left hundreds of pig farms of different scales facing bankruptcy. The one positive factor is that the spread of African swine fever (ASF) tends to slow down during the winter, but there are no doubts it will return soon.

Liveweight pork production in Russia last year totalled 3.96 million tonnes, which was 3.8% more than 2014, according to the country’s agriculture ministry. This figure met an estimated 78% of the domestic demand, so the there was a further reduction in pork consumption, which has now dropped nearly 9% in the past two years.

The director of animal husbandry and breeding at the ministry says that the country must reduce its dependency on top-level breeding stock imports, which he puts at 80 to 90% at present.

The agriculture ministry will, therefore, aim to modernise the existing breeding and genetic centres with an aim of reducing imports and the associated risk of importing disease. In addition, Russia plans to create at least five new centres for pig breeding, which will be located in regions that have been prioritised for development of the pig industry.

The situation in Ukraine’s pig industry is also quite unstable, with businesses hit by low prices. Prices in the country are currently at 65p/kg compared to a cost of production of 81p/kg.

According to the head of the Union of Pig Producers of Ukraine, Artur Loza, Ukraine’s farmers will produce about 740,000t of pork this year, the same as 2015, but in the past year the demand for pork has dropped by 13%, which is pushing prices down further.

There are some early signs of reduced insemination of sows, so the volume of production this year may drop a little, but the main hope for Ukraine’s farmers is increased exports. Last year, the country tripled exports to 27,000t (excluding deliveries to Crimea). The price from the foreign markets is usually more attractive than in Ukraine, even given the transport costs.

Already, large-scale supplies of pork from Ukraine to Moldova are alarming local farmers there. Last year imports reduced the price they were getting from a minimum 114p/kg to just 93p/kg. As a result, the country’s pig industry is facing its toughest crisis for more than 15 years and the average farm faces losses of £36,000 for every 500t of pork produced.

The Belarus pig industry faces a different challenge as it’s proving difficult to get the pig population back to the levels prior to the 2013 ASF epidemic in 2013. As of January 1, 2016, the number of pigs in the country totalled 2.75 million head. The number increased by 11.8% during 2015, but the country’s president has called on officials at the agriculture ministry to get numbers back up to 3.3 million head.

The deficit of pork production in Belarus has already resulted in the pork price increasing by 59.7%.

The problem facing Belarus pig farmers lies in the fact that the government has to choose between either increasing prices, supporting the profitability of producers’ businesses, but hurting citizens; or to constrain the price increases so citizens remain happy. Officials usually opt for the second route, but this would have resulted in the industry facing a lack of money to increase production capacity.

The situation in the Baltic States of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia continues to be challenging, with producers facing ASF and the Russian embargo. As a result, the average purchasing price for pigs in the region reduced from 98p/kg to 66p/kg last year.

Unfortunately, ASF appears to be having a paradoxical effect on the Latvian pig market. Even though the country is enjoying unprecedented low purchasing prices for pork, the population has cut its consumption. It’s not actually clear why that has happened, although it’s suspected some people think they can be affected by ASF. As a result, several pig farms in the country went bankrupt in 2015.

The situation is more complicated in the so-called ASF quarantine zones. The farmers operating in these zones are not allowed to deliver the pork they produce outside of their zone, and in some affected areas of Estonia have already seen 30% of producers going bankrupt. And most expect there will be more bankruptcies before the market finds a new balance.