Ben Williams, AHDB senior knowledge transfer manager, asks whether big data will become as important to agriculture as the tractor

Like the many hyped revolutions that have preceded it, is big data out of reach for most producers? In fact, would it be true to say that, for many reasons, it is not affordable, applicable or realistic for the majority of agriculture? Unless you are a pioneer, a large integrated business or a bit of a maverick, is it just too hard to truly work with big data?

At its annual conference recently, the Institute of Agricultural Engineers asked whether big data would revolutionise agricultural productivity in the same way the tractor has.

According to Ben Williams, AHDB senior knowledge transfer manager, the question is timely, with several claims being made around the benefits of using data, from improved efficiency and productivity to better prediction of consumer trends and promoting climate-friendly agriculture.

AHDB’s Precision Pig project looks at the data generated by individual pigs from sire to slaughter – some may argue this is big data (there is a lot of it, potentially).

Mr Williams said: “The titles we give projects can be misleading and bog down progress over semantics, but what we want to see is not big, small or any concept of data size, but actual data value.

“Data value is what will drive evolution in how we farm. We are looking for data that shows the outliers in production, previously hidden by averages – otherwise, there is simply no point tagging every pig.

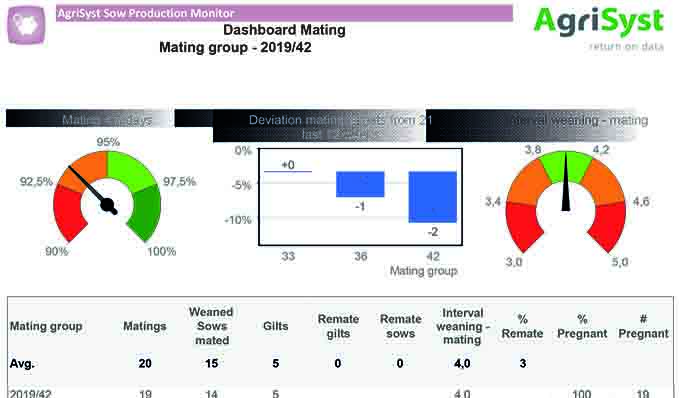

“Let’s assume you have 600 sows – you produce 30,000 pigs a year and send 600–650 pigs every week for slaughter. You may have software that tells you your average number of returns, parity of sows, conception rates, litter sizes, mortality, etc.

“You’ll get reports describing average slaughter weights, P2 and disease incidence. You may even be able to chart your average medicine use beyond antibiotics.

“This data has so far proven extremely useful – it makes pig production one of the most efficient production systems in agriculture, but the ‘average pig’ does not exist and, even if it did, it would be boring.

“The pigs that sit at the extremes are interesting – they either move much faster and can drive better performance through optimisation of their genetic potential or they are too slow and waste resource.”

The AHDB project combines precision technology, such as radio frequency identification tags (RFID or EID) and automated weigh systems, with software that takes data, regardless of where it is stored, and produces reports that deliberately pick out the outliers.

“Understanding which parts of the business are underperforming is important,” Mr Williams said. “Data on anything, from fertility right through to pigs meeting specification, can be captured and customised within the reports.

“The ultimate goal is to know whether the pig hanging on a gambrel in the abattoir with a defect that has cost money has had the same treatment as others in the batch. Were medicines effective? Or are there similar issues with pigs from the same pen? Did they come from the same sire or sow?”

The AHDB project has already mastered the linking of sire to sow to piglet using EID tags. In the new year, fuelled by industry energy and enthusiasm, the project will start gathering slaughter data on an individual animal basis and, importantly, linking it back, by proxy, to the sire lines. This will allow, through a single report, all the above questions to be answered.

Mr Williams said: “There is still a long way to go to answer the question posed by the Institute of Agricultural Engineers, but we do know where to start. Firstly, when selling a product that generates data, there shouldn’t be a cost to move that data from one system to another. In fact, without the ability to move and join data together, there isn’t enough value in it to warrant the cost.”

The technology and software still need some development before the full benefits can be realised. For example, low frequency (LF) tags are relatively expensive and have reading distance limits, but they are tried and tested and can be adapted.

Ultra-high frequency (UHF) tags have a much better read range, are much cheaper but have their own software limitations – they can struggle with multiple reading of tags, tag readings from reflective surfaces and the fact that UHF waves do not travel well in water and therefore the wet tissue of a pig’s ear can absorb the frequency.

“If truly valuable data is to be extracted from pig production, technologies like UHF need to be developed and better integrated,” Mr Williams added. “Technologies such as LF tags that have known limitations need to be pushed and adapted to work where people do not expect them to. Throughout the Precision Pig project, AHDB is seeing these technologies adapting.”

But the question remains, is putting an EID tag in every pig worth it? While there are other technologies for tracking individual pigs, EID is the simplest and currently most cost-effective. The Precision Pig project has costed the impact of using EID tags to track data from every pig, from sire to slaughter.

Over three years of depreciation, the tags, software for recording and hardware for reading equate to a cost of 1.39p/kg (typical 600-sow farrow-to-finish unit).

The same calculations show a 1% increase in efficiency/reduction in cost of production (based on 1.56p/kg – the UK average Q3 2018 costs) would lead to covering the full costs. A 5% increase in efficiency would pay back the return on investment five times over. These costings are based on a worst-case scenario and make use of the more expensive LF tags currently used in sows.

Mr Williams said: “Early indications show that using the technology improves marginal gains across production, labour, fertility, feed efficiency and getting more pigs in specification. One case study farm is streamlining data collection by using the mobile data collection device to allow staff to collect all the data while going about their work, rather than noting it in diaries, which have to be transcribed in the office later. This simple swap, using technology that has controls and checks already built in, has saved 0.1 p/ kg. Although it may not seem a lot, a small gain was made simply by swapping the diary for a handheld device.”

Automated weighing machines have been rolling out across the farms working under the project and these are allowing routine weighing to be completed significantly faster, saving money where it was already routine and making savings where it wasn’t.

Using the national data for Q3 2018, 26% of slaughtered pigs failed to meet specification, thus incurring a cost of approximately 3.9p/kg. There is potential to reduce the number of out-of-specification pigs by 5%, achieving a return of 0.78p/kg, which is well on the way to returning the cost of the investment.

So, is ‘Big Data’ the next tractor?

“If what we want is a revolution, to paraphrase the great philosopher Mick Jagger, we might not get what we want,” Mr Williams said. “But if we keep trying, we might just get what we need, which is a pig industry that recognises the pressures it faces from consumer demands around antibiotics and environmental efficiencies and can adapt to deliver a more individual notion of health, welfare and efficiency.

“The overwhelming factor influencing the adoption of this technology lies in the question: will it deliver valuable data? The answer would appear to be ‘yes’, and we have only just begun to scratch the surface.”