PRRS, which arrived in the UK more than 20 years ago, remains a debilitating disease due to the two-pronged attack it wields on both sow productivity and rearing herd performance. It’s also now endemic in most herds.

To their credit, pig producers have learned to live with PRRS, containing it via stringent biosecurity and the implementation of routine vaccination programmes. But with the pressure on to improve efficiency and maximise performance at every level, PRRS control is now stepping up a gear.

Stability is the watchword, and if your herd is PRRS positive, achieving and maintaining a stabilised status should be top priority. It has advantages, both clinically and economically, and could make a significant difference to business efficiency and profit potential. However, reaching this goal requires a different management perspective that’s more attuned to health screening than tactical response.

The multi-factorial nature of the PRRS virus allows it to thrive in situations where management is perhaps not as good as it could be, and where other disease complexes are active. Its ability to transfer from the breeding herd to growing pigs enables recirculation of the virus too, and it’s often difficult to identify specific areas in the production cycle where viral shedding occurs and infection is being passed on.

Although a confirmed diagnosis allows vets and producers to decide on appropriate control measures, maintaining a stable PRRS status can prove very challenging. This is an intricate, opportunistic virus and the tactics required to keep it in check need to be equally clever.

Vet Gemma Thwaites of the Garth Pig Practice in East Yorkshire sees PRRS as one of the biggest health challenges currently facing UK herds.

“Now PCV2 is under control in most herds, we can really see the effects that PRRS is having on pig health and it’s surprisingly considerable,” she says.

Although most herds do use PRRS vaccination programmes to protect their pigs, Gemma says the continuous monitoring of an individual herd’s PRRS status provides a valuable insight into how this disease is affecting productivity and ultimately business efficiency.

“For a herd to optimise its genetic potential and achieve top performance it must have a stable health status, but if PRRS is circulating, achieving this can be extremely difficult,” she explains. “Farms that are challenged should be aiming to stabilise their situation and minimise breakdowns.

“Being able to break the infection cycle and prevent recirculation between the breeding and rearing herd is the key, and it will benefit herd health and productivity.”

Screening sense

But establishing this level of control requires much more than just a vaccination strategy and/or opting for a closed-herd policy. Producers must also implement stringent management controls, tough hygiene and biosecurity protocols and commit to a comprehensive screening process, involving regular diagnostic tests and clinical reviews.

Gemma says a number of Garth’s clients are beginning to recognise the value of a more structured, proactive health plan. Such a strategy includes frequent surveillance and disease monitoring activities, combined with ongoing veterinary guidance. A number of herds are now using regular ELISA and PCR tests within their PRRS control strategies as these investigative procedures provide valuable clinical information and in some herds have helped to identify problems in advance of any clinical presentation.

“To manage PRRS effectively you need a good understanding of how the virus is functioning throughout the herd,” she adds. “You need to know what’s happening in both the breeding and feeding herds and whether the situation is stable or volatile, which is why diagnostics are important. The more information your vet has about your herd’s health status and how it is evolving, then the better equipped he or she is to develop effective, workable treatment and control strategies.”

Diagnostics tests can be used to:

- provide on-going information on how pigs are responding to management protocols and any treatment and control programmes that are implemented;

- assess the clinical and sub-clinical levels of disease that exist in a herd and/or identify specific periods of activity within the production cycle;

- help indicate where potential breakdowns are occurring, are likely to occur and detect any new or emerging challenges.

Many vets believe there’s a strong case for commercial herds to include more screening within their PRRS management plans. Diagnostic tests are often available through veterinary practices – for example MSD Animal Health offers a selection of diagnostic tools – including a PRRS ELISA (Vetcheck) and PCR tests (Respicheck) – that vets can use free of charge.

Gemma says that one breeding and finishing unit that recently added routine diagnostic testing (ELISA and PCR) to its PRRS control policy is now reporting a 30% reduction in the number of viraemic pigs in its rearing herd. The business altered its disease management strategy in response to initial test results and now has a more stabilised health status in both its breeding and rearing pigs. The outcome has been a reduction in mortality rates and significantly better performance from weaning to slaughter.

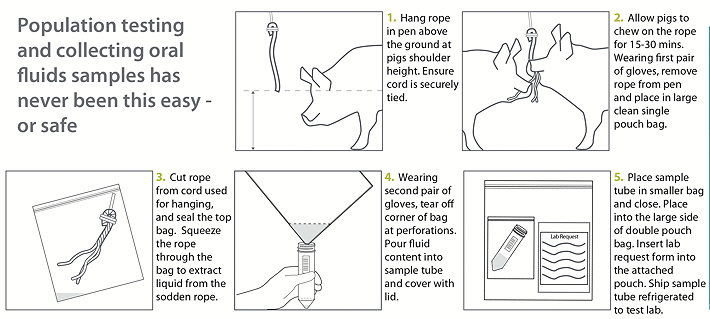

A number of Garth’s clients are now using saliva samples to monitor the PRRS status of their growing pigs. Rope ‘chews’ are hung in pens a few days before the quarterly vet visit and samples are submitted for ELISA tests. The vet can then discuss the results with the client during their visit, and follow up blood tests can be taken if required. These diagnostic tests are subsidised by MSD’s Vetcheck and Respicheck service, and the feedback from farmers has been favourable.

“The ropes are a useful, non-invasive means of collecting clinical data, and when combined with other tests can help us build a clearer picture of health status and see if the PRRS situation is changing,” Gemma says. “It’s another tool in the box, it works well and is enabling pig farmers to keep pace of developments and hopefully head off potential problems.”

Positive, possible and profitable

For most commercial herds achieving a positive, stabilised PRRS status is a realistic target.

Farms that are stable have no evidence of clinical disease and are usually in a much better position to control viraemia in their growing pigs and so cut down the recirculation of PRRS virus in their herds. However, reaching this goal does require investment, considerable veterinary input and a commitment to persevere because the field challenge is relentless, says MSD’s technical manager, vet Ricardo Neto.

“Eradicating PRRS is virtually impossible for many herds or not even desirable, but improving herd health need not be limited by the threat or existence of this virus in a herd,” he adds. “PRRS can be managed effectively on farm and diagnostics have a key role to play here. Surveillance, alongside a strategic vaccination programme using a proven vaccine such as Porcilis PRRS, can produce some very favourable results, both clinically and financially.”

Diagnostic tests such as those offered by MSD allow vets to continually monitor the health status of breeding sows and their progeny from weaning, and throughout the growing and finishing period. They can also be used to investigate and assess other pathogens that might be part of the respiratory disease complex too, such as PCV2 and swine flu.

But producers mustn’t discount the vital role good husbandry skills and practical management expertise also has in minimising PRRS infection. Control strategies might be becoming more technical, but Ricardo says structured farm audits are equally valuable and can help vets and producers identify areas where management improvement and greater attention to detail could lead to better control and improved productivity.

MSD has recently relaunched www.respig.com, a web-based audit that can assess factors that influence PRRS activity, such as gilt replacement and rearing policies, pig flow, stocking densities, ventilation management, all-in/all-out batch production, nutritional management of the feeding herd and cleaning regimes.

And when vets input a herd’s performance data, Respig can also evaluate how an existing PRRS control programme is performing in line with current health status and physical performance. An independent economic simulator can also calculate the value of any proposed management changes and/or the introduction of a vaccination strategy, and determine if such measures offer a viable return on investment.

“The more we learn about PRRS and the intricate ways it affects pig production, then the better we’ll become at protecting our herds from it,” Ricardo says. “By providing vets and producers with robust diagnostic tools, structured evaluation services and proven and effective vaccines, MSD can support what really is one of the UK’s pig industry’s biggest challenges: to stabilise PRRS where it matters, out there on our farms.”