With high temperatures and ever-increasing issue for UK pig producers, Primary Diets’ Dr Phil Boyd looks at what producers can do to mitigate against the challenge.

Temperature is recognised as the single most important environmental factor affecting pork production efficiency globally.

“The phrase ‘climate change’ has evolved in recent years into ‘climate emergency’ and while we must remain hopeful that political leaders will agree decisive action to limit further damage to our planet, it is highly likely that, even in temperate climates such as the UK, we are going to face increasing levels of challenge in terms of the impact high temperatures have on our farmed livestock,” said Primary Diets’ senior nutritionist Dr Phil Boyd.

“Whilst the UK may be relatively blessed in terms of the magnitude of the heat challenge relative to those we compete against, as we enter the heart if summer, it is well worth revisiting some basics in relation to the effects of temperature on pig performance and considering what UK producers can and should do to mitigate it.”

Back to basics

- All pigs have an optimum temperature range that they would like to live in, which lowers as the animal gets older/heavier. As such, the effects of heat stress are of significantly more concern to older finishing pigs and adult stock than they are for younger animals (< 50 kg) – see Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Stages | Days | Comfortable zone Ta | Lower critical temperature ℃ | Upper critical temperature ℃ |

| Suckling piglets | Born | 35-32 | 30 | 37 |

| 1~3 | 32-30 | 28 | 37 | |

| 4~7 | 30-28 | 23 | 37 | |

| 7~28 | 28-23 | 23 | 37 | |

| Weaning / nursery | 29-40 | 28-25 | 23 | 30 |

| 40-80 | 25-20 | 18 | 30 | |

| Grower / finisher | 81-180 | 22-18 | 15 | 27 |

| Boar | 18-15 | 10 | 25 | |

| Gestation sow | 20-15 | 10 | 27 | |

| Lactation sow | 20-18 | 10 | 27 |

- Finishing pigs and adult stock begin to feel the negative effects of heat at around 20˚C – many UK finishing sheds will be above this temperature for large parts of the summer period.

- Pigs, generally, are highly susceptible to heat stress because, unlike us, they lack functional sweat glands and are highly reliant on convective and conductive heat loss. Our modern day, very lean pigs are particularly susceptible as high body protein turnover rates add significantly to their metabolic heat production.

- Generally, pigs try to minimise the effect of heat stress by two main methods – heat dissemination and a reduction in heat production. Increased heat dissemination is achieved by the pigs ‘sprawling out’ as much as possible, ie increasing the body’s contact with the cooler floor, and by panting, whereas a reduction in heat production is achieved mainly through an undesirable reduction in feed consumption.

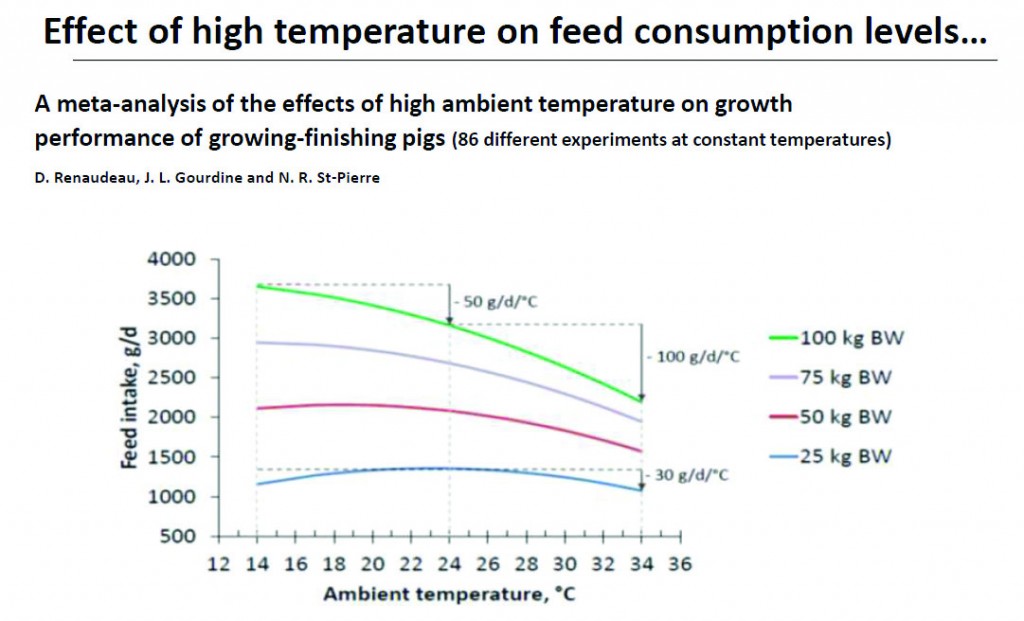

Graph 1

- As well as a reduced voluntary feed intake, under conditions of severe heat stress, animals can become more susceptible to immune challenge as a result of damage to the intestinal wall structure, which reduces feed efficiency and can cause further feed intake reductions.

It is therefore imperative for pig farmers to maximise heat dissemination and minimise the animal’s need to reduce its own heat production by dropping feed intake or, worse still, allowing the excess heat to cause damage to the pig’s gastro-intestinal tract, Dr Boyd said..

Maximising heat dissipation

Maximising heat dissipation is entirely under the farm’s control and how effectively this is achieved will be a significant variable from farm to farm.

- Stocking densities can theoretically be managed to both lower heat output and allow the pigs more room to fully ‘lay-out’, achieved via off-site finishing or selling a proportion of the pigs at an earlier age. It is appreciated that the practicalities of achieving this on an ‘as required basis’ are obviously not easy.

- Flooring type also impacts on the amount of heat dissipation achievable (slats best – then solid – then straw), but, like stocking density, this is not something that is particularly easily modified once the farm is established, apart from using less straw, therefore living with dirtier pigs.

- Ventilation is a vitally important tool to help manage heat dissipation in finishing pigs and, as UK temperatures increase, ventilation systems will be being modified to allow for faster air speeds, with the moving air directed at the pigs in the hotter summer months. All ventilation systems should already be subject to routine maintenance and cleaning schedules to ensure the system in place is running optimally, but as our summers continue to warm, this routine task becomes even more important. Many UK pig buildings were built some years ago and, in some cases, expert advice will be beneficial to see whether the original ventilation system is still ‘fit for purpose’. It is important to recognise that:

- Dirty louvres/fan blades can decrease efficiency by as much as 30%

- Excessive static pressure can negatively impact a fan’s exhaustive air capacity

- Slipping fan belts (where used) decrease RPM and reduce exhaustive output

- Cooling systems are not yet commonly seen on UK farms, but could be a relatively cheap ‘retro-fit’ for some that are tried, tested and proven in many parts of world. Sprinkler systems would be the most commonly used cooling system for finishing pigs, relying on the principle of evaporative cooling from the pig’s skin, but water pad systems and fogging systems are also used, even in Europe, to reduce air temperature.

- Water supply becomes ever more critical with higher environmental temperatures, with heat stress leading to a significantly increased water demand. Drinker provision – number, design and location – should be reviewed and water flow rate (by drinker/by building) regularly monitored. Drinker location relative to the feeders also merits attention, with clear performance advantages reported repeatedly for wet-dry feeders compared to conventional ad-lib (dry feed) troughs. Cooled water is not widely used yet, but from available research data, this lack of adoption, certainly in some parts of the world, should be more strenuously challenged.

Feed intake

“Undoubtedly, despite all efforts to maximise heat dissipation, at certain times of the year feed intakes of finishing pigs and lactating sows will suffer as a result of high temperatures,” Dr Boyd added.

“In this situation, the farm should work closely with their feed supplier or appointed nutrition advisor to appropriately adjust the rations used to both try to reduce heat output, to provide protection against the adverse effects of heat stress and to reflect the lower feed intakes seen.

“In countries where summer temperatures are predictably hot, nutritionists automatically adjust rations ahead of the heat, whereas in the UK, with currently less predictable hot weather and still significantly lower levels of problem due to excessive heat, it is still more common for people to react to change, rather than act ahead of the change.

‘Monitoring daily feed intakes and water consumption levels is becoming ever easier and cheaper, and whilst always important – a nutritionist simply cannot formulate properly without feed intake information – as our climate continues to warm, such an approach should be seen as an essential aid to try to minimise, as much as possible, the potential negative effects that hot weather can bring.”