There has been growing concern within the industry about the steady rise in swine dysentery (SD), the damaging enteric disease that has been affecting many pig premises across the country.

SD has a significant effect on pigs and producers, with productivity badly affected and partial or total depopulations often the only remedy to address a disease that is notoriously difficult to get rid of.

There has been an increase in reported cases through AHDB’s significant diseases charter and reports compiled by the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA).

Dr Claire Scott, veterinary lead of APHA’s Pig Expert Group, said: “An upward trend in the number of diagnoses of the disease through the Great Britain scanning surveillance network has been noted since the end of 2021.

“Cases have continued this year. In the first three months of 2024, 12 diagnoses were made on nine pig premises in four counties in England – Norfolk, East Riding and North Lincolnshire, Derbyshire and Northumberland – and one in Scotland.”

This has continued into the summer, with five cases notified via the charter in the first three weeks of August – four in Norfolk and one in Yorkshire.

What causes swine dysentery?

SD is caused by the bacteria Brachyspira hyodysenteriae.

There are seven other brachyspira species that can colonise swine, some of which are considered exotic to the UK, but are generally considered less pathogenic than Brachyspira hyodysenteriae.

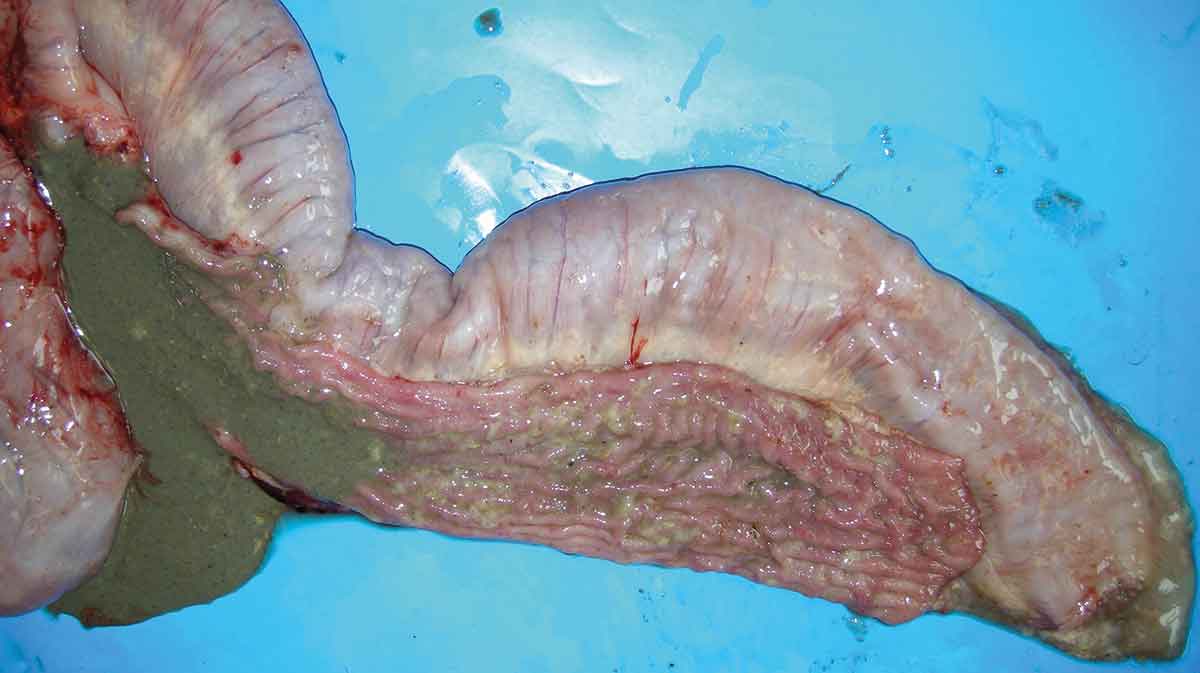

SD is characterised by diarrhoea, which can contain blood and mucous, although not in all cases, alongside weight loss and up to 30% mortality rates.

However, recent cases have generally been relatively mild, making diagnosis a bit harder.

Dr Mandy Nevel, AHDB head of animal health and welfare, said: “Clinical signs with any infectious disease will change over time.

“Initially, they are often more severe, but become less so, and we have seen this with SD. It’s not the same as it was 20 years ago and, therefore, we don’t always get the classic blood in the faeces.”

This point was reiterated by NPA senior policy adviser Katie Jarvis, who added: “Producers must ensure staff know the signs of dysentery. We understand that the strains circulating currently do not always show typical symptoms, so if producers do see unexplained diarrhoea or wasting, they should contact their vet.”

Dr Scott added: “Veterinarians have noticed that some confirmed cases of swine dysentery have been in pigs showing mild to moderate diarrhoea, rather than diarrhoea with mucous and blood, as has typically been associated with the disease.”

How is it spread?

The disease is spread by infected pigs, their faeces and any fomites that can transmit the infected faeces, such as vehicles, equipment, people and manure.

“Wild birds are also considered a possible means of spread by transferring infected pig faeces or, with some less common brachyspira species that have been found in wild waterfowl in other countries, by being infected themselves,” Dr Scott added.

Dr Nevel pointed out that it is not just large commercial units at risk and some cases could be spread at agricultural shows by pigs from small-scale units.

“Animals are tested before transport and even if swine dysentery is not found, with the stress of getting to the show, pigs can then start excreting it. Any stress can bring on clinical signs,” she said.

This is supported by research by Burroughs (2016), who found that when pigs are infected with B hyodysenteriae alongside other micro-organisms, disease expression is increased, demonstrating that stress and environment have a big role to play in the severity of SD.

Challenges

Most pigs can recover from SD over several weeks, but growth rates remain depressed, and prolonged periods of diarrhoea lead to dehydration and weak or emaciated animals.

Dr Scott reiterated the challenges: “Diseased pigs take longer to reach slaughter weight and compromise farm productivity and economic viability. SD is a particular threat to farms selling pigs for breeding; if these become infected, the farm’s international and UK trade can be devastated.”

Ms Jarvis added: “In cases where the farm is unable to get on top of the disease, it is usually managed by full or partial depopulation, so there is a financial disruption as well as the loss of the pigs.”

Depopulation, when SD is confirmed, is not a legislative requirement. However, it is often needed to eradicate the disease.

Therefore, preventing infection in the first place through strong biosecurity practices is critical. While clinical signs of swine dysentery can often be reduced using antibiotics, Dr Scott advised producers to consider using alternative interventions to antibiotics for long-term disease control.

Preventing resistance

All-in, all-out management systems, cleaning and disinfection procedures and partial or total depopulation leading to eradication can all play a part in preventing the development of wider antimicrobial resistance from treating SD, Dr Scott said.

Once a diagnosis of SD is confirmed, isolates undergo antimicrobial sensitivity minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing to indicate the likelihood of resistance to antimicrobials licensed for the treatment of SD, she explained.

“There is one particular sequence type (ST251) that has shown clinical resistance to some antimicrobials licensed to treat swine dysentery. ST251 isolates accounted for about 30% of the sequence types identified from 2021 to the first quarter

of 2024.

“By comparing isolates from before 2017 with those from 2017-2023, we can see that the isolates from 2017-2023 tend to be more sensitive to antimicrobials.

“Thus, apart from ST251-associated cases, clinical antimicrobial resistance does not appear to be a main factor behind the increase in swine dysentery diagnoses,” she said.

“However, there is always a risk that resistance of B hyodysenteriae to antimicrobials used in the control of swine dysentery could leave veterinarians unable to treat the disease.”

Preventing infection

It all highlights how important it is for all pig farms to take action to mitigate the risks of infection. With this in mind, advice from APHA, NPA, and AHDB includes:

- Look hard at biosecurity practices and make improvements where necessary.

- Undertake regular on-farm audits with the site veterinarian to identify and address biosecurity weak points.

- Pig lorries coming onto sites must be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected, both inside and out, between each use, in line with the Muck Free Truck campaign messages.

- If you have any suspicion that your unit has SD, speak to your vet

- Report diagnosis to the AHDB significant diseases charter. If diagnosis can be completed quickly, disease control measures can be put in place to limit the further spread of SD.

If attending veterinarians suspect SD, they can send faeces or pigs for testing at APHA, which can help veterinarians to determine the correct course of treatment.

“If we want to eradicate or control SD in the UK, early and correct diagnosis and prompt treatment is the key,” said Dr Nevel.

Significant diseases charter

Pig farmers and vets have, again, been urged to ensure they report cases of swine dysentery to the significant diseases charter.

The charter aims to help control disease quickly and effectively by sharing information on swine dysentery and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) outbreaks, including broad location, although it does not identify individual producers.

Notifying cases via the charter is a requirement under the Red Tractor assurance scheme.

There has been concern that the number of cases that have been notified via the charter this year is not tallying with the higher number of outbreaks being confirmed by APHA.

NPA senior policy adviser Katie Jarvis said: “The recent spike in swine dysentery cases is a real cause for concern. It is, therefore, vitally important that cases are reported to the charter, which alerts other producers and those from the allied industries to nearby cases. A failure to do this only heightens the risk of wider spread.”

Helpful links and resources

- Specific guidance on swine dysentery from AHDB

- Pig producers are encouraged to read more about and sign up to the significant diseases charter

- AHDB’s webpage on the #MuckFreeTruck campaign contains lots of useful information, including on how visitors should employ appropriate biosecurity before, during and after visits

- Further guidance on sampling for swine dysentery through APHA is available online.