Geoff Hooper of Hysolv Animal Health UK says it’s vital that producers take advantage of the free services available to evaluate the level of swine flu circulating in the UK’s pig population. The disease is widespread in pig herds and can cause significant economic losses to pig farmers. Many producers, however, may not be aware that the opportunity to monitor swine flu in their herds is readily available through their vets.

The cost of laboratory work is covered by government bodies and by vaccine manufacturers, which collaborate to help prevent the spread of disease. Use of an appropriate vaccine is the obvious course of prevention, along with biosecurity measures as viruses per se are not combated by the use of antibiotics.

Monitoring involves laboratory analysis, and this is free of charge as part of the UK and European monitoring system. The purpose of the monitoring is to help develop methods of controlling the effects of influenza epidemics in both humans and animals to reduce the risk of future epidemics or even pandemics. Monitoring will help identify any shift in the make-up of the swine flu virus.

Viruses evolve and change due to mutation and genetic drift. They can combine with other viruses infecting the animal concurrently. For example, they can interact and combine with other closely related virus strains, possibly resulting in the emergence of new strains. Some new strains could be more serious in their disease-causing effects and virulence, which can be a cause for concern. It’s therefore important to monitor strains currently circulating in the pig population. Species such as pigs and poultry have, in the past, been implicated and shown to be a “mixing pot” for viruses.

Widespread prevalence

Swine influenza A virus is widespread in herds, although due to its relatively low mortality rate in pigs it’s not designated as a notifiable disease. Swine flu is part of the porcine respiratory disease complex (PRDC) that also includes other viral and bacterial pathogens such as the Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) virus, porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV), Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Streptococcus suis and Pasteurella multocida. These are also responsible for complications in the course of an influenza infection.

After surviving an infection, animals may experience an extended period of reduced vitality; lowered daily weight gains, impaired reproductive performance and reduced disease resistance with consequential economic losses for the pig producer.

In its acute form, the disease spreads rapidly through the herd. The classical clinical picture of swine influenza develops after a one- to two-day incubation period and includes high fever, lethargy and lack of appetite. Other symptoms include nasal discharge, conjunctivitis and laboured breathing, the latter especially when the pigs are startled.

The characteristic barking cough develops on day three to four post-infection. All age groups may be equally affected, although the course of the disease can be milder in weaners.

In pregnant sows it can lead to abortion and stillbirth and the birth of sickly piglets.

If influenza infection is not complicated by any other infectious pathogens, the animals recover in about six to seven days.

Morbidity is high and can reach 100% in a susceptible herd. However, in classical cases, the infection is short-lived. While mortality is generally low, losses in production can be significant.

Chronic disease

A much milder form of the disease is now being observed with increasing frequency. In this form, the virus circulates within the herd and may cause slowly spreading infections. Here, the clinical picture is characterised by non-specific respiratory problems, a reduced vitality and fertility disorders.

Typically, especially in newly-weaned piglets or older weaners, a persistent, sporadic mild cough is observed in a few animals in a pen without raising suspicions of influenza infection. If these animals are then subjected to stress, for example rehousing, the clinical picture may be aggravated. In this case, establishing a diagnosis is much more difficult and only pathogen or antibody detection by use of blood samples or nasal swabbing can provide a reliable diagnosis.

Besides better biosecurity and taking steps to improve herd management – including checking climatic conditions and stocking density in the pig houses – vaccination is a safe and effective preventive measure. Current vaccines will provide protection against strains contained in the vaccine, for example H1N1, H1N2 and H3N2, account for a majority of currently identified strains.

Detection and monitoring

A diagnosis of influenza infection based solely on the clinical picture is always purely tentative due to the lack of characteristic (pathognomonic) clinical signs and the existence of other possible causes of respiratory disease in pigs such as infections with PRRS, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and so on. A meaningful diagnosis can only be established in combination with laboratory diagnostic methods.

Virus detection methods are either direct or indirect. Direct methods include the detection of viral antigen, nucleic acid or the entire virus on the basis of nasal swabs, saliva samples, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or pulmonary tissue samples. An indirect method is the detection of antibodies to influenza A viruses in blood serum samples.

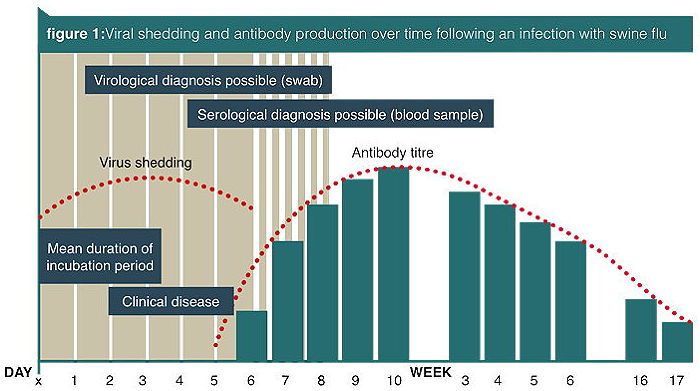

Figure 1 shows viral shedding and antibody production over time. Here, the timing of virus shedding and antibody formation is clear.

Viral shedding is at its highest in the first three days post-infection, while antibody titres reach a peak at nine to 10 days and begin to decline from week three onwards. This means there are two windows for monitoring infection, and the most useful one for identifying the actual strain is by nasal swabbing.

If a pig farmer suspects his herd has an infection, samples can be taken by his vet ideally within the first few days (one to five) so that the virus can be fully typed using newer real-time PCR analysis to screen and identify the actual strains, which have a genetic fingerprint. Blood samples can be useful to identify the disease is present, but they will not provide the important information as to the origin of the virus.

Nasal swabs taken during the viral-shedding period offer the opportunity to closely identify the viral strain or strains; several may be present at the same time on the farm.

More information about swine influenza can be found at: www.swine-influenza.com