At its worst, post-weaning diarrhoea (PWD) can hit up to half the young pigs on a unit, with mortality in moderate to severe outbreaks increasing by 2-7%, although losses can be far greater.

Average daily gain can fall by as much as 35% in the first three weeks, as feed costs shoot up by 9% and pigs can take an extra 10 days to reach market weight.

For example, the losses from 5% mortality on a 500-sow unit would be more than £26,000, based on the 2015 UK average sow output of 26.2 piglets and April’s 7kg £40.81 weaner price.

The cumulative cost to producers is shown to be typically £3.63 (€4.35) per weaned piglet – and that’s every piglet weaned, not just those affected by PWD.

Yet, while the figures reflect the impact of moderate to severe outbreaks, another PWD-related problem is draining resources.

Veterinary surgeon Ciara O’Neill, of Elanco Animal Health, said: “There is a mindset that a certain, lower level of PWD is normal and becomes acceptable to some producers.

“This situation can go on for years, with continual or frequent outbreaks chipping away at performance and profitability. The costs over time can be enormous, but with fairly simple action this drain on resources can be plugged.”

PWD occurs typically in the first three weeks after weaning. The presence of diarrhoea is the most obvious clue that units have a problem. Decreased weight gain is not so obvious initially, but PWD is one of the most significant causes of mortality in weaned pigs worldwide.

“This underlines the need to resolve the problem whether an outbreak is moderate, severe or low level,” she added.

One, and perhaps the most recent, solution to ongoing, low-level problems is a vaccine that gives protection against F4- and F18-positive strains of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), which cause almost 60% of PWD cases in Europe.

The single-dose vaccine, Coliprotec F4/F18, provides piglets with active immunisation from 18 days of age.

It is administered via drinking water – in water tanks, by use of medicator pumps or drinking bowls – or by drenching piglets individually.

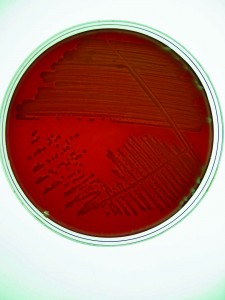

ETEC is the main cause of PWD in pigs and includes strains that produce one or several enterotoxins that induce diarrhoea in weaned pigs.

A major transmission route for ETEC is when pigs have eaten dung. Initially, young pigs acquire E. coli from their mothers, or from contaminated farrowing crates or pens. The contagious nature of PWD promotes pig-to-pig transmission in nursery accommodation. Replacement stock can also bring new strains of E. coli with them.

In spite of PWD’s impact on production, recent data documenting the prevalence of the various types of E. coli in Europe has been limited.

“There is a mindset that a lower level of PWD becomes acceptable”

One study last year attempted to plug the holes in our knowledge, covering almost 900 samples from 280 pig farms in Belgium and the Netherlands, France, Germany and Italy (Table 1).

The study showed that, overall, an average of 59.6% of units in Europe were affected with ETEC, while the bacteria was present on 81% of farms in Italy and 47.1% in Germany. A further study in Spain found 63.3% of diagnosed units were affected by ETEC and another study found 82.4% of farms affected in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Other work by Elanco Animal Health in the UK and Republic of Ireland showed that ETEC is frequently found on farms suffering from PWD.