What do the best herds in the UK and Denmark do in the farrowing house to achieve high levels of performance? This was the starting point for a survey to identify key management practices for further investigation during current AHDB Pork field trials on the topic, according to John Richardson of Production Performance Services.

Top-performing indoor breeding herds in the UK are producing about 30 pigs weaned per sow per year, which is equivalent to average herds in Denmark; the UK’s average indoor herds achieve 25.7 pigs per sow per year.

To find out more about what makes the difference, a 130-point questionnaire was completed by 12 UK and three Danish herds (11,310 sows) to profile herd structure and management systems. The results proved to be quite diverse, as were the farms in their management and housing. For example, one farm had a 35-year-old farrowing house, while another routinely kept sows to eight parities and some did not use covered creeps.

But, in short, the stockperson’s attention to detail was the major distinguishing factor, particularly with regard to split suckling, fostering, use of nurse sows, attention to teat number and size, “loading up” gilts and managing any fading pigs.

Personally, I feel that many UK pig producers have a different mindset to those in certain other EU countries when it comes to increased litter size, fearful of too many small pigs and higher mortality rates, or poorer post-weaning growth rates. Neither of these factors are particularly evident in high-performance herds in the UK or the more extreme Danish herds because they upgrade their management.

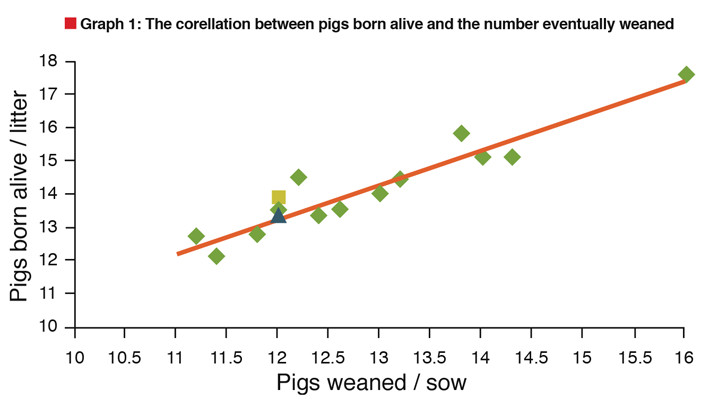

First and foremost, graph 1 confirms that more piglets born alive per litter is correlated to more piglets being reared. The four highest performing herds (top right on the graph) all used Danbred genetics. The best performer averaged 17.6 pigs born alive and 15.9 piglets weaned per sow farrowed.

This producer felt it was economically viable to aim for even higher numbers of pigs weaned by improving his replacement stock (he was weaning 37 pigs/sow/year on average, although this had reached 39.2 in recent months). UK herds averaged 12.1 pigs weaned weighing 7.6kg (a litter weight weaned of 92kg) whereas Danish herds averaged 14.9 pigs weaned weighing 6.3kg (a total litter weight weaned of 94kg).

This producer felt it was economically viable to aim for even higher numbers of pigs weaned by improving his replacement stock (he was weaning 37 pigs/sow/year on average, although this had reached 39.2 in recent months). UK herds averaged 12.1 pigs weaned weighing 7.6kg (a litter weight weaned of 92kg) whereas Danish herds averaged 14.9 pigs weaned weighing 6.3kg (a total litter weight weaned of 94kg).

So what were these herds doing management wise? The following highlights some of their key characteristics, although we must be careful of drawing too many conclusions because of the limited sample size.

Production cycles

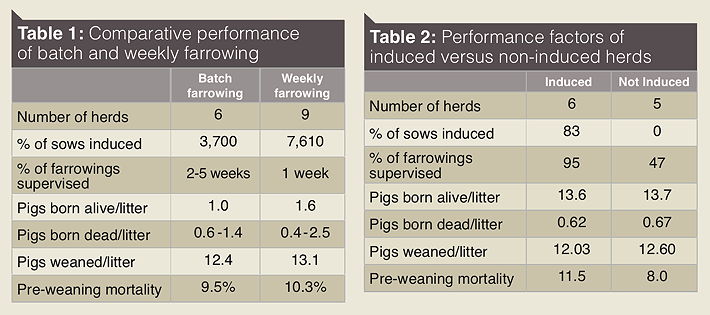

Batch production (two, three and five weekly) is primarily done to improve health of pigs post-weaning and to improve labour efficiency rather than pigs weaned per litter per se. This is highlighted by the number of hours of supervision per sow farrowing (1 hour/sow for batch farrowing – including night time cover in some herds – versus 1.6 hours/sow for weekly farrowing).

Weekly farrowed herds had greater supervision and also higher numbers born and reared per litter. These herds, however, were also less likely to be inducing sows and more likely to be routinely using nurse sows, which might be interacting with variables affecting the number weaned (see table 1).

Induced farrowing

Danish herds tended not to induce sows to farrow, so only UK herds are included in table 2. Numbers born alive and dead were similar for both groups, but non-induced herds weaned 0.57 more pigs per litter. If this is a true effect, could this be due to higher birth weights for non-induced sows because piglets were more likely to be closer to term?

The use of oxytocin or Reprocine during farrowing varied widely in the UK (neither product is licensed for use during farrowing in Denmark) and strategic use of oxytocin in eight UK herds was used at low levels – and typically in less than 15% of sows. The frequency of giving internal examinations averaged 13% of sows with a range of 3% to 30%; Danish herds tended to do more “internals” – probably as a consequence of not being able to use oxytocin during farrowing.

Once born, only one herd routinely physically dried small pigs to prevent chilling. Three herds provided significant amounts of shredded paper, wood shavings or chopped straw, three herds used Staldren-type dust products and Danish herds tended to use potato starch powder to assist drying off. All herds used a combination of lamps and heat mats.

Once born, only one herd routinely physically dried small pigs to prevent chilling. Three herds provided significant amounts of shredded paper, wood shavings or chopped straw, three herds used Staldren-type dust products and Danish herds tended to use potato starch powder to assist drying off. All herds used a combination of lamps and heat mats.

Split suckling, to ensure that all piglets received adequate intakes of colostrum, was routinely done by 11 of the 15 herds and was usually done twice per litter. The main trigger for this was litter size, and most herds aimed to have 14 to 15 functional teats per sow. Six of the 15 herds then also provided supplementary milk, for periods ranging from less than one week to three weeks.

Piglet fostering

Fostering was considered by the majority of herds to be a vital job – to which great time and attention to detail was applied, typically within the first 24 hours post-farrowing.

Having ensured piglets have received colostrum, herds then assessed not only the rearing capacity of sows in terms of functional teat numbers, but also teat shape and size in relation to piglet size, as well as presentation of the udder when suckling.

Herds either did minimal pig movements, by moving one or two of the larger pigs, or moved and mixed many pigs in order to have even-sized pigs in the litters. Gilts were “loaded” to carry 14 or 15 pigs for two weeks to ensure that all glands developed.

Nurse sows were created, usually via a two-step shunt; typically 20-25% of sows suckling in Denmark are nurse sows, enabling most to suckle 13 to 14 piglets through to weaning. This is one of the main reasons why the majority of Danish herds farrow weekly – so that nurse sows are always available.

The concluding point to reiterate is that the facilities used by these high-performance herds were very average; the distinguishing factor was the skill and attention to detail practised by the stock people involved.

Take part in AHDB Pork field trials

The AHDB Pork field trial that this survey helped to design is about optimising the potential of the small pig by using best practice in the farrowing house. The trial farms are implementing key practices and monitoring the impact so that, when the trial is complete next spring, some firm recommendations can be made to help producers make real improvements in farrowing house performance.

For more details on the trial programme, producers can contact Peter Dunne on 02476 478621 or Charlotte Evans on 02476 478627. Or visit: http://pork.ahdb.org.uk/research-innovation/field-trials/current-field-trials/