The reproductive performance of UK breeding herds has improved significantly in recent years. Statistics show that indoor breeding herds are now weaning 25.78 pigs per sow per year on average, while outdoor herds are producing 21.74 pigs per sow annually. Good results, but closer examination of Agrosoft-derived data shows there’s still scope for improvement. The top 10% of AHDB-recorded herds, both indoors and out, are weaning four more pigs per sow each year, demonstrating that UK dam lines are very capable of weaning 30-plus pigs per sow a year indoors, and at least 25 pigs outside.

But more impressive are the figures from the UK’s elite herds – indoor units ranked the best of the best. A number of these businesses consistently produce in excess of 14 pigs born alive per litter, while maintaining pre-weaning mortality rates well below 10% – some herds report 8.5% piglet mortality or less. A few are achieving 33 pigs weaned per sow annually, and are on target to wean 34 in the near future.

Although some hyper-prolific Danish-type dam lines will certainly feature among these top-flight herds – the data doesn’t specify genetic type – most of the genotypes used by this recorded population are likely to be of UK/British origin and so demonstrate that these genotypes are capable of exceptional performance. The productivity being achieved by herds in this segment is similar to that of the esteemed highly prolific Continental super sows they’re often compared with.

But prolific traits must be managed carefully. Although they do improve the odds of weaning more pigs, they can also bring challenges and put pressure on resources. In Denmark, for example, where many producers are on target to produce 35 pigs per sow per year within the next few years, pre-weaning mortality is around 20% or higher on many farms. The pig industry is beset by criticism surrounding piglet welfare, and some well-publicised, veterinary-led strategies are now in place to reduce piglet deaths by at least 2% by 2020.

This is a positive response that’s making an impact, but still means most herds will carry an 18 to 20% loss with every litter produced. By comparison, average piglet mortality for UK herds is 12.5%, which is commendable considering that 40% of the breeding sows are outdoors.

According to the sales manager at Rattlerow Farms, Simon Guise, increasing litter size certainly offers potential to increase herd productivity, but he doesn’t believe the Danish model fits our market per se.

“Yes, choosing a hyper-prolific strategy can and does work for some UK herds, but there are risks too, and I feel our industry’s structure would make it difficult to gain significant advantages without compromising some areas of piglet welfare and that’s important for an industry marketing its product on high welfare standards,” he says.

Implications

As a member of the NPA’s producer group, and chairman of the association’s Eastern Region, Simon is keen to highlight these issues. Although prolificacy is important, he says producers must consider all the implications that producing very high numbers born might have for the whole pig business. Pushing litter size beyond sustainable levels can present problems.

“By optimising the genetic potential we already have for reproductive performance – maintaining and improving piglet survival rates, and striving to reduce the number of empty days that currently exist within many herds – many UK herds could lift sow productivity to Continental levels. The potential is there, we just have to fine tune our management to harness it,” he adds.

Statistics from Rattlerow’s own commercial health status farms rank alongside the top 10% herds. Current performance on outdoor units is reaching more than 27 pigs reared per sow per year, with indoor herds rearing 30 pigs or more. Average numbers born alive are between 12.9 and 13.7 pigs a litter, and sows are producing around 2.35 litters a year. Pre-weaning mortality rates are consistently below 8%, with weaning weights at 8kg or more.

Optimising prolificacy is central to the company’s dam line programme, but a key objective is also to ensure their females can rear large litters of viable pigs and sustain these traits throughout their productive lives.

“Our Easy-To-Manage philosophy does work, and the consistently good results achieved by our own herds prove our dam lines are efficient, capable mothers that can produce plenty of good quality, uniform progeny both indoors and out,” says Simon. “By focusing on management techniques that can help maximise the potential that’s already available in UK breeding stock, more of our breeding herds could improve efficiency and reduce loss.”

Some UK herds are taking the hyper-prolific route and using Continental genetics successfully. They report exceptional performance with average numbers born alive at 16.5 piglets a litter with in excess of 32 pigs weaned per sow per year. However, pre-weaning mortality is much higher than the national average at about 18% – in line with Danish statistics.

“These herds are producing lots of piglets, which is commendable, but analysis shows that a herd producing 2.35 litters per sow a year, which is typical for UK production, could be losing at least 2.5 piglets from every litter produced, which is a concern,” adds Simon. “Do we really need to raise litter size any higher than current levels; will it help us improve breeding herd efficiency or will it create more wasted potential and become a contentious welfare issue as it has in Denmark.”

Misguided

Independent pig business consultant Stephen Hall believes the UK industry’s fixation with prolificacy must change. The continual selection for even higher numbers born is misguided, whereas concentrating on management strategies that would allow the dam lines they already have on their units to express their genetic potential would deliver better results.

“The genotypes available to UK farmers are very capable of outstanding reproductive performance,” he says. “They’re efficient and can provide what we need to meet ours and our customers’ needs without compromising animal welfare.”

A target of 32 pigs weaned per sow per year is a realistic objective for indoor herds, Stephen says, but the “Danish ideal” is not necessarily the way to achieve it.

“The UK pig industry works to different parameters. Pushing for more pigs born might suit some progressive businesses, but for most herds cutting out recycled loss and perpetual inefficiencies could generate more sustainable improvements to sow productivity,” he adds.

A better understanding of how repeated reproductive failure and the effects retaining old animals has on herd output would enable more pig businesses to control loss and increase productivity.

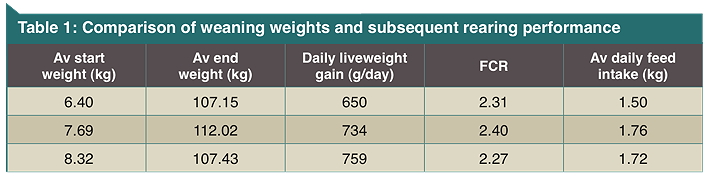

Weaner quality is another important factor producer overlook. Yet producing a consistent supply of strong, healthy, well-grown, four-week-old pigs does make a considerable difference to efficiency and subsequent profitability of a finishing business (see Table 1).

Using a benchmark of a 100kg weaned litter weight – be that 10 pigs weighing 10kg each or 13 pigs at 7.5kg – is a good guide, so producers must establish what specification works best for them.

“The emphasis should be on quality not quantity, which is how the UK differs from Denmark,” says Stephen. “The Danish market is fuelled by a lucrative weaner export trade, so numbers are important. Weaners are probably 1kg lighter there (Denmark) than they are here, which isn’t so important since the breeding farm rarely incurs the costs of raising these pigs to slaughter.”

UK herds tend to finish the bulk of their production, with most weaners usually contracted to supply an integrated, often wholly owned, supply chain – either as part of a complete breed-to-finish business or linked-finishing operation. The quality of weaners produced is or should be paramount as it’ll have a marked effect on the value of the pigmeat leaving the farm and business margins.

This fundamental difference is often underestimated when analysing the merits of hyper-prolificacy, and it’s another key reason why the “Danish model” doesn’t fit the UK.

Increasing sow productivity is important, but further advances in litter size aren’t the only means of “getting more from less”. A more foundational approach to management, using strategies aimed at harnessing more of the genetic potential that’s already on offer in UK herds, coupled with quality-focused weaned pig production, offers producers significant opportunities to raise efficiency while preserving, and possibly improving, their reputation for high-welfare production.