A cross-industry project in Northern Ireland has delivered some fantastic results in tackling PRRS across a group of participating farms, deservedly picking up the Innovation of the Year Award at last year’s National Pig Awards. HELEN BROTHWELL found out how it all works and what lessons can be learned for others

Farmer-led pig levy body, Pig Regen, supported by the European Innovation Partnership (EIP), has achieved truly impressive results through its PRRS Area Regional Control Programme in Northern Ireland.

This was duly recognised when it went on to win the Innovation of the Year Award at last year’s National Pig Awards.

Around half the farms that initially tested positive for the virus either achieved stability or became PRRS-negative during the three-year pilot scheme, which far exceeded expectations.

The group’s insights into running a multi-stakeholder initiative and the practical control of PRRS will have great value to others, including those currently developing plans for a regional PRRS control programme through the Government-funded Pig Health and Welfare Pathway in England.

Pig Regen formed a pig health technical group in 2016, which identified PRRS as a priority to control. Pig producer and Pig Regen chair Gary Anderson, along with operations manager Howard Tonks and DAERA pig adviser Dr Mark Hawe, were able to secure financial support for the ambitious cross-industry initiative from EIP in 2020. Their aim was PRRS control rather than elimination.

In spring 2020, they appointed industry consultant Dr Violet Wylie as the programme’s innovation broker, a vital coordinating role. Her key advice was: “You need someone to really care and lead consistently throughout the programme. They need to be like a dog with a bone, explaining, reminding and checking.”

The location for the pilot – within a 5km radius of Cookstown – is a pig-dense area. The view was that if it could work there, then it could work anywhere.

“The producers are enthusiastic and forward-thinking,” said Mark. “Many had worked together before, so there was some degree of trust between them already, but also a fair amount of apprehension.”

The 25 producers who took part all ran indoor breeding units, with herd sizes ranging from 20 to 700 sows. There were four specialist pig veterinary practices involved, with producers grouped accordingly into four smaller pods, so they could talk either within the pods or with the whole group. All vets and producers signed an agreement outlining how they would share information with each other.

Regular testing

Initial blood sampling and analysis provided a baseline of PRRS prevalence in the pilot region and was carried out a further two times on all 25 units, with a year between each sampling. They sequenced the virus to identify whether it was the vaccine or wild strain.

On farms where the wild strain was found to predominate, the local vet and farmer discussed vaccination and management options that could be implemented to control the infection.

Alongside the blood sampling, Boehringer Ingelheim’s Comprehensive On-line Management Biosecurity Tool (COMBAT) was used to provide a quantitative score for biosecurity on each farm, assessing 70 factors within four areas:

- Farm location – which couldn’t be changed, but if neighbouring herds are vaccinated and stable, it greatly reduces the risk of infection.

- Internal biosecurity – including pig and personnel flow.

- External biosecurity – covering anything coming in or out of the farm.

- Management – such as all-in/all-out systems, changing needles between litters when vaccinating and reducing contact between animals.

Dr Wylie then developed a specific action plan for each farm. “We chose actions that were practical and achievable, giving a good return on investment, to give producers confidence as early as possible,” she said.

“I worked closely with the vets, discussing the action plans for each farm and the vets ensured action was taken. COMBAT and blood sampling were carried out during the vets’ routine quarterly visits and if neither was needed, they could still give regular support with the action plans while on farm.”

Pig Health Mapping Tool

Data was managed and shared securely using the Pig Health Mapping Tool, a new software programme and app, purpose-built by a software developer at AFBI. It enabled COMBAT and blood test results to be shown visually on a map.

Each site was given a code number and its relative risk to other units was represented by a coloured circle, with the circle’s size and colour determined by disease status data. Vets could filter the data based on which units were vaccinated, whether their PRRS status was unknown, positive or clear and whether wild virus was present or not.

Vets were able to log in and see all the units in the group, having all agreed to share the information on their clients with the other practices in the group, but units remained anonymous.

“Making all the information available to vets helped them make informed decisions,” Dr Hawe explained.

Coordinated vaccination

To give the best chance of reducing the plume of PRRS virus in the area, the programme coordinated mass vaccination of sows across the group. To bring all farms in sync, half the producers had to move their vaccination timing, and a further six needed to put in an extra vaccination, which meant additional cost and labour for them. No piglets or growing pigs were vaccinated unless specifically required by the vet.

“Our aim was to vaccinate all breeding herds within a week of each other and, in reality, it was 10 to 14 days,” said Dr Wylie.

Text message prompts and reminders about vaccination were really appreciated by producers and vets. “The most important part was sticking consistently to the schedule, vaccinating every three months,” Mr Anderson said.

Practical changes on farm

He had begun to improve PRRS control on his pig unit before they began the regional programme. Although it was difficult, he feels it is still worth individual farmers giving it a go, even if their neighbours are not.

“If you can take control on your unit, it at least helps minimise the risk,” Mr Anderson said. “Plus, it ticks the boxes for control of other diseases as well.”

Many farms in the group had similar points in their action plans, covering both biosecurity and adjustments to vaccination programmes.

Regularly changing needles between litters or during blanket vaccinations is a simple, but very important improvement. “The cost is just pence, and it minimises the risk of passing on the virus from a positive to a negative pig,” said Mr Anderson.

He also highlighted the importance of flow of pigs and people around the unit. “Our pigs are mostly all-in, all-out but we also colour-coded each section of the unit and bought different coloured boilersuits, driving boards, paddles and buckets, and put coloured insulating tape around the top of the wellies to ensure staff and equipment stayed within a section.

We also have a footdip at the entrance to each area and insist staff use them and don’t forget to wash their hands,” he said.

Meanwhile, one big improvement for his external biosecurity was the introduction of bird, cat and rodent-proofing.

Pigs on Mr Anderson’s two breeding units were performing well but have been positive for the wild PRRS virus for a while. So, before the programme began, he had already moved from mass vaccination of sows every four months to every three months, due to the high viral load in the area.

He was previously struggling to control PRRS in his replacement gilt pool, as it is continuous flow. Gilts are now PRRS-negative, after adjusting their vaccination programme.

“Gilts are now vaccinated at weaning with all the other pigs and again before entering the gilt pool at 45kg. They then receive a further vaccination in the ‘gilt acclimatisation area’ at around 120kg.

“Finally, gilts receive a vaccination at the same time as the sows receive their mass vaccination, so they are all in sync. Controlling PRRS in the gilt pool in this way is key to controlling PRRS in your herd,” he said.

Health and performance results

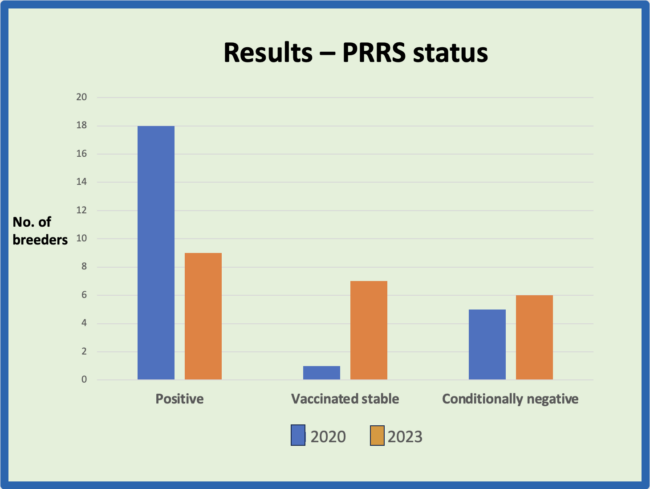

There were 18 units that tested positive for wild type PRRS virus at the start of the initiative – half of those became stable or PRRS-negative between 2020 and 2023.

Furthermore, on the units that were still positive, there were fewer positive samples per farm, showing the viral load was reduced.

This was achieved by working only with breeding units within the chosen area, which includes 60 units in total, with some rearing and finishing sites also receiving pigs from outside the area.

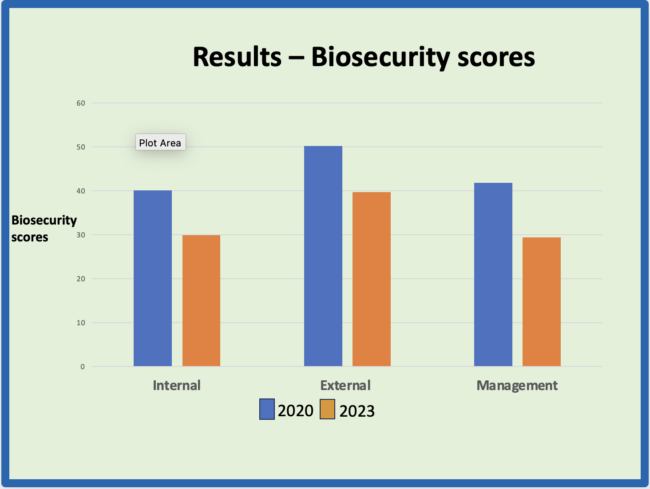

Biosecurity scores for internal, external and management factors all improved between the start and end of the programme, with the greatest improvement relating to internal and management factors.

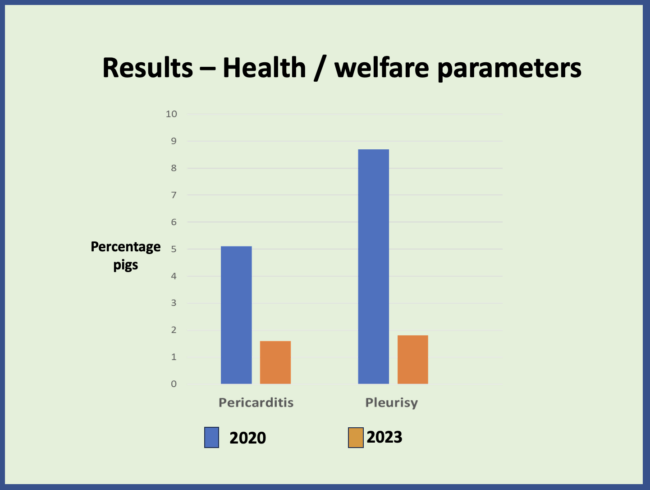

Data on heart and lung conditions in pig carcases from all the units that had improved PRRS status in the programme showed pericarditis reduced from an average of 5.1% to 1.6% of pigs and pleurisy reduced from 8.8% to 1.8%.

“The results may not all be down to this project, but improving management to reduce risk of PRRS will also reduce susceptibility to other diseases,” said Mr Anderson.

Performance data was collated for a small cohort of group members who had detailed recording systems, so it was only indicative. Sow conception rates improved very slightly and numbers of piglets born alive improved by an average of just over 5% between 2019 and 2023. Average carcase weight and back fat measurements across all 25 units in the group also improved by just over 1% and 4% respectively.

“The animals showed increased weight gain but without becoming fatter, which suggests their health was less compromised and that they were meeting more of their genetic potential,” said Dr Wylie, although, again, she acknowledged that not all the improvement may have been down to PRRS control.

Maintaining Commitment

Communication and cooperation were the two key pillars of the programme. The vets were very collaborative and the farmers were also prepared to make changes. All the farmers put in a great amount of work, which was fundamental to its success, Dr Wylie emphasised.

“There were a few farmers, initially, who were reluctant to take part, but they did so because their neighbours did,” she said. “Vets and advisers were crucial in encouraging participation. Then farmers became more and more interested, until they were asking us what was next.

“No-one wanted to be the one that let everyone else down.”

Before the start of the project, some of the group went on a trip to Denmark using a Farm Innovation Visits’ Scheme operated by DAERA.

“We spent a really interesting day hearing from three Danish vets and had the chance for a few beers and to talk to each other,” said Mr Anderson. “Everyone came away willing to give the programme a try.”

Dr Wylie was in regular, direct contact with producers and vets, providing both one-to-one support and reminders. Free blood sample analysis and time with the vet to discuss them were also valued by the producers, plus relevant information evenings and meetings.

Another motivator that grew over time was the proof that efforts were paying off. Gary and other farmers were able to tell the group ‘I’ve tried this and it works’, which inspired others who were not quite there yet to keep going.

Next steps

Dr Wylie and the team have begun to collect blood samples from herds they know don’t vaccinate piglets to get a baseline of wild virus levels across Northern Ireland. They are also expanding the pilot Cookstown group to cover a larger area.

Then there are a further three regions to be added, with the aim of one new one every three months. “We hope to get back to test each group a year after their last test, although this is quite ambitious,” she explained. “The same few vet practices cover the whole country and there may be bottlenecks due to their need to be pig clean for farm visits.”

In the longer term, a national programme could be run on an annual cycle, testing and reviewing one of the four regions every three months.

They have yet to confirm any outside funding for the national programme, but potential options are to use part of the levy gathered through Pig Regen with government support through research funding. The team would also like to work more closely with AFBI, which is looking at new types of flu on Northern Irish pig farms, due to the way PRRS and flu interact.