With the need to manage and measure emissions growing in importance, HELEN BROTHWELL looks at how current and future options to mitigate ammonia emissions on UK farms can work in practice, including the wide-ranging PigProGrAm project and other slurry management technologies that can bring additional productivity and financial benefits, as well as reducing emissions

Understanding how to manage and measure environmental emissions and pollutants, particularly ammonia, carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus, will only increase in importance for all pig producers as we move through 2024.

Many units are already operating under the Environmental Permitting Regulations (EPR), which currently includes routinely reporting ammonia emissions to the Environment Agency (EA), working towards the national target of reducing ammonia emissions by 16% by 2030.

EPR changes from 2024

The EA has provided an update on forthcoming changes to EPR requirements in 2024 and beyond:

Ammonia emission factor review: The EA commissioned an external project to inform and evidence updates to its standard ammonia emission factors, which permitted units use to calculate emissions. The report has now been finalised and there will be a short review and internal consultation period before the updated suite of emission factors is published.

Climate change adaptation: The new requirement is for all permitted farms to produce a climate change risk assessment by March 31, 2024. The EA is encouraging operators to produce this assessment over the next few months. There is a risk assessment template, including links to EA guidance, on the AHDB website.

N and P reporting: This reporting requirement will be extended to all permitted farms with retrospective reporting for the 2024 calendar year being required from January 2025. Thereafter, this will be an annual reporting requirement.

The EA will shortly release details of a new mass balance calculator tool and supporting information to help farmers to report annual livestock N & P excretion levels. Producers can either use the new mass balance tool or report excretions using results of slurry/manure sampling. The reporting tools for pigs and poultry will be on the AHDB website in 2024.

The exceptions to this are farms in the Wye catchment (all poultry), which will, again, be required to report annual livestock N & P excretions by February 29, 2024.

Templates and more details on how to comply with EPR are available at: https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/environmental-permitting-regulations.

Slurry storage and management

For all farms, not just permitted ones, the government’s Clean Air Strategy 2019 states that all slurry and digestate stores in England must be covered by 2027.

The slurry infrastructure grant scheme, detailed in the November edition of Pig World, is open to applications from pig producers. AHDB’s slurry wizard tool will help producers calculate slurry storage requirements to comply with regulations.

As well as covering slurry stores, using mild slurry acidification is currently the only other alternative slurry management technique officially recognised by the EA and other government agencies, Zanita Markham, AHDB projects and engagement relationship manager explained.

“Slurry cooling is also popular and can reduce carbon footprint via energy saving,” she said.

“Acidification and cooling both reduce emissions ‘at source’, which also bring benefits for the environment inside the building, and a number of commercial farms in the UK have invested in these in recent years.”

Slurry management technologies like this can bring additional productivity or financial benefits, as well as reduce emissions.

Farm case study: Slurry acifification

Lincolnshire Pork Co, winner of the Sustainable Farming Award at the 2023 National Pig Awards, runs a farrow-finish business, with two 750-sow breeding units, which rear pigs to 35kg, before transferring them to deep-straw finishing sites.

To help improve the environment inside the buildings for both pigs and stockpeople and reduce ammonia emissions, they included a slurry flushing and acidification system in a rebuild of their farrowing and nursery accommodation on both breeding units last year.

“It’s part of our aim to create a circular farming system, reducing ammonia emissions from pig production – in the pig house, the slurry store and in the field, as well as making better use of nutrients in the slurry applied to arable crops,” said Lincolnshire Pork Co’s Sam Ward.

The business used JHAgro/Agremeica to install the system, taking confidence from the firm’s wide experience in Denmark.

Mild acidification of slurry brings its pH down to less than 6, meaning ammonia is converted to ammonium which doesn’t evaporate. Acidification systems can reduce ammonia emissions by up to 67%.

Slurry from the pig housing is regularly removed from the shed via pipework to a processing tank, where small amounts of sulphuric acid are automatically added, according to pH sensor readings.

The majority of the acidified slurry moves to a storage tank, with some cycling back round to the pig housing to start a mild acidification process inside the housing when dung drops through the slats into the slurry.

“Ammonia monitors were fitted and linked to BarnReport Pro and showed a reduction in ammonia from 40ppm to 4ppm,” Sam explained. “There are also benefits for pig health, growth rates and reduced mortality. Although it is hward to measure these and to say how much is down to slurry acidification, nursery mortalities are down to 1.6% and 1.7% on the units.”

Most of the benefit is seen on the arable side of the business, with nutrients in both the slurry and soil becoming more available to the farm’s crops.

“Acidification increases the ammonium in the slurry, which is not as volatised as ammonia,” Sam added. “Also, the farm is on limestone soils which are pH 8, with no lime applied, and these high pH soils can lock up important crop nutrients, phosphate and magnesium.

“Applying the acidified slurry on the arable fields acidifies the root zone, making the nutrients in the soil more available to the arable crops, as well as increasing availability of nutrients in the slurry. It makes the system a perfect fit.”

The company has also made significant savings on sulphur fertiliser, displacing its sulphur requirements across its 1,100 hectares.

With staff retention an ongoing challenge, Sam said enabling staff to work on a modern unit in the best environment possible was another consideration.

The nursery and farrowing houses have a great atmosphere inside, with no obvious smell of ammonia.

The main running costs are the electricity for pumping and mixing, along with sulphuric acid to acidify the slurry.

Installation of slurry acidification systems can cost upwards of £400,000, said Zanita but grant funding may be an option. Costs were less when Lincolnshire Pork Co installed the system and they obtained 40% grant funding.

Farm case study: Slurry cooling

A North Yorkshire pig producer with 2000 sows opted to put in a slurry cooling system two years ago beneath new farrowing accommodation for 280 sows, opting for technology from Danish firm Klimadan.

“We saw there was potential for energy savings as well as reduction in ammonia emissions,” the producer explained. Based on Danish studies, cooling has been shown to reduce ammonia emissions by up to 75% and odours up to 15%.

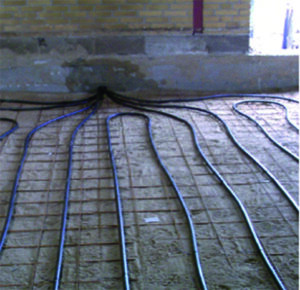

A circuit of pipework was installed in the concrete floor of the under-slat slurry stores. The surface of the slurry in the stores is cooled to 12°C or less by pumping cold water through heat exchange pumps and the heat is reused to heat help heat the building.

“There’s a noticeable improvement in the smell inside the buildings and hopefully in future we’ll be able to provide figures on ammonia reduction if the EA needs them,” said the producer.

“Our two heat exchange pumps are producing just shy of 4kW for every 1kW of electric used to power them, and I’d estimate we’re getting around 2.5kW to actually heat the building, taking into account losses along the pipes.”

The system was installed just in time to qualify for the Renewable Heat Incentive, so they receive a payment for producing the heat, although this is no longer available for new heat exchange systems.

In this case, two existing biomass boilers on the unit provide the heat for 200 farrowing places in the building, with the cooling system heating the other 80 pens.

“This balance is simply down to the RHI’s system which means we’re currently better off financially to claim the majority of the RHI payment on the biomass,” the producer explained.

“In the longer term there might not be RHI on biomass, so we have the heat pumps in place as back-up, which they already provide if the biomass boilers go down.”

The unit also has solar panels to help power the heat pumps. The total investment was £35,000, with the producer providing their own labour, but slurry cooling can cost up to £50,000.

“Make sure you deal with a company who gives you confidence as it’s a big investment,” he advised. “We went with Klimadan who had a lot of experience installing the system on farms in Europe.”

There is a basic annual service for the pumps and the only running cost is the electric. “The manufacturer’s expected lifespan is 20 years and I’d estimate we’d get a return on investment in three years with the RHI, or five years without,” said the producer. “We were already using the biomass boilers so there was no energy saving but, if you were moving from electricity, the saving would be around £1000 per month.”

They are currently installing another cooling system in additional farrowing accommodation with 96 places.

“If you’re putting up a new building, I think it’s worth at least laying the pipes for a cooling system in the flooring, even if you don’t invest in the heat pumps until later,” the producer said.

Farm case study: Green fuel from slurry

The PigProGrAm is a major trial aiming to reduce ammonia emissions and explore the feasibility of using the ammonia to produce hydrogen – a zero-carbon fuel – to reduce the carbon footprint of pig production, alongside the use of co-products in feed.

The project’s full title is ‘Developing a Circular Economy for UK Pig Production Through Green Ammonia Harvesting’ and it has received £600,000 of funding under the Government’s Farming Innovation Pathway collaboration between Defra and UKRI.

Delivery partners include AHDB, Beta Technology, Duynie Feed UK, the University of Leeds, Membracon and an indoor pig producer.

“If ammonia from pig slurry can ultimately be converted to ‘green’ hydrogen and used to fuel tractors or cars, it changes from an environmental problem to a solution, which can help reduce carbon emissions in farming and beyond,” said Zanita.

The main equipment in the trial, on a North Yorkshire finisher unit, is a downflow gas contactor (DGC), commonly used in water treatment plants. This releases the ammonia from the liquid fraction of the slurry and changes the ammonia from liquid to gas form.

“We are also using best practice slurry management techniques on the farm including a pit recharge system and flushing and separating the slurry every 48 hours,” Zanita explained.

There are three main areas of data collection, with full results set to be published in Pig World soon:

1) Levels of ammonia it is possible to extract from the separated slurry via the DGC process.

2) Monitoring of ammonia emissions leaving the shed.

3) A full lifecycle analysis to measure reduction in carbon footprint, taking into account co-product feed, animal performance and slurry management.

“The next stage would be to investigate the potential for hydrogen production through electrolysis of the harvested ammonia, which is already a recognised process,” Zanita said.

“If more funding was granted, we would look to test the ammonia-rich product on farm for its electrolysis potential