Kenniford Farm has made huge strides after changing its weaning strategy. Helen Brothwell discovered what continues to drive the 2018 Indoor Pig Producer of the Year when she visited the Devon farm

A move to weaning piglets at 35 days instead of 28 has improved piglet performance and enabled Devon producer Andrew Freemantle to achieve much greater profitability from his finisher pigs.

But there is more driving the National Pig Awards Indoor Pig Producer of the Year in 2018 than profitability alone. A chat with Andrew and his pig manager, Grant Morrow, showed there is pride in their work, attention to detail and a desire to try new things to keep improving.

It’s no surprise the team are achieving such impressive results in both pig production and Andrew’s catering butchery enterprise. Grant and his wife, Jo, also won Stockman of the Year at the 2014 National Pig Awards, and this summer Andrew’s team produced the champion sausage

in the Taste of the West awards. Andrew has run the 340-sow farrow-to-finish unit, breeding all their own replacements, at Kenniford Farm, located near Exeter, for 25 years.

They have made a gradual transition from weaning piglets at 28 days to 35 days during the past two years; moving from weekly farrowing to a two-week batch system with 30 sows farrowing each batch.

“We’ve found it’s the most efficient way to achieve our target numbers and weights through to finishing,” Andrew said. “We have a finite number of finisher spaces and weeks available for the 400 pigs that we finish per batch.”

The suggestion to add on a week to the weaning age came from Paul Wright of Checkmate, who assessed the feasibility for their system. “We look at our data a lot and it was showing us that the heaviest pigs at weaning were nearly always making the greatest weight gains through to finishing,” Andrew explained.

“We’ve found an extra 2kg at weaning can lead to an extra 10kg at slaughter in the same number of weeks, and that’s what the extra week in the farrowing house gives us.”

WEEK FIVE BENEFITS

“The most important week of a pig’s life is that fifth week. The gut is more mature at 35 days, so it’s a stronger, heavier pig at weaning with an extra week to adjust from its liquid milk diet to the solid creep. We’re now using zero antibiotics, and half the zinc used when weaning at four weeks.”

The switch to the new system means that they’re now weaning 30 sows with piglets typically averaging 9kg, whereas previously they weaned 33 sows but with weaners weighing only 7kg.

While Red Tractor doesn’t allow sows to be in farrowing crates for more than 35 days (up to seven days pre-farrow and 28 days after), this isn’t an issue for Andrew as his pigs are moved to the free-access pens for the last two weeks before weaning.

“Pigs are growing at an average 810g/ day from wean to finish, with 600g/day in the nursery and 1,100g/day in the finishers. Pig manager Grant said: “We’re typically producing 5kg more per finished pig than before, with an average deadweight of 80kg.

“The finisher herd is where the potential for earning extra money is – provided the finisher unit is full and efficient. If you get a strong enough piglet in there at the start and manage the nursery and finisher stages well, the improvements in growth and feed efficiency can be exponential. Nine years ago, we were selling 8,000 pigs at 65kg deadweight and now it’s 9,500 at 82kg, from the same-sized herd of 340 sows.”

They sell the majority of pigs through Thames Valley Cambac, which takes the larger pigs at an average 88kg deadweight, plus a few light pigs to a large farm shop and a butchery chain. The other 14% (20 to 35 per week) are self-supplied through the Kenniford Farm catering butchery business. It helps to have their own outlet that can take any slower growers as porkers, so pigs aren’t kept for longer to reach a higher finished weight, eating additional food.

The creep feed is a standard specification and is offered from four days to start getting the gut used to it. Intake is around 1kg per piglet, which, combined with the sow’s milk, is enough to ensure good growth and a more mature gut before weaning at five weeks.

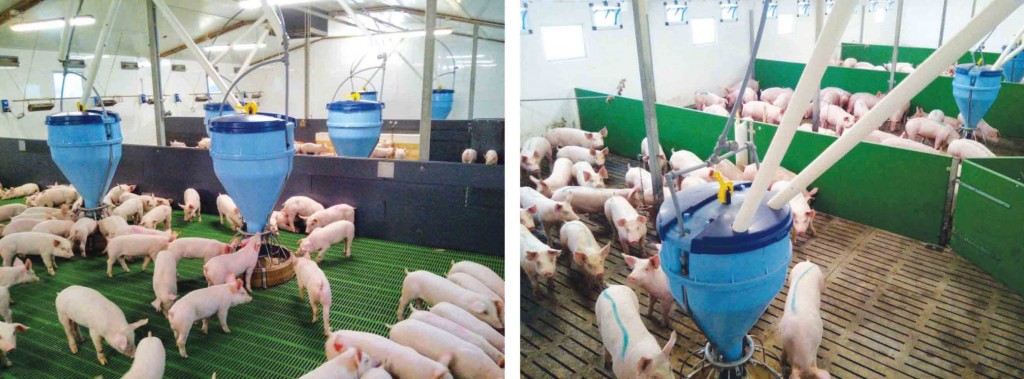

They then feed creep (at 1kg per pig) and a link diet priced at around £330 a tonne, which Harbro mixes on farm with a mobile mixer wagon. Ingredients include biscuit, fishmeal and barley and it’s fed via an auger system in the nursery, so it’s simple and low on labour. Following that, there are one grower and two finisher rations.

All piglets are weighed in groups at weaning and again on leaving the nursery. When weaning at four weeks, their average transfer weight when moved from nursery to finishing was between 32 and 42kg (at 102 days old). Pigs weaned at five weeks are now averaging 45 to 55kg at the same age.

It’s a fully slatted Red Tractor-approved ARM finishing unit, built three years ago, within the existing footprint of the straw- based unit that was there.

All these changes were driven by a significant increase in numbers of pigs produced, which the team achieved through its efforts in the breeding herd. The farm used the Hermitage BLUP system to record and select gilts, focusing on improving numbers born alive and, over five years, the average figure has risen from 11 to 15.5. They selected the maternal line boars based on birth and weaning weight. Andrew said: “We reached a point where we didn’t want to be chasing numbers any higher and we focused on how to capitalise on the extra piglets through the finishing system.”

To maintain the number of piglets weaned and make the 35-day weaning system work, careful management at every stage of production is essential. For example, Grant stressed the importance of keeping sows in the right condition: “Sows are fed a specific lactation ration in the farrowing house to make sure their needs are met right up to weaning at five weeks. You can’t wean thin sows – otherwise you jeopardise performance in future litters,” he said.

Going back further in the production cycle, gilt management is the basis for everything. Like with the weaned piglets, the emphasis is on putting time and effort into preparation. “Gilts are fed a gilt-rearer ration from 45kg and, from 180 days, we give them contact with vasectomised boards to make sure they are cycling properly, ready for service at 240 days,” Grant added.

“If you don’t make sure the gilts are fully mature and in good condition before first service, it’s almost impossible to recover performance in later parities. We don’t ever see a second litter drop.”

Gilts average 14.4 piglets born alive and go on to produce around 16 born alive in the most productive parities of three, four and five. Sow retention rates are good with an average parity of 2.9.

Attention to detail in the farrowing house is really important to their success. They have employed a Harper graduate who is focused on the farrowing house to ensure adequate colostrum intake and to manage the extensive shunt fostering system.

Their pre-weaning mortality is around 12% with an average number born alive of 15.4 and they’re weaning 13.3 pigs per litter. “We do a lot of shunt fostering to achieve this. We kept 54 of our original free- access Solari pens, which provide the extra farrowing house spaces needed for foster sows.

Sows move to the free-access pens after 20 days and stay there for the last 15 days up to weaning. It’s an extra move for them and more pen cleaning for us, but both the sows and piglets do really well.

“Each time we wean, we keep back any smalls that are 7kg or less and put them on a sow who has just been weaned and still has plenty of milk. We know if we put a 6kg piglet into the finishing unit, they aren’t going to make 88kg in our 19-week timeframe.”

The costs of keeping litters a week longer in the farrowing house are minimal for the business. “It’s the same amount of work and the same asset for us,” Andrew said.

COST-EFFECTIVE

“We already had plenty of farrowing spaces, with the Solari pens still in use. So, when we were deciding how we could get heavier pigs out of our system, we went for 32 extra farrowing places and the lease of two more nursery cabins, instead of 400 finisher places.

“Farmers might not want to increase their farrowing index, but the growth benefits from wean to finish have made it much more cost effective for us overall.”

“Simply switching to 35-day weaning is not a guarantee of success, though,” Andrew said. “It’s no cover up for things such as poor pen design or ventilation. All aspects

of pig management have to be right.

“For example, we had a Strep. suis issue just after weaning, which was triggered by a bit of extra stress, as we hadn’t got enough drinker spaces to match the feeding and drinking patterns of the genetics of the pigs going through. We provided more drinking space and the problem has now reduced.”

Looking to the future, Andrew is uncertain about exactly where to take the business next. “The turnover is similar for both the pig unit and the catering, and it feels nicely balanced,” he said. “I’m aware that a diversification can sometimes outgrow a business and then fall down again. It’s working well for us at the moment as we can maintain the artisan nature of our butchery products and the price premium that comes with it. We hand tie all our sausages, for example.”

However, Andrew is certainly not standing still. He continually reviews how the business is performing and is always open to making changes or seizing new opportunities. The latest catering venture has been to take on a fish-and-chip stand on the seafront at Exmouth, where, of course, they also sell their sausages.

In January, they closed their farm shop as it wasn’t bringing in enough custom to justify the running costs, as the farm is not close enough to a major road. They still sell to a couple of other retail outlets, but are focusing on catering. “We’ve now got four all-year-round catering kiosks at Mole Valley Farmers shops and we’ve become more selective about which events we go to,” he added.

Even so, Andrew and his family are on the road for much of the summer – between May and September, they take their mobile catering stand to 30 events.

These typically include the main country shows, music festivals and Christmas markets. “It’s long hours so I tend to see it as my hobby! Otherwise, you might struggle to feel you had any work-life balance.”

TEAM EFFORT

Back on the pig unit, they would like to invest in specific gilt rearing accommodation if possible, to avoid moving breeding gilts off-site. They currently go to the finishing site and come back again.

“Another thing we’d like is to have a good tidy-up and do the bits of maintenance and paintwork that get pushed down the priority list when prices are tighter or you’re focusing on new systems.

“Also, at the moment we’re weaning 400 pigs at 9kg and it would be good to see if we can make that 10kg. Perhaps we could streamline the fostering system further or look at a different style of accommodation.

“Genetics wise, we’re trialling the PIC 800 Duroc – for just a month’s worth of services. We’re looking into whether we can improve taste and eating quality, given our farm-to- plate business.”

Whatever developments Andrew invests in next, they will be based on a close look at the figures and a clear sense of how they fit in with, and improve, the overall business.

And it will be a team effort. After winning the award, Andrew’s first thoughts were for his team. “They are the ones that put the hard work in. This award is for Jo, Grant, John, Ray and James. It’s nice to have recognition for the things we have implemented and it’s heart-warming to know people appreciate what we do,” he said.