A four-year research project has shown that using a co-product from bioethanol production can be used as an alternative protein to feed pigs.

The Defra-funded ENBBIO Link programme involved 25 industry and academic partners to examine how distillers’ dried grain with solubles (DDGS) would work for pig and poultry producers.

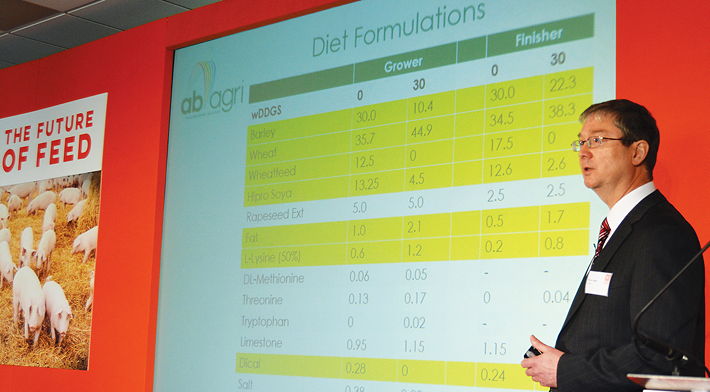

Results from the study show that DDGS could comprise up to 30% of a pelleted ration for growing and finishing pigs, but that further work needed to be done to improve the quality of the diet. During trials, pigs fed with DDGS displayed reduced levels of digestibility of the essential amino acid lysine.

About 80% of animal protein for UK farming is imported, with half being soybean meal from South America. But a new, British-made alternative is already in use on native livestock and dairy farms, with Teeside bioethanol plant Vivergo producing more than 500,000t of animal feed for farmers in 2014.

However, until now, little research had been carried out in the UK into how DDGS performs when consumed by mono-gastrics. Trials began in the poultry sector with broilers and laying hens fed a diet containing up to 18% DDGS to measure feed conversion ratios, growth rates and nitrogen digestion. The broiler trial showed no difference in liveweight gain between the control and the test flock, and even showed a better feed conversion ratio. But the overall cost of the DDGS diet was higher due to the need to include more pure amino acids to balance the feed.

A laying flock trial conducted by Noble Foods also showed positive results and concluded that feeding hens wheat DDGS at 7.5% was practical and had no negative impact on egg quality or productivity.

Pig trials

Research then moved on to the pig sector, where graded levels of DDGS – ranging from zero to 300g/kg – were included in the pigs’ pelleted ration. The trials were carried out at Nottingham University on penned growing and finishing boars, while at Harper Adams University mixed sexes were group housed. Growing pigs weighed between 35kg and 65kg, and finishers between 60kg and 105kg at both sites.

The trial showed no difference in performance or kill-out percentages, but the issue of lysine digestibility was again apparent. Professor Julian Wiseman from Nottingham University said the problem could be linked to grain drying carried out as part of the bioethanol production process.

“Lysine is an essential part of any pig or chicken diet – it must be there to get adequate performance and carcase quality,” he said. “The level of lysine actually being absorbed is lower than it needs to be and we suspect it’s because in the production of DDGS there’s a drying process and high temperatures could affect the digestible levels of lysine in the feed.

“We got a very similar pattern of data as with the chicken work. We were getting between 65% and 80% digestible amino acid, except with lysine we were down to 30%.”

AB Agri pig nutritionist Steve Jagger said that the university trials had produced some encouraging results and that up to 300g/kg of wheat DDGS could be used in grower and finisher diets. But he added that cost, and having an accurate digestibility value for the diet, was important to producers.

“The financial value of using wheat DDGS is affected by the stage of production, the cost of raw materials and amino acid digestibility,” he said. “But it’s a viable alternative protein source for pigs.”

In order to test the findings of the university research on a commercial scale, Jen Waters from Tulip oversaw a continuation of the work. She assessed the on-farm performance, slaughter characteristics and meat quality to ensure the alternative protein didn’t have a negative impact on the end product.

“What I’m interested in is what happens in the abattoir, and from my perspective there was no effect on farm performance, slaughter characteristics or meat quality, so it worked on a large scale.

“We can feed wheat DDGS at up to 30%, and potentially we could push it a bit further if it was cost effective.”

Creating the co-product

The Vivergo plant uses about 1.1 million tonnes of feed wheat per year, sourced from local farmers in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. The lower-grade feed wheat used is ideal for fermentation due to its high starch content.

The feed-grade wheat is milled before water is added and heated to form a thick, porridge-like mix. This is then moved on to the fermentation tank before being pumped into the distillery, where the alcohol is separated from the fibre and protein. The protein and fibre is then pressed and dried, before being pelleted into feed.

Vivergo’s Mark Chesworth said the issue of lysine digestibility was not something that the company had encountered in the process of selling DDGS to the livestock sector, but that it was an addressable issue.

“In terms of to what level of moisture we dry prior to pelleting that can be amended,” he said. “It hasn’t raised its head in livestock, but that’s something we can look at because it’s about finding a balance between what’s right for the animal and what’s practical from an operational perspective when we produce bioethanol.

“We’re new to this market, production was only ramped up in 2014, so we’re still finding the right balance.”

Mr Chesworth added that if the issues with the pig and poultry feed sectors could be addressed, the success of the co-product in the sectors would come down to cost.

“Grain markets will ultimately influence the price of feed, and there are other factors too such as the cost of soya, energy, oil and fuel,” he said. “They all have an influence.

“In terms of the ruminant sector we believe that we’re competitive with soya on price, but it sounds like on the pig and poultry sectors it might be a bit tighter.”