An early warning system to detect when a tail biting outbreak is brewing could be set to go commercial. Colin Ley reports

The search for a tail biting early warning system equipped to send pre-outbreak alerts to the stockman’s phone is gaining momentum as part of a three-year research project called TailTech.

Following on from a successful 3D tails trial run by researchers at the Scottish Rural College (SRUC) in Edinburgh, the new programme involves pigs on nine commercial farms with the aim of producing a prototype alert system within the next 12 months.

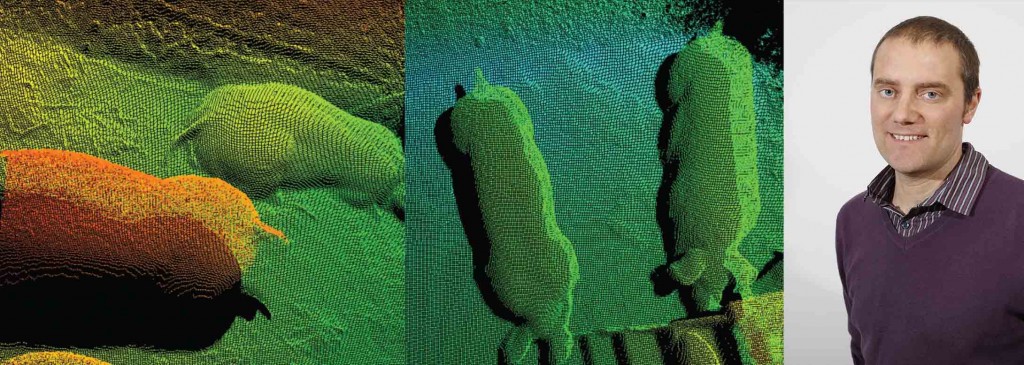

The original 3D programme, also headed by SRUC, explored the use of 3D cameras to monitor high risk tail biters by observing changes in tail posture.

Carried out on a single research farm in Scotland, the theory behind the programme was to assess whether pigs holding their tails down against their body was a reliable early indication of an imminent tail biting outbreak. The conclusion, reached in April 2018, was that an increase in pigs with low tails is a good indication that an outbreak is brewing – at least they are in high risk circumstances.

SRUC research leader Dr Rick D’Eath (right)

The single-farm focus of 3D tails, plus the use of undocked pigs under high-risk conditions for the trial, left many questions unanswered – which prompted the launch of TailTech just under a year ago.

Due to run until mid-2021, this new project is designed to test the low tail theory across a wide range of farm type and commercial conditions, with the added value aim of producing a prototype unit as a potential next step towards giving farmers a reliable early warning system to help them control tail biting before it gets out of hand.

“The 3D project was extremely successful as a ‘proof of concept’ that low tails indicate a rising risk that a tail biting outbreak is about to begin,” SRUC research leader Dr Rick D’Eath told Pig World.

“It also proved the success of using a 3D machine vison algorithm to monitor at-risk pigs and helped us to establish that low tails were a factor in pens where tail biting subsequently occurred but not in pens which housed non-outbreak groups.

“Our conclusion was that there is a distinct correlation between tail damage and low tails. Pretty much everything we trialled worked as expected. That doesn’t often happen in science.”

From that base, the next challenge was to broaden the trial by moving it into a fully commercial environment.

“Since April last year we’ve installed monitoring cameras on nine commercial farms, with researchers being sent to score tails on each unit,” said Dr D’Eath.

“Apart from that, we’re basically letting everything happen as it happens. We’re not influencing the risk of biting, nor trying to make it better or worse, just concentrating on trying to observe normal management on a range of different farms.”

While researchers will need some biting to occur to get a chance to test their monitoring efficiency, this is an opportunity to reflect real UK pig farming in all its diversity.

In that context, the nine trial farms include pigs with docked and undocked tails and farms where pigs are kept in large groups in barns with deep straw, through to units in which pigs are kept in smaller groups on slats.

Some units are Freedom Foods- accredited, with others representing typical indoor production systems commonly seen across the UK.

“We also have a trial running on a JSR breeding company unit which features EID, which was already installed,” said Dr D’Eath. “This is particularly interesting for us in that our monitoring to date has recorded low tail activity in all the pigs in a pen without being able to identify individual animals.

“Monitoring at a group level, of course, will include times when we’ve been recording one pig that just keeps crossing in front of the camera. With EID in place we’ll be able to take our monitoring to an individual pig level, allowing us to be much more precise in assessing what’s actually happening in the run-up to a biting outbreak.

“What we suspect happens ahead of an outbreak is that there is an early biter and an early victim, and that victim starts holding its tail down quite a lot of the time in response to having been nibbled at. The others in the pen might remain quite normal at this point, however, which makes low tail activity difficult to detect at a group level.

“One pig holding its tail down within a 30-pig group is only about a 3% change of behaviour. In such circumstances detection only really kicks in when others in the group also start to lower their tails. If our system could detect a significant change in a single pig, however, then a stockman could be alerted to a potential tail biting outbreak earlier.”

In seeking to develop a prototype early warning system that farmers can use commercially, the research team at SRUC are keenly aware that whatever they create can only be launched once and that they can’t afford too many teething problems.

“If the system sends an alert to the farmer but when he looks at the pigs he sees no problems, then he’ll just switch it off,” said Dr D’Eath. “The unit will then be discredited before it has a chance to work. We have to strike the right balance been genuine alerts and false alarms.”

Doing that will mean setting alert levels that reflect a genuine rise on pre-outbreak risk without over-reacting to minor shifts in behaviour.

“Through TailTech we’ve starting to have a lot of available data from a lot of very different farms,” said Dr D’Eath.

“We’re getting a better idea of how tail posture varies between groups, building on our 3D findings, which also showed major differences between groups.

“In designing an early warning system, we won’t just say that when low tails in a group of pigs goes above some fixed threshold that it’s time to phone the farmer. It’s more likely we’ll check how this pen goes for a week or two, after a new batch goes in, and then set a baseline low tail posture for that pen, with the farmer only needing to be phoned if the pen goes above its own baseline by some amount.

“That’s the sort of stuff we need to get right, however, if the results of the 3D project and what we’re now discovering through TailTech is to have a real on-farm impact.”

While what to do once an outbreak is deemed to be about to happen isn’t really part of the TailTech project, the SRUC approach during the 3D trial involved acting as rapidly as possible to prevent injuries occurring.

“Our work was Home Office-regulated, of course, and focused on studying what happens prior to tail biting,” said Dr D’Eath. “Once an outbreak began we had no interest in allowing it to continue, just like any commercial farmer.

“We added shredded paper, balls, traffic cones and the like to pens to distract pigs and removed both identified biters and badly bitten victims to isolation pens. We didn’t quantify the best method in the midst of this, however, but just threw everything we could think of at it to reduce the outbreak.”

Helping farmers spot the early signs of tail biting long before major control activity becomes, necessary remains the core objective of TailTech.

The target for the final two years of the programme is to build a prototype over the next 12 months and then test it thoroughly on a selected farm during the final 12 months.