Professor Sandra Edwards, for many years a hugely influential figure, globally, in using science to improve pig welfare, has written a book on the subject. Helen Brothwell sought her views on on of the big welfare issues of the day for the latest edition of Pig World magazine.

There are still questions to answer, but the pig industry has come a long way in understanding and improving pig welfare, according to Professor Sandra Edwards, who has brought together all the latest knowledge from renowned colleagues around the world in a new book on the subject.

“Our understanding of how the pig perceives life and why it behaves in certain ways has advanced enormously,” said Prof Edwards, who has spent decades developing science-based solutions, always keeping in mind the practical and economic realities of pig production.

Prof Edwards, a hugely influential figure in the field of pig welfare on a global scale with more than 200 publications, retired as Chair of Agriculture at Newcastle the University in 2017, but has continued her interest in the subject, culminating in the book, Understanding the behaviour and improving the welfare of pigs, which covers all aspects of an increasingly hot topic for pig producers.

She believes new technology will only help driver further improvement. “Precision farming technology means our ability to understand pig behaviour and welfare will grow exponentially, with huge amounts of data being recorded in real time. It really has revolutionised science,” she said.

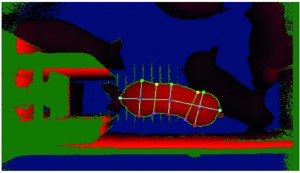

Researchers have highlighted the importance of moving from science to on-farm solutions, integrating key welfare indicators and encouraging wider use of camera sensors and image analysis, which can automatically monitor multiple animals’ behaviour.

Precision technologies will also help with a question which goes beyond simply avoiding and solving problems. That is, to what extent can we understand what the pig is feeling and therefore offer a better life and improved wellbeing?

“It’s difficult to define what we mean by emotions and mental states of the pig and there are also a wide variety of possible ways we could measure it, from vocalisation to facial expressions, so it’s still early days for science in this area,” Prof Edwards added.

Consumer perceptions

Consumer opinion is a complex influence on pig welfare developments, with a great divergence of views. “Some people are only comfortable with pigs kept in fields, some with pigs on straw and others who are just interested in pork that they can afford,” Prof Edwards said.

“While farmers look at whether pigs are healthy, contented and growing well, the public tends to focus more on the opportunities given to the pig, rather than the indicators the pig provides.

“The effect of social media is huge. It can give a misleading impression that something is the norm when it’s not – a lot of social media influencers have good intentions but are ill-informed.

“Also, while influencers might affect political voice, there’s still a disconnect between people’s ethical beliefs and their buying choices at the shop.

“The average member of the public doesn’t have a detailed understanding of animal welfare so it’s important for organisations to move forward together – there has been some good cooperation between government, NGOs and the pig industry over the years in the UK,” said Prof Edwards.

There has been a positive shift towards outcomes or animal-based measures of pig welfare, rather than inputs and the environment provided. Developing systems of animal-based assessment on farm which are quick to use, while still providing meaningful information, is an ongoing priority. Precision techniques will help, with a shift towards more automated recording of welfare indicators.

Free farrowing

The UK pig industry could soon be facing a new legal requirement to switch from conventional to freedom farrowing systems. Prof Edwards said it was important for producers to seek information about what might suit their unit.

Science shows that, when the sow is an active participant in her own environment, she will fulfil her own needs and also contribute to those of others. Maximising piglet survival increases her biological fitness, while satisfying the main needs of the piglets and farmer. It’s important, though, that new system design enables stockpeople to assist safely without putting any further constraints on sow welfare.

“It currently remains down to the individual farmer to choose what type of system to invest in, based on their own situation and longer-term aims.

“Free farrowing is something you can’t write a blueprint for, with different genetics and environments just two factors that vary between farms; free farrowing requires a high level of planning and day-to-day management for it to meet all aims. The government needs to incentivise pioneering producers to help build up practical trial data on the day-to-day details.

“It can take a number of batches of pigs to get used to it and get it right. As a producer, if you try something new and it doesn’t go as hoped, you can feel you’re not doing right by the pigs,” Prof Edwards said.

“Producers should seek out as much information as possible beforehand and talk to other producers who have already done it. There has to be a strong belief in order to get beyond the teething troubles and ideally some financial assistance to help bridge any economic hiatus during transition to a new system.”

Tail biting and docking

The main aim should be to continue to find ways to avoid invasive procedures like tail docking wherever possible, by providing an environment which best meets the pig’s behavioural needs. Genetic selection can also help, Prof Edwards added.

“The solution is getting all aspects of management right for your particular farm. In finishers, it might help to give a bit more space – depending on current stocking levels – or provide some straw or different enrichment and a longer feed trough. It could also be to do with temperature, ventilation, diet, or health.”

Furthering understanding of pigs’ perception of pain and what can be done to manage it is also important, particularly around issues such as castration and tail docking.

“Interesting new research is looking at both immediate pain and evidence of longer-term pain, including phantom pain. We don’t yet know for sure whether an older tail-docked pig might feel pain where its tail end used to be. Scientists also want to understand the balance of consequences between being tail docked and being tail bitten.”

Genetics

There has been a shift in emphasis on genetic selection, towards behaviour as well as growth. While these traits don’t have the same genetic basis, geneticists today are able to select for them simultaneously, with the help of very large data sets and sophisticated analytics.

“There’s a discussion about genetic predisposition of individuals towards aggression and also about social genetics. This considers the direct effect of genetics on each individual pig along with the indirect impact of the other pigs in the pen and, ultimately, the growth performance of the whole group.”

Early life

Non-genetic social factors in the early life of the pig are also known to influence its behaviour and robustness throughout life. “Piglets sharing the same environment early in life develop common social skills and initial research suggests that the way the piglet is kept in the farrowing house might affect its likelihood of tail biting in the future. Stress on the mother in pregnancy can also affect her piglets’ susceptibility to stress later on, with further research on this underway.

“Recent research suggests that, if there is greater diversity of enrichment in early life, pigs will be less likely to tail bite and more likely to use enrichment when they’re older.

“We also see that outdoor piglets generally transition through weaning more easily, as they are better adapted to changing environments. Gut microflora tends to be better developed too.”

Microflora and health

This links to another area of research, investigating how the balance of gut microflora can influence pig behaviour, as well as immunity. Studies show that the pig’s genotype influences the development of the microbiota and there is a possibility that pigs who tail bite have a different gut microbiota composition than pigs that do not.

“The interactions between health and welfare are hugely important. If pigs have an underlying health issue such as stomach ulcers, for example, resulting pains can influence aggression. Knowing this means that we can change the nutrition or other factors to help solve it.

“Getting to the root of any welfare problem is usually the biggest challenge – if we know the problem, we can often find a solution.”

Discount offer for Pig World readers

Copies of Understanding the behaviour and improving the welfare of pigs can be obtained in print and digital formats costing £150/$195/€180/C$255 from www.bdspublishing.com. Pig World readers can benefit from 20% off the book. Enter code PIGWLD20 at checkout via the Burleigh Dodds website to re-ceive this discount.