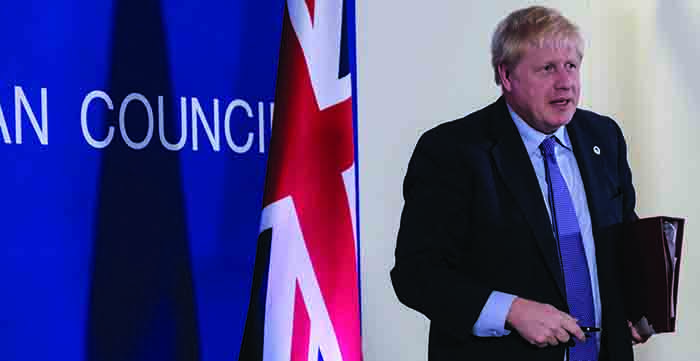

Boris Johnson’s overwhelming election victory means we enter 2020 with some short-term clarity about where Brexit is going. But many longer-term questions remain. Alistair Driver reports

If 2019 was the year the UK descended into a mire of political chaos the like of which we had never seen before, 2020 at least offers the prospect of some stability, albeit with one very big catch.

Boris Johnson’s overwhelming election victory was, like it or not, a resounding endorsement from the electorate of his repeated promise to ‘Get Brexit Done’ and also of the Prime Minister, himself, despite, or perhaps because of, all the controversies that swirl around him.

The vanquishing of Labour and the Liberal Democrats, leaving both parties in disarray, means Mr Johnson’s Conservatives enter 2020 in great spirits, with a majority of 80 and a mandate to deliver Brexit in his image.

In the week before Christmas, MPs backed the Prime Minister’s Brexit plan – a phrase that had not been uttered for a very long time. They voted by 358 votes to 234, a majority of 124, in favour of the EU (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill, sending it on its way for further parliamentary scrutiny, likely to culminate in our departure from the EU, on time, on January 31. This time, it really should happen.

Mr Johnson said the country was now ‘one step closer to getting Brexit done’ and that we can move forward from the ‘sorry story of the last three years’. The vote paves the way for an ‘ambitious free trade deal’ with the EU, he added.

Under the deal Mr Johnson agreed with the EU prior to the election, the likely January 31 departure will set in motion a transition period until the end of 2020, during which little will change, with the UK remaining in the customs union and single market.

This, at least, delivers some welcome certainty for the industry, in contrast to the project fear-driven crippling uncertainty that characterised the run up to the March 31 and October 31, 2019 ‘deadlines’.

That had numerous unwanted effects, including delayed meat shipments because of tariff uncertainty, the unnecessary stockpiling of pork products by processors, which subsequently held prices back when they should have been rising, and lingering questions about the viability of future EU trade and the availability of inputs and labour. This time it should be much more straightforward, providing issues like third country export access are quickly tied up.

NO DEAL SAGA

But the whole no deal saga could soon come round again because Mr Johnson has gone a step further with the Bill, adding a new clause legally prohibiting the Government from extending the transition period beyond December 31, 2020.

Designed to focus minds on getting the next stage done quickly, it means that in order to prevent the UK reverting to damaging no deal WTO trading terms in less than 12 months from now, the UK must have a trade deal with the EU in place by January 1, 2021.

The chances of this would appear to be remote, especially as the talks would need to be largely completed by the end of June in order to meet this deadline, according to EU watchers.

The complexity of the negotiations and all precedent with EU trade deals suggests the timetable isn’t going to be met – it has, after all, taken three-and- a-half years to reach this point.

Mr Johnson – who has, admittedly, already twice defied expectations by securing the deal with the EU and then winning such a large majority in the election – optimistically points out that, as the UK is already aligned to EU rules, the negotiation should be straightforward.

The reality, however, is that while he wants to retain close relationships with the EU, he also wants the flexibility to diverge from EU rules in order to strike deals with other countries, which is where life will get tricky. The more divergence the UK wants, the tougher the EU’s stance.

The EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, said the extent to which the EU will agree to continue frictionless trade with the UK would depend on the how far the UK ‘wants to distance itself from the EU’s regulatory model’.

The new EU Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, said the deadline left ‘very little time’ for the sides to reach a trade agreement. “In the case we cannot conclude an agreement by the end of 2020, we will face, again, a cliff-edge situation and this would clearly harm our interests, but it will impact the UK more than us,” she said.

So, as 2020 unfolds, we could once again be facing the prospect of a looming no deal and a cliff edge switch to trading on WTO terms, with all that entails for the pig sector, particularly given the Government’s unfair and uneven approach to no deal tariffs.

In reality, it is unclear how much flexibility there will be, if needed, to extend the transition – but Mr Johnson is certainly doing all he can to give the impression there will be none.

AGRICULTURE POLICY

Meanwhile, the pre-Christmas Queen’s Speech confirmed the return of the Agriculture and Environment Bills, signalling a new direction for agriculture.

In England, that means the phasing out of direct payments – which have helped shield the wider farming sector from the vagaries of the weather and the marketplace – to be replaced with payments for public goods.

This will provide opportunities for a sector that has not historically benefited from direct payments, for example, in the form of support to help improve productivity and help deliver high welfare, health and environmental standards.

But it also part of a wider drive, potentially backed by regulation, to elevate UK standards when it comes to these areas. The fast-tracking of environmentalist Zac Goldsmith – who has campaigned alongside Defra Secretary Theresa Villiers to ‘End the Cage Age’ – into the House of Lords to enable him to retain his Defra ministerial role is a very clear sign of the direction of travel Mr Johnson envisages.

IMPORT STANDARDS

The UK will, at the same time, be seeking new trade deals beyond the EU. President Donald Trump was one of the first people to congratulate Mr Johnson on his victory, tweeting about a ‘massive new trade deal’ that now becomes possible between the US and UK.

That comes with huge risks. As has been well documented, a pre-condition from the US meat sector and Government to any trade deal is that the UK must ‘eliminate the market impediments’ currently imposed at EU level. For pork that means, for example, removing the ractopamine ban and accepting the US plant inspection system as equivalent to ours, the US National Pork Producers Council’s Nick Giordano told Pig World. That is before we even get on to fundamental welfare differences like the use of sow stalls.

Government ministers have, repeatedly, insisted they would not compromise our welfare standards in post-Brexit trade deals, but have refused to commit to any legislative measures to deliver this.

Speaking at the Young NPA National meeting in December, NFU vice-president Guy Smith warned that if the UK opens its doors to lower standard imports, while ratcheting up its own standards, it could fatally undermine large parts of the UK farming industry.

How a populist, all-powerful Mr Johnson handles the tension between striking new deals that deliver fresh sources of cheap food for voters and the need to protect the farmers he is asking to deliver higher standards, will be watched nervously within the farming community.

NPA chairman Richard Lister said Brexit offered opportunities to ‘exploit the markets wishing to buy our farm assured, high welfare British pigmeat products’, alongside the threats of ‘potentially lopsided’ WTO tariffs and a failure to protect the UK’s welfare standards. “The recognition of our standards of production will be paramount to any future trade deals,” he said.

NFU president Minette Batters reiterated her calls for a trade and standards commission to advise the Government on future trade agreements and ensure UK standards are not undermined.

“I have been clear that we must value our high farming standards and not sacrifice them in future trade deals, in favour of imports of food produced to standards that would be illegal in the UK,” she said.