Defra has confirmed plans to introduce new regulations to bring about fairer trading relationships in the pork supply chain. While its response to last year’s consultation is encouraging, the challenge now is to get the detail right. ALISTAIR DRIVER reports

The British pig sector has had its say and, to its credit, Defra has listened, something that cannot always be said to have been the case of late.

Defra’s publication of the summary of responses to its consultation on contractual practice in the pig sector, setting out its next steps, made for encouraging reading.

It has accepted the overwhelming consensus of the pig sector, and producers in particular, that there are, in Defra’s words, ‘legitimate concerns about the nature of business relationships in the UK pig sector’.

That was a polite way of putting it, as the responses to laid bare ‘a lack of trust between producers and processors’ that were particularly evident during the horrendous pig backlog, and highlighted ‘an imbalance of power’ that has proved damaging to those in the business of producing pigs, particularly in the independent sector.

The responses showed pig producers want more robust contracts, which, underpinned by legislation, deliver a fair and transparent price, with a dispute resolution in the background, if needed. They also want to see more transparency across the chain and moves to address this imbalance of power.

Having set out the case for legislation, Defra outlined the broad principles it intends to follow. The headline is a pledge to commence work developing regulations for pig contracts, using powers in section 29 of the Agriculture Act 2020. These regulations will ensure written agreements are used between all producers and their buyers.

The Department will now work closely with the industry to explore what other provisions, if any, should be mandated as part of these agreements.

It will also develop regulations to collect and disseminate more supply chain data, particularly in relation to wholesale price transparency and national slaughter numbers, using the powers under the Agriculture Act in England and working with the devolved administrations.

But the most intriguing commitment is to share its findings relating to the alleged negative consequences of market consolidation in the sector with the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA).

Defra said these new regulations would help to bring stability and security to the pig supply chain, strengthening the its ability to deal with the challenges currently being faced around the world.

Farming Minister Mark Spencer said: “The pig sector has faced unprecedented challenges over the last year, with rising costs and global labour shortages putting real pressure on producers and processors. We are committed to working with the sector, and the regulations set to be introduced will ensure fairness and transparency across the supply chain – from pig to pork to plate – to help the sector to thrive in the future.”

Expectations have to be managed – the document was short on detail and there is a long road ahead to get necessary regulation in place to deliver meaningful reform. But there is no doubt this is a positive response and something to build on.

The consultation

The hefty response to Defra’s consultation, which ran from July to October, has provided a clear mandate for the Government to act.

There were 374 submissions, considered a strong response, given the size of the industry, with 61% from independent producers, 5% from trade bodies, 3% from both marketing groups and integrated pig businesses and 1% or less from retailers, abattoirs, secondary processors, wholesalers and cooperatives. Two-thirds of the responses were from England, with Northern Ireland and Scotland making up most of the remainder.

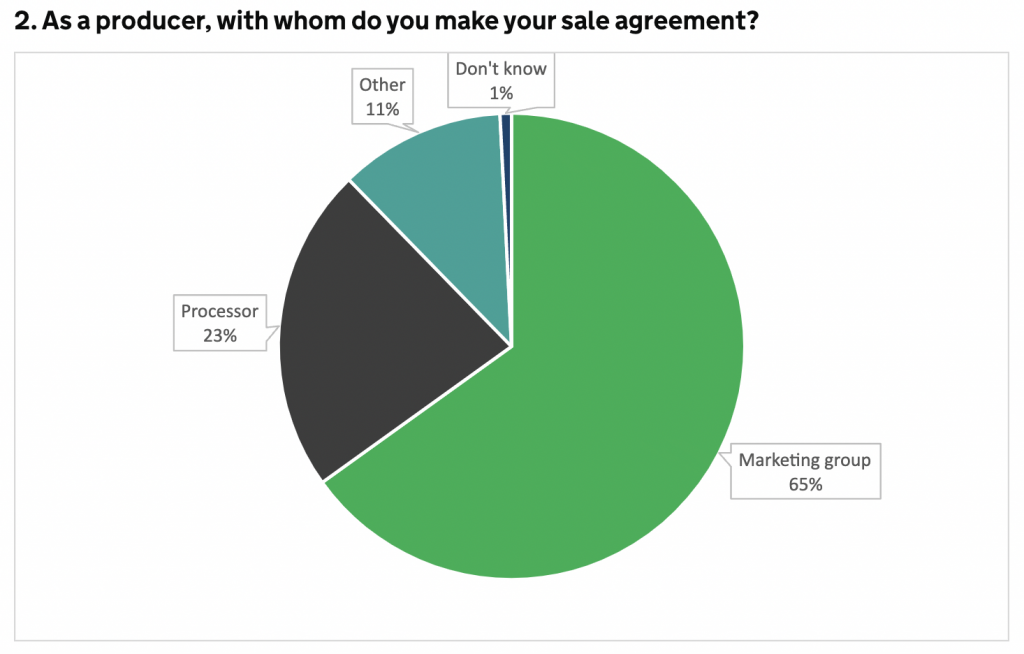

Nearly two-thirds of producers who responded to the survey sold their pigs through a marketing group, with 23% selling straight to a processor.

Pig contracts

Pig contracts

Written agreements accounted for 66% of all agreement types, although around a third of these were updated verbally, while a quarter of agreements were verbal and 10% of producers either had no formal sale agreement or did not know what type of contract they hold.

How agreements are altered varies, but one comment highlighted the often one-sided nature of relations: “Alterations to agreements are typically initiated by the processor, whether fluctuations in pig numbers or an increase in meat processing charges. These are often not open to negotiation and are imposed without the ability to contest or vary due to the size of the processor versus me as a small producer.”

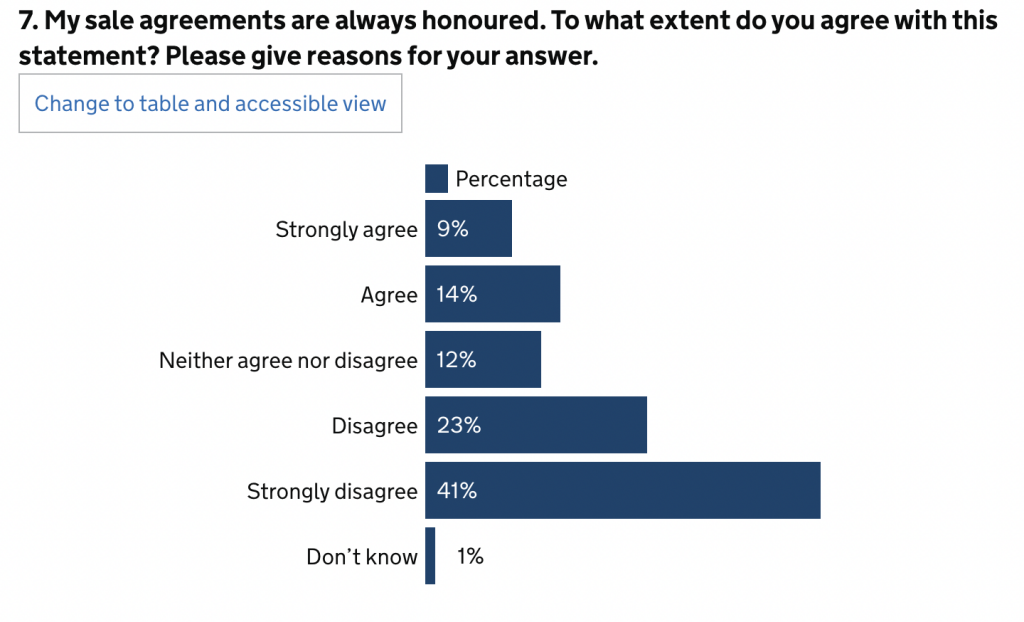

Almost half the responses indicated that processors do not honour contracted numbers and regularly ‘roll’ pigs, while one in five said pre-agreed prices are not always honoured by processors. Less than a quarter agreed with the statement: ‘My sale agreements are always honoured’, compared with nearly two-thirds who disagreed.

One in five said pre-agreed prices are not always honoured by processors, while some highlighted the imbalance of power in the supply chain and said that, unfairly, risk tends to be put on producers. Others mentioned, however, that they had good business relationships and that, overall, the system works.

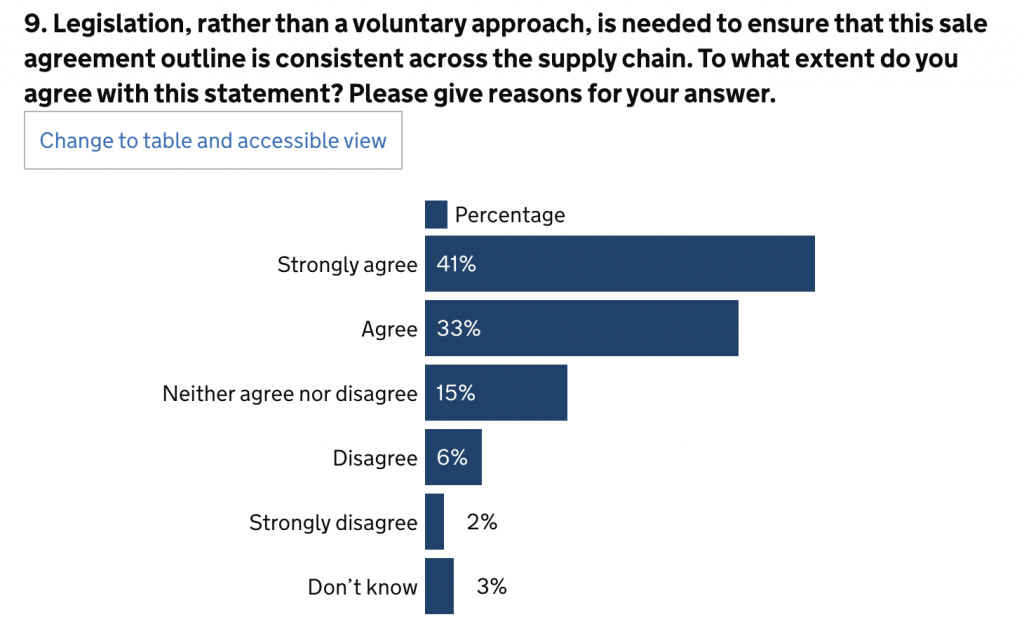

An overwhelming 89% agreed that all sale agreements between producers and purchasers should be covered by a written agreement, with three-quarters believing legislation is needed to ensure agreements are consistent across the supply chain. Others maintained, however, that the market should self-regulate, while responses from secondary processors or abattoirs were evenly split: 44% in favour of legislation and 44% against.

The Defra report stated: “There is a clear demand for a legislative solution, and evidence of a popular sentiment that legally required written contracts would remove the uncertainty and ambiguity which has underlain recent issues.”

What should contracts look like?

While the case for mandatory written agreements was clear, there was far weaker consensus regarding what they should cover and whether these agreements should be standardised throughout the sector, however.

Nearly 70% of respondents were in favour of all sale agreements following a set structure and including reference to the same terms and conditions. Some believed this would provide more security and fairness for producers and improve transparency and consistency across the industry as a whole.

Producers recognised, however, that too much contractual rigidity could have unintended consequences on the market. A common sentiment was that any regulation should allow flexibility and not be overly prescriptive, particularly where the nature and size of businesses differ.

A fifth of responses suggested that any structure should be seen as a minimum, baseline framework to allow for any market changes. Others stressed that there is no appropriate ‘one size fits all’ structure, with one noting that a ‘broad sweeping brush won’t allow for subtle differences between contracts at different locations, with regards to spec, weight, numbers, volume etc’.

In terms of specific clauses, more than half the responses, including secondary processors and abattoirs, believe the minimum number of pigs to be supplied should be included.

Several respondents felt that force majeure clauses should be mandatory in a sale agreement, but that these should be more clearly defined with specific definitions to prohibit either party from taking advantage.

Other clauses regularly mentioned included notice periods and termination, supply periods, premiums and deductions, and dispute resolution.

NPA chief policy adviser Rebecca Veale said this represented a huge opportunity to develop more robust contracts and acknowledged that a lot of discussion was needed to get it right and find the balance between sufficient protection for producers, in particular, but also the flexibility needed on both sides.

“But it is also important that real change starts to happen in parallel with this process, and we are picking up signs that processors understand they need to do things differently. Producers are reporting more engagement and sensible discussion over contracts,”

she said.

British Meat Processors Association chief executive Nick Allen said nobody had any issues with ‘the basic principle of having proper contracts’, but added that it was not possible to make a judgement on this ‘until we see the detail and exactly what they are actually planning’.

Dispute resolution

The events of the past two years have clearly highlighted the need for a dispute resolution mechanism, with some producers highlighting fears that processors may retaliate if they were to raise an issue.

But there was no consensus about the best approach, including whether it should be binding or advisory. Roughly 20% of respondents would prefer a binding approach, with approximately 10% favouring advisory. Some respondents suggested a combined approach, with the option to move from advisory to binding if a producer wishes to escalate the dispute further.

A common theme throughout responses was that any form of dispute resolution, whether binding or advisory, must be undertaken by an independent third party to ensure it has oversight of the supply chain and can be trusted by all parties to the agreement.

Some respondents stated that they would like a dispute mechanism to be an ombudsman or adjudicator, with the Groceries Code Adjudicator mentioned as a popular model.

Pig price

Many respondents use either the All Pig Price (APP), SPP or Tribune market indices. A few respondents pointed out, however, that their intended

use is not as a pricing metric and that they should not be used as such.

Of those respondents using the APP or SPP, many utilise a ‘SPP+’ price, where the SPP is supplemented by other factors, such as the processor’s shout price. It was suggested that the SPP is generally clear and easy to follow, while the processors’ own contribution is difficult to understand as it is administered with little or no detail.

Fifty-seven per cent of respondents agreed that the factors affecting price are clear, although this is not consistent across all factors affecting price, while 28% disagreed.

Many respondents would like to see more transparent and accessible cost of production figures, although there is recognition that these figures are often complex to establish and could be manipulated.

Respondents generally wished to see improved communication across the supply chain to enable a better understanding of pricing factors.

While more than half of respondents believe that premiums and deductions are clear, some said premiums are often more ambiguous and often not passed on to the producer. Many highlighted deductions for overweight pigs during the backlog where abattoirs failed to take pigs on the pre-agreed dates.

When it came to contracts, more than a quarter of responses mention the inclusion of a price or pricing structure.

There were also calls to link cost of production more closely to the price. Indeed, we are already seeing changes within the industry in terms of how price is set, including more contracts being linked to cost of production.

There is a desire among some within the sector to see the SPP expanded to incorporate more pig types, showing information about processor-owned pigs, outdoor-reared pigs and organic pigs, generating more reflective price for the entire UK market.

Independent industry analyst Mick Sloyan said the SPP could be replaced with a price that reflected the average price for all pigs sold either in GB or UK.

The SPP or Standard Pig Price excludes ‘premium’ pigs because contributing abattoirs participating on a voluntary basis made this a condition of their continued cooperation, he wrote in the Weekly Tribune.

AHDB produces the APP to cover the whole market, but as this data is collected from pig sellers it takes a further week to publish. But Mr Sloyan said ‘life has moved on’ since and the UK now has mandatory price reporting, where all abattoirs killing more than 500 pigs a week are required to report price and throughput data each week. “It would be relatively straightforward to calculate an additional average price that covered the whole market each week,” he said.

Reporting and transparency

Half of respondents do not believe existing marketing reporting is transparent, which was consistent across responses from independent producers. Responses from marketing groups and representative organisation were less decisive.

Many responses noted that existing reports, while easy to access and understand, are voluntary and so do not cover the whole pig market and can also be skewed to deliberately generate a lower price point.

There were also concerns that existing price reporting can be easily manipulated by processors through contract structures and influencing the ‘basket’ of pigs included in such schemes.

Sixty per cent of respondents wanted access to additional data points from the first part of the supply chain – such as an expanded and more transparent SPP, total UK slaughter numbers, including a split between independent and integrated pigs and cost of production data, from producer to processor.

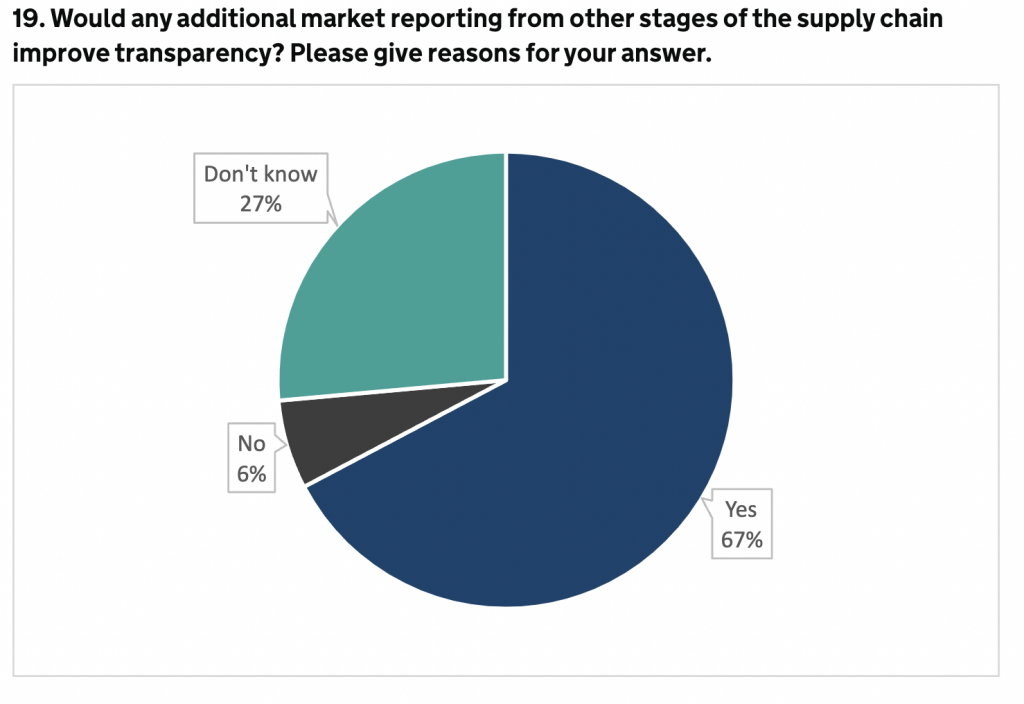

Two-thirds of respondents would like to capture additional data points from the rest of the pig supply chain, with some requesting better wholesale information, including the comparison of UK pork versus imported product.

Ms Veale pointed out that while, in terms of contracts, Defra’s powers are limited to processors, the data-gathering powers of the Act apply across the whole supply chain.

“Price reporting needs to be more transparent,” she said. “The industry will now have to think very carefully about exactly what data we want, how to collect it and what that would look like in practical terms.”

But Mr Allen said the processing sector was ‘baffled’ over Defra’s comments on wholesale price transparency and was seeking clarification.

“There is really no wholesale market and, once it reaches the processor, pork doesn’t change hands until the supermarket. Do they mean the supermarket price?” he said.

Mr Sloyan pointed out, however, that the US, which has a highly concentrated and integrated pork supply chain, does report wholesale pork prices in the form of a comprehensive market report each week covering carcase, primal and sub-primal prices.

He said this should be feasible in the UK and would ‘improve transparency and provide a factual basis for discussions about the impact of EU prices on the UK market’.

Consolidation

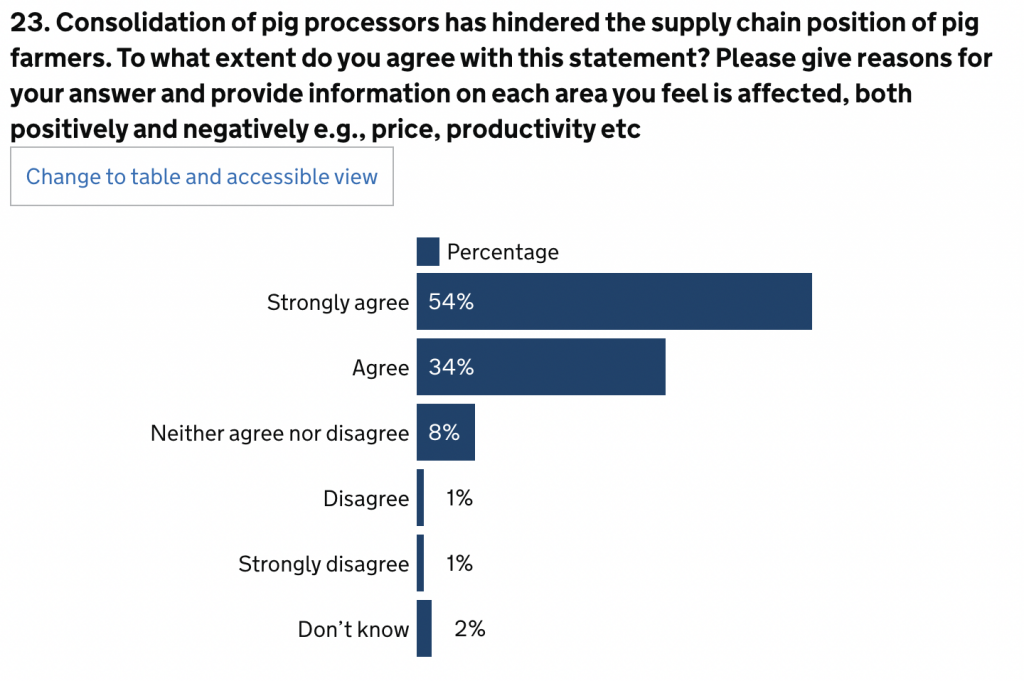

An overwhelming 88% of respondents believe that processor consolidation has hindered the position of farmers, with many attributing low pig prices to a lack of market competition as the reduced number of processors forces producers to be price-takers.

“Control in so few hands is not healthy. Many, many small outlets have disappeared and choice of market for farmers is seriously limited because of this,” one said.

Some respondents noted that the effects of consolidation are worse for independent producers. “Processors have their own pigs now and will look after them first,” one said.

There was also a consensus that consolidation has limited the ability of pig farmers to specialise.

It remains to be seen what the CMA makes of the information passed to it by Defra and whether it feels it has sufficient grounds to act. Either way, the statement should certainly make the whole chain sit up and take notice.

Mr Sloyan said: “It is clear that the CMA can and does work very quickly and decisively where they believe there are unfair trading practices. The whole supply chain will be watching and waiting for the CMA opinion.”

Contingency planning

Responses suggest that there is an inherent unfairness in the imbalance of contingency requirements between producers and processors.

Respondents suggest that all responsibility for dealing with unforeseen circumstances, and associated financial risk, is unfairly placed with producers.

What happens next?

The regulations will be developed using the regulation-making power in section 29 of the Agriculture Act 2020, with, Defra said, further engagement with industry first to ensure they meet the needs of the sector and properly address the challenges it faces.

In other words, there is plenty more discussion to be had before it gets written into legislation, so nothing will happen quickly. The devil will very much be in the detail and with such a wide range of views on how contracts should look and prices set, alongside question over the data side of things, this will require some detailed engagement.

Ms Veale said the NPA would meet Defra ‘frequently’ to discuss policy development. She also welcomed the fact that the Department is putting more resource into the team working on it.

“However, we can’t get away from the reality that the Department’s resources are going to be stretched, particularly as it grapples with the vast Retained EU Law Bill, and we might also have to factor in a General Election next year. We would love to get this through in 12 to 18 months, but, realistically, even that might be an ambitious timeframe. It is dependent on lots of factors.

“Ultimately, it is about having a piece of legislation that is fit for purpose. We do not want to push for something quickly if that means it will be sub-standard. This is a pivotal moment; we are not going to have another opportunity like it. It is going to shape the industry for the long-term, so we have to get it right.”