Major pork producing nations are being urged rethink their long-term market strategies, as rapid Chinese herd expansion suggests the Asian export boom is peaking. Alistair Driver reports

Asia’s African swine fever (ASF) crisis, while disastrous for those on the frontline, has helped underpin the global pork market for the past two years.

This year, in particular, strong Asian export demand has been ‘extraordinarily helpful’ to pig producers worldwide, helping to offset the COVID-19 disruption that has hit plants and weakened domestic and export demand in some places, according to Rabobank.

Global pork demand has rebounded following COVID-19 disruption, yet supply remains constrained in many Asian markets, which continues to support strong export demand, resulting in ‘sharply higher pork values’, the Dutch food industry banking specialist said in its latest quarterly pork report.

But the Chinese export boom could soon be ending as the rebuilding and reshaping of China’s pig herd continues apace. This could have a profound effect on pork producers that have been growing production to satisfy China’s needs, Rabobank said.

Meanwhile, in Europe, Germany’s ASF outbreak could have a lasting effect beyond its borders.

Chinese import growth

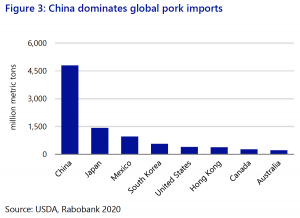

China now accounts for more than 40% of global pork imports (Fig 3), following dramatic growth this year to fill the hole left by the ASF outbreak, which, discovered in August 2018, is estimated to have halved China’s 700 million pig population in 2019.

Fig3  China imported 3.7m tonnes of pork, including offal, in the first eight months of 2020, double 2019 levels, while total imports for the year are expected to reach 4.8m to 5mt.

China imported 3.7m tonnes of pork, including offal, in the first eight months of 2020, double 2019 levels, while total imports for the year are expected to reach 4.8m to 5mt.

However, the pace of imports is expected to slow for the remainder of the year, partly due to China’s strict stance on COVID-19. Customs officials have strengthened port inspections and suspended a number of export licences.

In the first four months of 2020, the US was the top exporter to China, after a thawing of the China-US trade dispute; followed by Spain, Germany, Brazil and Denmark.

The UK was tenth on the list, with Chinese export volumes growing by 51% year-on-year over the first eight months of this year to 120,000t, representing 45% of total UK pork exports over the period.

The benefit to the UK pork processors, including for carcase balance, cannot be overstated. Cranswick’s profits for the last financial year topped £100m as export revenue almost doubled on the back of soaring Far East sales.

Impact of German ASF outbreak

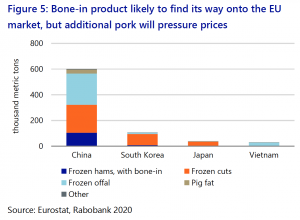

Germany’s ASF outbreak is shifting the EU dynamic. At least 10 countries have banned German pork, including China, South Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, which between them represented three-quarters of its non-EU pork exports in 2019.

Germany exported 200,000t of pork to China in the first quarter of 2020 alone, and its Chinese exports were worth around €1 billion (about £900m) annually.

German pig prices fell sharply after the virus was discovered in wild boar in Brandenburg in September, standing at 13% below pre-ASF levels. While Rabobank predicts the control measures put in place will prevent the virus reaching the domestic pig population, it forecasts ‘prolonged market disruption’ for German producers.

Rabobank suggested exporters in Spain, Denmark, and the Netherlands would be the most likely to benefit from partially filling the export gaps. But, overall, EU trade is heavily disrupted, with about 75,000t of pork that would otherwise have been exported requiring an alternative market each month, primarily in the EU, where regionalisation means exports from outside the infected areas are still permitted (see Fig 5).

Increasing exports to Denmark and the Netherlands are an option due to the strong presence of Danish Crown and VION in Germany, but the trade is limited due to issues on both the retail and – due to COVID-19 – foodservice side. Limited EU freezer capacity will constrain processors’ ability to put pork into storage to prevent congestion at the farm level.

Increasing exports to Denmark and the Netherlands are an option due to the strong presence of Danish Crown and VION in Germany, but the trade is limited due to issues on both the retail and – due to COVID-19 – foodservice side. Limited EU freezer capacity will constrain processors’ ability to put pork into storage to prevent congestion at the farm level.

With limited export alternatives and ‘strained domestic demand’, there is likely to be further oversupply of pork in the German and EU markets.

“If China does not accept the EU regionalisation policy this year, that would imply a prolonged period of sustained low prices, which will likely accelerate farm exits in Germany,” Rabobank said, pointing to low piglet prices, 27% below pre-ASF levels, as evidence of a reluctance to restock at farm level.

Even if China accepts German regionalisation, EU pig prices are unlikely to return to 2019 highs, as China’s import demand is expected to gradually soften, it added.

Rebuilding the herd

Indeed, an even more significant long-term trend is the rate at which China is rebuilding its pig herd.

It began restocking its farms in late-2019 and is now firmly on the road to replacing its once dominant backyard pig production with state-of-the-art, biosecure facilities.

“China is ramping up imports of its breeding stock and making sizeable investments in its genetic base, reaffirming our view that it is now able to manage any future ASF outbreaks and limit additional herd losses,” Rabobank added.

The Chinese government intends to become largely self-sufficient in pork and Rabobank believes China could return to 95% self-sufficiency as soon as 2024/25, with import volumes set to fall gradually.

“This provides a window of continued opportunity for global pork exporters to see incremental demand increases, but this window is likely to close in the coming years,” it said.

The Government has been proactive in supporting herd expansion, through for example, grants, local planning policies and measures to keep ASF at bay and improve industry biosecurity. This has come on top of the increased import levels and releasing stocks from storage to ease the pressure of its pork shortage.

It appears to be working. Live pig prices fell in September and China’s agriculture ministry recently announced that, with pork supplies continuing to improve, the damaging price fluctuations of the last two years are likely to stabilise for the rest of the year.

Rabobank estimates that the Chinese breeding herd is currently 15% above its lowest levels and will continue to expand.

Pig production is expected to turn positive in the current quarter, reversing the negative growth experienced so far this year and in 2019. It expects a further acceleration in 2021, although the pace of growth will depend heavily on continued control of ASF over the winter.

China recently confirmed its first outbreak since July, but Rabobank believes any future impact will be ‘significantly smaller’ than that experienced in 2018/19.

It estimates, therefore that Chinese pork production in 2021 will increase by more than 10% on 2020, resulting in a 20% to 30% drop in pork imports, about 1m tonnes, over the year.

“To put this in perspective, a drop of this magnitude equals about 10% of global pork trade. With five countries responsible for 85% of total pork imports annually, it may be increasingly difficult to redistribute the pork no longer needed by China,” the report said.

Christine McCracken, senior analyst – animal protein at Rabobank, said: “Chinese pork production is expected to normalise by 2024, which will leave a global supply overhang.”

A challenging time?

The massive herd losses seen in China and South East Asia sent a signal to producers around the world to grow production, which has increased in countries outside the ASF-affected regions by 4.8%, with the US, in particular, proactively growing its herd.

But the drop in Chinese demand is now likely to force many exporting nations to refocus efforts on secondary trade markets and, ultimately, result in larger domestic supplies.

“This is likely to translate into weaker product pricing and lower hog values,” Rabobank said. The challenge is how to offset the expected decline in Chinese demand with a combination of larger exports into alternative destinations and accelerating domestic demand growth, while also slowing the growth in supply.

“With export growth more limited in the next few years, due to a slowing economic outlook, this may be more challenging.

“Ultimately, though, we believe it will result in a less robust production pipeline and a smaller sow base in countries outside those impacted by ASF in recent years.”

For the UK, there is no doubt China will continue to be a lucrative market in the short and medium term. But Rabobank’s assessment certainly delivers food for thought.