The positive producer margins of 2017 have all but disappeared as input costs rise, reaching a four-year high recently. In the wake of the summer drought, further input hikes are expected. Alistair Driver looked at the situation in the September issue of Pig World

‘Bacon Butty Crisis!’ a Daily Star front page screamed last week, explaining how the summer ‘Sizzler’ has hit pigs’ fertility’.

There was a similar story in The Sun, while the rest of the media was full of slightly more restrained stories about rising food prices on the back of this year’s extreme weather. It was all based on research by consultancy CEBR predicting that meat, vegetable and dairy prices are set to rise by ‘at least 5%’ in the coming months, adding more than £7 toconsumers’ monthly food bills.

Some product prices have already soared since the spring (March to July), including onions (+41%), carrots (+80%), lettuce (+61%) and milling wheat (+20%). Butter prices are up as dairy production registered 11 consecutive drought-hit weekly falls, while feed and straw supplies were further depleted, adding to costs across the livestock sectors.

CEBR also highlighted the impact of the heatwave on pig fertility, hence the ‘bacon butty’ headlines. The effect of the heat on semen quality and heat stress in sows, largely an issue for outdoor sows, will not be seen for a few months yet, but NPA chief executive Zoe Davies stressed that producers were not predicting a major impact. And given that a large percentage of our bacon is imported from the EU anyway, we unlikely to see a bacon butty shortage, she added. Panic over.

Nonetheless, the message to consumers that their food is getting more expensive, needed some context, which was provided by NFU statistician Anand Dossa. He pointed out that, even with the increase, food prices will still be historically low – they currently account for just 8.2% of UK household expenditure, compared with 30% in the 1950s.

And, as AHDB’s Phil Bicknell also highlighted, food’s 1.4% price increase since 2015 is dwarfed by other consumer cost rises, notably electricity (+16.7%), travel fares (+19.8%) and fuel (+14.7%).

The harsh reality, in fact, for farming generally, and certainly the pig sector, is that input costs are currently rising faster than farmgate prices.

Pig production costs

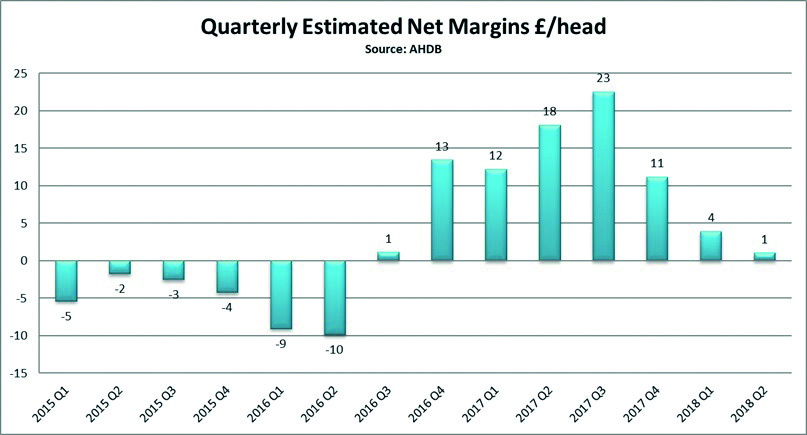

Pig production costs reached a four-year high of 150p/kg during the second quarter of 2018, virtually eroding the positive margins enjoyed in 2017, according to analysis published by AHDB Pork.

With the EU-spec APP averaging 151p/kg during the quarter, margins averaged just 1p/kg, equating to around £1/head. This was down from £4/head in the first quarter and compared with £18/head in the second quarter of 2017 and a high of £23/head in the third.

Compared to the second quarter of 2017, production costs have risen by almost 9p/kg, while pig prices have fallen by 12p/kg. But the change between the first and second quarters of 2018 entirely reflects higher production costs (+5p/kg), as pig prices have actually increased slightly (+2p/kg), said AHDB analyst Bethan Wilkins.

“In more recent weeks, both spot and forward prices for key commodities in pig feed have further increased meaning feed costs have probably increased further,” she added.

Difficult harvest

The lack of rain, particularly when growers really needed in late June, has hit 2018 harvest yields across the UK and Europe.

According to ADAS Harvest reports in mid-August, with the wheat harvest 80% complete, GB yields were estimated at 7.7-8.0t/ha, below the five-year average (8.2t/ha), although average winter barley yields, estimated at between 6.8-7.0t/ha, were in line with the five-year average.

With the planted area of wheat 2% down on last year, AHDB’s estimated 2018 wheat yield of 13.9Mt would be 0.9Mt lower than in 2017, with 2017/18 ending stocks also forecast to be the lowest since 2013/14.

Meanwhile, feed usage data released by AHDB and Defra show that grain inclusion in animal feed increased in 2017/18, including a 3.4% growth in pig feed production. With the prolonged dry spell increasing current forage usage, and putting pressure on winter supplies, cereal demand is likely to remain high in 2018/19, AHDB said.

It is a similar story across Europe, with German grain production, for example, expected to hit a 24-year low. In its latest report the USDA has slashed its estimates of world wheat supplies and stocks, driven by the weather challenges seen globally, but primarily on lower EU production, forecast to be at the lowest level since 2012/13.

European wheat futures are currently trading around 30% higher than at the end of April.

AHDB figures highlight how cereal and protein prices have risen.

| Grains | Aug 16 | July 19 | Change |

| Ex-farm UK wheat(£/tonne) | 178.00 | 161.20 | +16.80 |

| Ex-farm UK feed barley (£/t) | 166.80 | 139.70 | +27.10 |

| Proteins | Aug 17 | July 20 | |

| Chicago soybean (Nov 18), $/t | 383.75 | 317.71 | +10.29 |

| UK delivered rapeseed (Erith, Sept) | 337.50 | 318.50 | +19 |

Ms Wilkins added: “It seems likely feed prices will remain above levels in recent years in the coming months, given some challenges to harvest yields across Europe. It is difficult to anticipate much uplift in the pig price, given increasing global production levels.

“Though with volatile global market conditions (ASF in China, trade war), there is some uncertainty surrounding the market outlook. As average producer margins were already extremely narrow, it seems probable that losses on a full costings basis may be a feature of the pig market in the coming months.”

The tougher times ahead follow two years of profitable pig production, while producers have ‘theoretically been in the black almost 60% of the time over the past decade’. “This highlights the importance of careful forward planning in pig production, enabling producers to weather more difficult periods,” she said.

Other inputs

It is not just feed prices that are rising. Higher fuel prices in July, for example, were blamed on pushing up the rate of inflation for the first time this year. Figures from the NFU’s State of the Farming Economy briefing show 2018’s weather events, combined with weak pound, saw farming input costs rise overall by 6% between June 2017 and June 2018. This included:

- Fertilisers +23%

- Motor fuel +20%

- Soya bean meal +16%

- Energy and lubricants +16%

- Feed barley +7%

- Electricity +7%

- Heating fuel +6%

- Feed wheat +5%

But there will, hopefully, be some relief for pig farmers, however, as the 2018 harvest saw plenty of straw baled, as farmers have responded to the recent shortages and higher prices, helped, of course by the dry weather, in contrast to the wet late-summer and autumn of 2017.

“Straw is looking more plentiful and prices are starting to reflect this,” the British Hay & Straw Merchants Association.

Higher input costs equate to worrying times – NPA chair

NPA chairman Richard Lister said rising input costs equate to ‘worrying times’ for UK pig producers.

NPA chairman Richard Lister said rising input costs equate to ‘worrying times’ for UK pig producers.

His farm mixes two-thirds of its feed for its indoor units in Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire. “We have really seen the wheat price gather some momentum since the harvest. Pre-harvest, we were paying £150 tonne for wheat but we have seen it go to £190/t for November, although it’s come back a bit. It tends to have a bit of drag effect on all the other raw materials

With cereals making up at least 50% of the cost of feed, he said it was inevitable that feed prices would rise further over the next six months.

“Anybody who bought six months ago for a year ahead will have some relief, but people who haven’t taken forward cover will be facing some nasty rises,” he said.

Mr Lister added that his latest quote for electricity on one of his sites was 23% up last year, although he noted that straw sheds around the country were ‘brimming’, which should bring relief to some farmers.

“But the feed price situation, in particular, is cause for concern because when those prices come through, it will push people into negative margins,” he added. “Pig prices have been relatively stable, although there are lots of variables looking ahead, for example, African swine fever in China could potentially boost the market.

“But one of the big problems is the uncertainty around Brexit, which is not helping trade and is stifling investment. Processors are not very buoyant on pricing and putting money back into people’s pockets. A Brexit no deal, in particular, could also push costs up further if imports become more expensive.”

“The overall outlook is worrying and we will need strong support in the marketplace.”